Author Archives: Bhakta Chris, New York, USA

Why This Devotee of God Doesn’t Think To Be Atheist Is To Be A Demon

Why This Devotee of God Doesn’t Think To Be Atheist Is To Be A Demon

→ Life Comes From Life

When Saying "It’s Just Kali-Yuga" Is Not Enough

→ Life Comes From Life

“True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

When Saying "It’s Just Kali-Yuga" Is Not Enough

→ Life Comes From Life

“True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

When Saying "You Are Not Your Body" Is Not Enough

→ Life Comes From Life

When Saying "You Are Not Your Body" Is Not Enough

→ Life Comes From Life

Loving Ourselves, Part 1

→ Life Comes From Life

Loving Ourselves, Part 1

→ Life Comes From Life

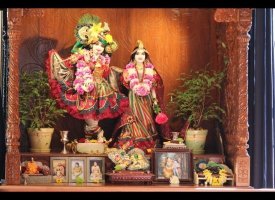

Guides, Gurus and Grounding In Our Spiritual Journey

→ Life Comes From Life

My latest from The Huffington Post Religion Today is Guru Purnima, and this spiritual festival takes on a very special resonance for me this year. Just a few weeks ago, I was formally initiated into the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition at a ceremony…

Guides, Gurus and Grounding In Our Spiritual Journey

→ Life Comes From Life

My latest from The Huffington Post Religion Today is Guru Purnima, and this spiritual festival takes on a very special resonance for me this year. Just a few weeks ago, I was formally initiated into the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition at a ceremony…

The Barking Dog of The False Ego

→ Life Comes From Life

My latest essay at The Huffington Post Religion Our ego is one of the most intimidating and inscrutable realities we face in our lives. Countless philosophers, spiritualists, seekers and armchair prognosticators have tried to define its paramet…

The Barking Dog of The False Ego

→ Life Comes From Life

My latest essay at The Huffington Post Religion Our ego is one of the most intimidating and inscrutable realities we face in our lives. Countless philosophers, spiritualists, seekers and armchair prognosticators have tried to define its paramet…

Homosexuality And Scripture

→ Life Comes From Life

Homosexuality And Scripture

→ Life Comes From Life

A Case For Celibacy, Sobriety & Sanity.

→ Life Comes From Life

Read the full version of my new article at Elephant Journal

I choose not to have sex unless my intention would be to produce a child with my wife. In all other circumstances, I strive for a complete and healthy celibacy. I choose not to take any intoxicants, not alcohol or marijuana, or even tobacco or caffeine. I choose not to gamble, to speculate whatever finances or assets I may have. I choose not to eat any meat, fish, or eggs. I’ve been a committed vegetarian for over seven years now, and I’ve even flirted with veganism on occasion as well.

You may think I’m crazy, fanatical and hopelessly out-of-touch with the natural pleasures of the body and mind that seem to be our birthrights. As a practitioner of the bhakti-yoga tradition, my community, my teachers, and my calling ask of me a commitment beyond the normal, expected and comfortable.

It certainly isn’t easy to follow these regulative principles, but by doing so, I can understand what it means to be a human being and spiritual being and all that combination entails in today’s over-driven and over-stimulated world.

A Case For Celibacy, Sobriety & Sanity.

→ Life Comes From Life

Read the full version of my new article at Elephant Journal

I choose not to have sex unless my intention would be to produce a child with my wife. In all other circumstances, I strive for a complete and healthy celibacy. I choose not to take any intoxicants, not alcohol or marijuana, or even tobacco or caffeine. I choose not to gamble, to speculate whatever finances or assets I may have. I choose not to eat any meat, fish, or eggs. I’ve been a committed vegetarian for over seven years now, and I’ve even flirted with veganism on occasion as well.

You may think I’m crazy, fanatical and hopelessly out-of-touch with the natural pleasures of the body and mind that seem to be our birthrights. As a practitioner of the bhakti-yoga tradition, my community, my teachers, and my calling ask of me a commitment beyond the normal, expected and comfortable.

It certainly isn’t easy to follow these regulative principles, but by doing so, I can understand what it means to be a human being and spiritual being and all that combination entails in today’s over-driven and over-stimulated world.

A Hindu Response to Gay Rights

→ Life Comes From Life

From the Religion section at The Huffington Post

I was personally very impressed and moved by President Obama’s decision to come out openly and vocally in support of same-sex marriage. For all the guff we throw at him, and not withstanding the obvious political calculations that came along with the decision, his move was a courageous and truly historic gesture befitting the expectations that came along with his ascendancy to the presidency.

The cultural waters in terms of gay rights continue to move and shift in profound and irreversible ways.

I see this as well in the religious communities that I am part of. Recently, my friend Bowie Snodgrass, who is one of the executive directors of the excellent Interfaith community Faith House here in Manhattan, presented a sampling of the liturgy, song, and scripture she and others in the Episcopal Church have been developing for a same-gender blessings marriage ceremony. (For more information, click here to visit the Episcopal Church’s “Same-Gender Blessings Project”)

Still, within my own tradition (the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition of Hinduism), and within its contemporary cultural expressions, I feel a certain hesitancy to be so supportive of gay rights. Within my own heart and conviction, there is no conflict. But I wonder how I will be perceived by my immediate and extended religious community. Nevertheless, I use this platform on The Huffington Post to bring this conflict into a brighter light, because I think it is part of the larger question of establishing and defining the relevancy of my tradition in the world today.

It is an unfortunate aspect of my experience within the Vaisnava tradition that I have experienced prejudice towards the gay community. Some of this prejudice has been overt, some of it simply a matter of cultural conditioning and unfamiliarity, but in either case, it has always made me quite uncomfortable. I had many gay and lesbian friends when I was an undergrad at the University of Michigan. I imagine I will have many gay and lesbian friends when I began grad school at Union Theological Seminary in the fall. I am naturally comfortable with people of this sexual persuasion, because of the simple fact that, beyond sexual preference, I see no difference between them and me.

Therefore when I encounter prejudice against gay people and gay culture, even if it is not with the intent of malice, it feels abhorrent in the fiber of my being and spirituality.

I feel comforted knowing there are many people of faith who feel the same way I do, and who are trying to come to grips and understand why the prejudice of homophobia can never be supported in any kind of genuine spiritual way. As always, I look to support from the timeless scriptures of the Vedas, the fount of universal wisdom. For example, in the Bhagavad-Gita, Krishna states:

The humble sages, by virtue of true knowledge, see with equal vision a learned and gentle brāhmaṇa, a cow, an elephant, a dog and a dog-eater (outcaste).

From this passage we understand a very elevated spiritual principle that calls out to our everyday experience. The fact of the matter is that prejudice of any kind has no spiritual foundation. We are called as spiritual people to apply the principles of equality, and to understand how these principles of equality can be applied in the secular world in a common-sense way, so that people do not unnecessarily suffer because of who they are, and so they can be encouraged to understand their real spiritual nature, beyond any conceptions of the physical body.

One may make an argument that gay marriage is not supported by scripture or tradition, but is homophobia ever supported by scripture or tradition? Forgive my ignorance per se if this kind of prejudicial support exists, but even within the scriptural evidence of Hindu antiquity there is plenty to support a nuanced and inclusive culture towards people of same-sex persuasion. To explore such an example, I suggest taking some time to read an excerpt from the book “Tritiya-Prakriti: People of the Third Sex-Understanding Homosexuality, Transgender Identity and Intersex Conditions Through Hinduism” by Amara Das Wilhelm, which is available at the website of GALVA (The Gay And Lesbian Vaisnava Association).

In his book, Wilhelm explores the reality of the “third sex” (tritiya-prakriti) and its various permutations as we know them today in the LGBTQ community. He reveals how individuals of the “third sex” naturally fit into traditional Hindu/Vedic culture, and how they were not excluded from traditional social customs like marriage and religious customs as well. It was an enlightening read for me, and I imagine it might be for you as well.

In future editions of this blog, I want to continue to explore the issue of prejudice against the LGBTQ community within my own tradition, and how these issues relate to and expand outwards within the spiritual quilt of our humanity. I do no want to shy away from this conflict as I see it, even if it brings upon me misunderstandings and doubts from others.

Follow Chris Fici on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@ChrisFici

A Hindu Response to Gay Rights

→ Life Comes From Life

From the Religion section at The Huffington Post

I was personally very impressed and moved by President Obama’s decision to come out openly and vocally in support of same-sex marriage. For all the guff we throw at him, and not withstanding the obvious political calculations that came along with the decision, his move was a courageous and truly historic gesture befitting the expectations that came along with his ascendancy to the presidency.

The cultural waters in terms of gay rights continue to move and shift in profound and irreversible ways.

I see this as well in the religious communities that I am part of. Recently, my friend Bowie Snodgrass, who is one of the executive directors of the excellent Interfaith community Faith House here in Manhattan, presented a sampling of the liturgy, song, and scripture she and others in the Episcopal Church have been developing for a same-gender blessings marriage ceremony. (For more information, click here to visit the Episcopal Church’s “Same-Gender Blessings Project”)

Still, within my own tradition (the Gaudiya Vaisnava tradition of Hinduism), and within its contemporary cultural expressions, I feel a certain hesitancy to be so supportive of gay rights. Within my own heart and conviction, there is no conflict. But I wonder how I will be perceived by my immediate and extended religious community. Nevertheless, I use this platform on The Huffington Post to bring this conflict into a brighter light, because I think it is part of the larger question of establishing and defining the relevancy of my tradition in the world today.

It is an unfortunate aspect of my experience within the Vaisnava tradition that I have experienced prejudice towards the gay community. Some of this prejudice has been overt, some of it simply a matter of cultural conditioning and unfamiliarity, but in either case, it has always made me quite uncomfortable. I had many gay and lesbian friends when I was an undergrad at the University of Michigan. I imagine I will have many gay and lesbian friends when I began grad school at Union Theological Seminary in the fall. I am naturally comfortable with people of this sexual persuasion, because of the simple fact that, beyond sexual preference, I see no difference between them and me.

Therefore when I encounter prejudice against gay people and gay culture, even if it is not with the intent of malice, it feels abhorrent in the fiber of my being and spirituality.

I feel comforted knowing there are many people of faith who feel the same way I do, and who are trying to come to grips and understand why the prejudice of homophobia can never be supported in any kind of genuine spiritual way. As always, I look to support from the timeless scriptures of the Vedas, the fount of universal wisdom. For example, in the Bhagavad-Gita, Krishna states:

The humble sages, by virtue of true knowledge, see with equal vision a learned and gentle brāhmaṇa, a cow, an elephant, a dog and a dog-eater (outcaste).

From this passage we understand a very elevated spiritual principle that calls out to our everyday experience. The fact of the matter is that prejudice of any kind has no spiritual foundation. We are called as spiritual people to apply the principles of equality, and to understand how these principles of equality can be applied in the secular world in a common-sense way, so that people do not unnecessarily suffer because of who they are, and so they can be encouraged to understand their real spiritual nature, beyond any conceptions of the physical body.

One may make an argument that gay marriage is not supported by scripture or tradition, but is homophobia ever supported by scripture or tradition? Forgive my ignorance per se if this kind of prejudicial support exists, but even within the scriptural evidence of Hindu antiquity there is plenty to support a nuanced and inclusive culture towards people of same-sex persuasion. To explore such an example, I suggest taking some time to read an excerpt from the book “Tritiya-Prakriti: People of the Third Sex-Understanding Homosexuality, Transgender Identity and Intersex Conditions Through Hinduism” by Amara Das Wilhelm, which is available at the website of GALVA (The Gay And Lesbian Vaisnava Association).

In his book, Wilhelm explores the reality of the “third sex” (tritiya-prakriti) and its various permutations as we know them today in the LGBTQ community. He reveals how individuals of the “third sex” naturally fit into traditional Hindu/Vedic culture, and how they were not excluded from traditional social customs like marriage and religious customs as well. It was an enlightening read for me, and I imagine it might be for you as well.

In future editions of this blog, I want to continue to explore the issue of prejudice against the LGBTQ community within my own tradition, and how these issues relate to and expand outwards within the spiritual quilt of our humanity. I do no want to shy away from this conflict as I see it, even if it brings upon me misunderstandings and doubts from others.

Follow Chris Fici on Twitter: www.twitter.com/@ChrisFici

IChant: The Ultimate App

→ Life Comes From Life

From Elephant Journal

Genius is a multifaceted jewel. It has many rough edges, and it doesn’t care for any mundane norms or compromises.

The package that genius is wrapped in doesn’t necessarily belie what is within but it is the duty of time to reveal that this genius— in whatever forms it takes—speaks to our body, mind and soul in many profound and challenging ways.

I think Steve Jobs was a genius. Of course the nature of Jobs’s character and his integrity as a person are quite complicated. History will see him as the “poster boy” for the troubled, difficult persona of the genius. History will also reveal that, as he expressed it to his biographer Walter Isaacson, his feeling that he follows in a line of innovators that includes Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein, was not mere hyperbole. His influence on our cultural expressions, on our connectivity and communication, and in the ways we define ourselves as biological beings in an increasingly technological world is already immense and will only grow more so.

Being a spiritual seeker, my obligation is to see the glass more than half-full when I examine the nature of such a complex and powerful personality. The Bhagavad Gita tells us that the truly wise person sees everyone on a spiritual level, beyond the body-mind construct which is the general source of all our foibles and follies. While being very clear and honest about the dark side of Steve Jobs, still I can’t help but appreciate the honest sincerity of his ambition, his own spiritual leanings and his desire to create a legacy of ideas and products that speaks to the best of human creativity at the intersection of technology and aesthetics.

What particularly strikes me about him was his attitude towards design. An early slogan of Apple was that “simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” This mirrors a saying from my own Hindu tradition, echoed by such great teachers as Mahatma Gandhi and bhakti-yoga pioneer A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, of “simple living and high thinking.” The idea is that only when we simplify, when we clear away the dust that only complicates the obvious truth, will we be able to discover the presence of enlightenment within ourselves and all around us.

In Walter Isaacson’s excellent Jobs biography, Jonny Ive—Jobs’s confidante and core designer during Apple’s incredible renaissance of the last decade— shares his take on this philosophy of simplicity:

Why do we assume simple is good?….Simplicity isn’t just a visual style. It’s not just minimalism or the absence of clutter. It involves digging through the depth of complexity. To be truly simple you have to go really deep.

We now reap the benefits of this philosophy in so many interesting ways in our lives. Our personal computers, tablets, phones and our whole conscious existence are full of these little apps that connect us and push us and inform us in ways that deftly ride along the balance of aesthetic and technology that so inspired Jobs’s overall vision.

What exactly is an app? To put it roughly, it is a little program which shapes our daily life in a particular way. We can just see it for what it apparently is, a bit of cutting-edge technology. But I want to go a little bit further, into the depth of complexity, to shine a different light of definition on this whole idea of the app.

Disclaimer: Reading the bio of Jobs and also being the recent purchaser of a wonderful, sturdy, fast and sleek Macbook Pro, I have the inklings of having become an Apple cultist. Some of the feelings are not entirely dissimilar to my spiritual practice, for both give one the sense of a particular worldview. That is why, as I was walking through New York City recently, meditating on my prayer beads, I was struck by the idea that the mantra I was chanting was also like an app and how it was the best app I had in my life.

My spiritual practice revolves around the chanting of the maha-mantra, which is part of the Bhakti (devotional) path of Hinduism. The mantra features three names of the Divine, of God, as known in the Bhakti tradition: Krishna (the masculine aspect of the Divine), Hare (the feminine aspect of the Divine), and Rama (the pleasure reservoir of the Divine). The whole mantra goes like this:

The maha-mantra is, in one sense, a tool in the toolbox of apps that is part of my daily existence as a spirit in the material world. But in the ultimate sense it is so much more. By chanting this mantra, we are taken through the depth of complexity of our own being, allowing us to see and transcend all the illusions that we carry in our consciousness. We come to the simple core of our being, as eternal souls in a loving relationship with God.

While my Weather Channel app can give me a grasp of my environment, and my IBooks Author app can help let loose a real dose of my productive creativity, my maha-mantra app helps me to understand who I really am, at the deepest level of my being. This is an app whose substance is entirely spiritual and which helps me to understand that the substance of my being is also entirely spiritual. It is the ultimate app to me because it contains the essence of all divinity.

By chanting the names of God—because these names are non-different from the substance of God—one’s being comes directly in touch with God. By being in contact with the vibration of God the dust of the heart, or all of the chains which keep us stuck in the vagaries of our ego, is removed. It is a very simple practice of meditation on sound vibration, yet what can be more sophisticated and wonderful than the presence of God?

It is the ultimate app because it is available to everyone, for free, at all times and is not at all contingent on one’s skin color, sexuality, political preference, or whether one is even spiritually qualified to practice it. One doesn’t have to be a Hindu to chant the maha-mantra. It enhances any kind of spiritual search because it is a universal app. It connects one to the source, the powerhouse of reality, and is inclusive of everyone.

It is the ultimate app because it’s fully open-source. It can be transmitted to anyone at any time. Whatever the technology of your being, of your personality, the maha-mantra fits into the system of your life.

It is the ultimate app because, being of eternal spiritual substance, it never breaks down, and it never needs an upgrade. It’s always in style, and it’s always available.

There have been calls for a “spiritual Steve Jobs” to appear, to innovate some of the rusted structures of spirituality. I can certainly agree with this sentiment in many ways, but it is essential to remember that real change begins within our own heart. The maha-mantra is a tool, a spiritualized lifestyle app, which allows us to come to the core of the real innovation and creativity of our true being.

In the Bhakti tradition it is said that everyone has the responsibility to become a teacher, a guide, a selfless sharer of the essence they are finding. Understanding the real tools, the real apps, of our spiritual life and seeing their immense value in our daily life can help us to become givers of the Divine, of God’s reality. It can bring us to the simplicity of our being, and allow us to give the ultimate sophistication.

IChant: The Ultimate App

→ Life Comes From Life

From Elephant Journal

Genius is a multifaceted jewel. It has many rough edges, and it doesn’t care for any mundane norms or compromises.

The package that genius is wrapped in doesn’t necessarily belie what is within but it is the duty of time to reveal that this genius— in whatever forms it takes—speaks to our body, mind and soul in many profound and challenging ways.

I think Steve Jobs was a genius. Of course the nature of Jobs’s character and his integrity as a person are quite complicated. History will see him as the “poster boy” for the troubled, difficult persona of the genius. History will also reveal that, as he expressed it to his biographer Walter Isaacson, his feeling that he follows in a line of innovators that includes Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein, was not mere hyperbole. His influence on our cultural expressions, on our connectivity and communication, and in the ways we define ourselves as biological beings in an increasingly technological world is already immense and will only grow more so.

Being a spiritual seeker, my obligation is to see the glass more than half-full when I examine the nature of such a complex and powerful personality. The Bhagavad Gita tells us that the truly wise person sees everyone on a spiritual level, beyond the body-mind construct which is the general source of all our foibles and follies. While being very clear and honest about the dark side of Steve Jobs, still I can’t help but appreciate the honest sincerity of his ambition, his own spiritual leanings and his desire to create a legacy of ideas and products that speaks to the best of human creativity at the intersection of technology and aesthetics.

What particularly strikes me about him was his attitude towards design. An early slogan of Apple was that “simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” This mirrors a saying from my own Hindu tradition, echoed by such great teachers as Mahatma Gandhi and bhakti-yoga pioneer A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, of “simple living and high thinking.” The idea is that only when we simplify, when we clear away the dust that only complicates the obvious truth, will we be able to discover the presence of enlightenment within ourselves and all around us.

In Walter Isaacson’s excellent Jobs biography, Jonny Ive—Jobs’s confidante and core designer during Apple’s incredible renaissance of the last decade— shares his take on this philosophy of simplicity:

Why do we assume simple is good?….Simplicity isn’t just a visual style. It’s not just minimalism or the absence of clutter. It involves digging through the depth of complexity. To be truly simple you have to go really deep.

We now reap the benefits of this philosophy in so many interesting ways in our lives. Our personal computers, tablets, phones and our whole conscious existence are full of these little apps that connect us and push us and inform us in ways that deftly ride along the balance of aesthetic and technology that so inspired Jobs’s overall vision.

What exactly is an app? To put it roughly, it is a little program which shapes our daily life in a particular way. We can just see it for what it apparently is, a bit of cutting-edge technology. But I want to go a little bit further, into the depth of complexity, to shine a different light of definition on this whole idea of the app.

Disclaimer: Reading the bio of Jobs and also being the recent purchaser of a wonderful, sturdy, fast and sleek Macbook Pro, I have the inklings of having become an Apple cultist. Some of the feelings are not entirely dissimilar to my spiritual practice, for both give one the sense of a particular worldview. That is why, as I was walking through New York City recently, meditating on my prayer beads, I was struck by the idea that the mantra I was chanting was also like an app and how it was the best app I had in my life.

My spiritual practice revolves around the chanting of the maha-mantra, which is part of the Bhakti (devotional) path of Hinduism. The mantra features three names of the Divine, of God, as known in the Bhakti tradition: Krishna (the masculine aspect of the Divine), Hare (the feminine aspect of the Divine), and Rama (the pleasure reservoir of the Divine). The whole mantra goes like this:

The maha-mantra is, in one sense, a tool in the toolbox of apps that is part of my daily existence as a spirit in the material world. But in the ultimate sense it is so much more. By chanting this mantra, we are taken through the depth of complexity of our own being, allowing us to see and transcend all the illusions that we carry in our consciousness. We come to the simple core of our being, as eternal souls in a loving relationship with God.

While my Weather Channel app can give me a grasp of my environment, and my IBooks Author app can help let loose a real dose of my productive creativity, my maha-mantra app helps me to understand who I really am, at the deepest level of my being. This is an app whose substance is entirely spiritual and which helps me to understand that the substance of my being is also entirely spiritual. It is the ultimate app to me because it contains the essence of all divinity.

By chanting the names of God—because these names are non-different from the substance of God—one’s being comes directly in touch with God. By being in contact with the vibration of God the dust of the heart, or all of the chains which keep us stuck in the vagaries of our ego, is removed. It is a very simple practice of meditation on sound vibration, yet what can be more sophisticated and wonderful than the presence of God?

It is the ultimate app because it is available to everyone, for free, at all times and is not at all contingent on one’s skin color, sexuality, political preference, or whether one is even spiritually qualified to practice it. One doesn’t have to be a Hindu to chant the maha-mantra. It enhances any kind of spiritual search because it is a universal app. It connects one to the source, the powerhouse of reality, and is inclusive of everyone.

It is the ultimate app because it’s fully open-source. It can be transmitted to anyone at any time. Whatever the technology of your being, of your personality, the maha-mantra fits into the system of your life.

It is the ultimate app because, being of eternal spiritual substance, it never breaks down, and it never needs an upgrade. It’s always in style, and it’s always available.

There have been calls for a “spiritual Steve Jobs” to appear, to innovate some of the rusted structures of spirituality. I can certainly agree with this sentiment in many ways, but it is essential to remember that real change begins within our own heart. The maha-mantra is a tool, a spiritualized lifestyle app, which allows us to come to the core of the real innovation and creativity of our true being.

In the Bhakti tradition it is said that everyone has the responsibility to become a teacher, a guide, a selfless sharer of the essence they are finding. Understanding the real tools, the real apps, of our spiritual life and seeing their immense value in our daily life can help us to become givers of the Divine, of God’s reality. It can bring us to the simplicity of our being, and allow us to give the ultimate sophistication.

Occupy Wall Street: Don’t Dehumanize The ‘Evil Banker’

→ Life Comes From Life

From the “Occupy Wall Street” section at The Huffington Post As a spiritual person, I have felt aloof from the Occupy Wall Street movement. I have thought about this aloofness a great deal, spoken and dialogued about it, and written about it, but I …

Occupy Wall Street: Don’t Dehumanize The ‘Evil Banker’

→ Life Comes From Life

From the “Occupy Wall Street” section at The Huffington Post As a spiritual person, I have felt aloof from the Occupy Wall Street movement. I have thought about this aloofness a great deal, spoken and dialogued about it, and written about it, but I …

Why Being a Hindu Has Made Me a Better Catholic

→ Life Comes From Life

My debut piece at the Huffington Post

I recently took a pilgrimage to Corpus Christi Church on 121st Street off of Broadway, here in New York City. This is where Thomas Merton, the great Catholic monk/mystic/author, was baptized, formally beginning a spiritual journey which has captivated and inspired millions of truth-seekers over the past few generations, myself included.

It was a special enough moment to be there, but a certain deeper resonance came as I stepped back out into the street, as I suddenly saw my past, present and future all before me. My past, raised in the Catholic tradition by my family in Detroit, as represented by Corpus Christi Church and Merton, faced me in my present situation, as an aspiring Hindu minister in New York City. I turned to my left to see the potentiality of my future, as represented by Union Theological Seminary, where I am currently applying, and where I hope to find an experience to harmonize my spiritual aspirations with my concern to be a servant to create justice in the world.

I was reminded that we owe a tremendous debt to that which has shaped us, to those who have helped to form us. We can forget this so easily, when the cult of our own individuality oversteps its boundaries. I was once again reminded that what I appreciate most of all in my own spiritual journey is gaining a greater and more loving acceptance of where I have come from, from the sacred roots of my family.

The Catholic faith of my youth planted within me the seeds to seek the truth. Now the tables have turned, as my experience of the incredible vistas of Hindu theology and practice has turned a shining light back to where I was before. In fact, I see that where I was before is very much the same as I am now. My Hindu faith has made me a better Christian.

Even as a child, the stories and wisdom I received in church and in catechism spoke to me of a profound yet simple reality: God is a person who knows and loves me dearly and deeply, and that I am also a person who can return that love in a very personal and unique way.

As I began to study the great Bhagavad-Gita, I found out that my seemingly childish impression of a personal and loving God was not actually so. It was steeped in the deepest truth. The theology of the Gita is immense and all-inclusive. The reality of the Divine is explained in three ways: God is His all-pervasive, transpersonal essence, the guide or conscience within our heart, and also a distinct individual. It is His unique personal feature which the Gita describes as being the preeminent of these three aspects.

The Gita climaxes with this passage, in which Krishna, the original Personality of God as described in Hinduism, tells his friend Arjuna that:

Always think of Me, become My devotee, worship Me and offer your homage unto Me. Thus you will come to Me without fail. I promise you this because you are My very dear friend.

I remember hearing, as a child, that God was always with me, seeing what I was doing, understanding my heart. There was never a moment where I felt threatened by this. Instead, I simply felt like I had a dear friend who would always be with me, and who would always help me, and whom I felt I could love in return. As I entered into the Bhakti faith I began to experience this simple reality in all its depth.

The path of Bhakti which I follow is a system of connection, or yoga, with God, based on the idea of loving, devotional service. Real devotional service is the giving of one’s body, mind, and words to the service of God. In the Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu, a classical 16th century devotional treatise, we read that:

“When first-class devotional service develops, one must be devoid of all material desires, knowledge obtained by monistic philosophy, and fruitive action. The devotee must constantly serve Kṛṣṇa favorably, as Kṛṣṇa desires.”

The Hindu diaspora is filled with examples of such fidelity, including A.C Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who braved the rigors of old age to bring the Bhakti tradition to the West at the age of 70 in 1965. In my exploration of my Christian roots, I come across the same mood in St. Francis of Assisi, who understood very deeply that to truly serve means to be an instrument of God. St. Francis wrote that:

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved, as to love. For it is in giving that we receive

It is in St. Francis’s particular example that I understand that Bhakti is not exclusive to any one path or faith. Bhakti means devotion, love, surrender to the will of God. My own understanding of it as a practicing Hindu helps me to see its reality as the foundation of my Christian heritage as well.

As I pray and meditate and call God’s names, it takes me into the memory of the examples before me, of my great-aunt chanting the rosary with daily and deep devotion in the living room of my childhood home, and of my grandfather taking to the Detroit airwaves in his youth to say the rosary as well.

These connections, sacred and sustaining to me, is where I really feel I have become a better Christian through my Hindu practice. It has allowed me to honor a desire in my family to carry forward a torch of devotion to God that transcends any cultural boundaries or differences.

Without the grace and knowledge I have received in my practice and life as a Hindu minister, I would not be able to approach my heritage as a Christian in such a meaningful way. This reality leaves me with a grateful heart, and a desire to go deeper into this harmony, to honor where I have come from, where I am now, and where I am meant to go.

Why Being a Hindu Has Made Me a Better Catholic

→ Life Comes From Life

My debut piece at the Huffington Post

I recently took a pilgrimage to Corpus Christi Church on 121st Street off of Broadway, here in New York City. This is where Thomas Merton, the great Catholic monk/mystic/author, was baptized, formally beginning a spiritual journey which has captivated and inspired millions of truth-seekers over the past few generations, myself included.

It was a special enough moment to be there, but a certain deeper resonance came as I stepped back out into the street, as I suddenly saw my past, present and future all before me. My past, raised in the Catholic tradition by my family in Detroit, as represented by Corpus Christi Church and Merton, faced me in my present situation, as an aspiring Hindu minister in New York City. I turned to my left to see the potentiality of my future, as represented by Union Theological Seminary, where I am currently applying, and where I hope to find an experience to harmonize my spiritual aspirations with my concern to be a servant to create justice in the world.

I was reminded that we owe a tremendous debt to that which has shaped us, to those who have helped to form us. We can forget this so easily, when the cult of our own individuality oversteps its boundaries. I was once again reminded that what I appreciate most of all in my own spiritual journey is gaining a greater and more loving acceptance of where I have come from, from the sacred roots of my family.

The Catholic faith of my youth planted within me the seeds to seek the truth. Now the tables have turned, as my experience of the incredible vistas of Hindu theology and practice has turned a shining light back to where I was before. In fact, I see that where I was before is very much the same as I am now. My Hindu faith has made me a better Christian.

Even as a child, the stories and wisdom I received in church and in catechism spoke to me of a profound yet simple reality: God is a person who knows and loves me dearly and deeply, and that I am also a person who can return that love in a very personal and unique way.

As I began to study the great Bhagavad-Gita, I found out that my seemingly childish impression of a personal and loving God was not actually so. It was steeped in the deepest truth. The theology of the Gita is immense and all-inclusive. The reality of the Divine is explained in three ways: God is His all-pervasive, transpersonal essence, the guide or conscience within our heart, and also a distinct individual. It is His unique personal feature which the Gita describes as being the preeminent of these three aspects.

The Gita climaxes with this passage, in which Krishna, the original Personality of God as described in Hinduism, tells his friend Arjuna that:

Always think of Me, become My devotee, worship Me and offer your homage unto Me. Thus you will come to Me without fail. I promise you this because you are My very dear friend.

I remember hearing, as a child, that God was always with me, seeing what I was doing, understanding my heart. There was never a moment where I felt threatened by this. Instead, I simply felt like I had a dear friend who would always be with me, and who would always help me, and whom I felt I could love in return. As I entered into the Bhakti faith I began to experience this simple reality in all its depth.

The path of Bhakti which I follow is a system of connection, or yoga, with God, based on the idea of loving, devotional service. Real devotional service is the giving of one’s body, mind, and words to the service of God. In the Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu, a classical 16th century devotional treatise, we read that:

“When first-class devotional service develops, one must be devoid of all material desires, knowledge obtained by monistic philosophy, and fruitive action. The devotee must constantly serve Kṛṣṇa favorably, as Kṛṣṇa desires.”

The Hindu diaspora is filled with examples of such fidelity, including A.C Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, who braved the rigors of old age to bring the Bhakti tradition to the West at the age of 70 in 1965. In my exploration of my Christian roots, I come across the same mood in St. Francis of Assisi, who understood very deeply that to truly serve means to be an instrument of God. St. Francis wrote that:

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

to be consoled as to console,

to be understood as to understand,

to be loved, as to love. For it is in giving that we receive

It is in St. Francis’s particular example that I understand that Bhakti is not exclusive to any one path or faith. Bhakti means devotion, love, surrender to the will of God. My own understanding of it as a practicing Hindu helps me to see its reality as the foundation of my Christian heritage as well.

As I pray and meditate and call God’s names, it takes me into the memory of the examples before me, of my great-aunt chanting the rosary with daily and deep devotion in the living room of my childhood home, and of my grandfather taking to the Detroit airwaves in his youth to say the rosary as well.

These connections, sacred and sustaining to me, is where I really feel I have become a better Christian through my Hindu practice. It has allowed me to honor a desire in my family to carry forward a torch of devotion to God that transcends any cultural boundaries or differences.

Without the grace and knowledge I have received in my practice and life as a Hindu minister, I would not be able to approach my heritage as a Christian in such a meaningful way. This reality leaves me with a grateful heart, and a desire to go deeper into this harmony, to honor where I have come from, where I am now, and where I am meant to go.

The Heart of Mantra Meditation

→ Life Comes From Life

Of all the pearls of wisdom we try to teach our students at our Gita Circle student club at New York University, this is one passage that really seems to stick out in a very visceral, practical way. The Gita is a book of everyday reasoning, a treatise of spiritual technology designed to help us take a step back from the world in order to engage with it further, as the great sages from the Himalayas to Walden Pond did for many ages before we tread upon this world.

Nowhere is this reasoning more intensely felt when we stop our everyday scheming and dreaming to ask some pertinent questions: What is my mind? How does it work? How does it exist? Why does it seem unable to focus when I need it to? Who is the “I” that is observing the mind? Our mind is more powerful, and with a much deeper memory than any visionary device from the labs at Apple or Google. It is considered the “sixth sense”, intimately linked to how the rest of our senses interact and respond, for better or for worse, to the physical reality that surrounds us.

As our students at NYU also experience, when we meditate together, we are instantly confronted with the fact that the mind prefers to be in an adversarial position. Even to just focus simply our breath for a few moments at a time in a tremendous endeavor.

Arjuna, in the Gita, agrees when he says:

Krishna, while trying to present the true reality of our bodily and mental nature as clearly as possible in the Gita, is also trying to show us that we can transcend this nature into the actuality of our being as spirit, so he responds to Arjuna’s plea by saying:

The wisdom texts of the Bhakti tradition have a specific and compassionate design to help us access this suitable practice and detachment, in the form of a specific style of meditation using mantra. Many of us are familiar with this word, but not as much as with its actual meaning. Contemporary Bhakti scholar Stephen Knapp explains:

The Heart of Mantra Meditation

→ Life Comes From Life

Of all the pearls of wisdom we try to teach our students at our Gita Circle student club at New York University, this is one passage that really seems to stick out in a very visceral, practical way. The Gita is a book of everyday reasoning, a treatise of spiritual technology designed to help us take a step back from the world in order to engage with it further, as the great sages from the Himalayas to Walden Pond did for many ages before we tread upon this world.

Nowhere is this reasoning more intensely felt when we stop our everyday scheming and dreaming to ask some pertinent questions: What is my mind? How does it work? How does it exist? Why does it seem unable to focus when I need it to? Who is the “I” that is observing the mind? Our mind is more powerful, and with a much deeper memory than any visionary device from the labs at Apple or Google. It is considered the “sixth sense”, intimately linked to how the rest of our senses interact and respond, for better or for worse, to the physical reality that surrounds us.

As our students at NYU also experience, when we meditate together, we are instantly confronted with the fact that the mind prefers to be in an adversarial position. Even to just focus simply our breath for a few moments at a time in a tremendous endeavor.

Arjuna, in the Gita, agrees when he says:

Krishna, while trying to present the true reality of our bodily and mental nature as clearly as possible in the Gita, is also trying to show us that we can transcend this nature into the actuality of our being as spirit, so he responds to Arjuna’s plea by saying:

The wisdom texts of the Bhakti tradition have a specific and compassionate design to help us access this suitable practice and detachment, in the form of a specific style of meditation using mantra. Many of us are familiar with this word, but not as much as with its actual meaning. Contemporary Bhakti scholar Stephen Knapp explains:

The Regulative Principles of Freedom

→ Life Comes From Life

The Vedic spiritual tradition, as magnificently manifested in the Bhagavat Purana, the volume of stories, fables, and lessons from the life of Krishna, the Divine Personality of God, and His followers and friends, tells us of the exceptional position of human life. In the apparatus of our human form, our body-mind-intelligence-soul framework, we have the opportunity to realize the deepest meaning and reality of our own individual self, and the meaning and reality of our relationship with God.

According to the Vedas, other life forms, the animals and plants we share this world with, do not have this same opportunity. I have noticed that to exclude the birds and bees from a life of enlightenment is a matter of fierce debate, but the science of self-realization does not run merely on the engine of instinct. The eminent Vedic sage and scholar Swami Prabhupada writes in his translation of the Bhagavat Purana that:

Animals in bodies lower than that of the human being are conscious only as far as their bodily distress and happiness are concerned; they cannot think of more than their bodily necessities of life-eating, sleeping, mating and defending. But in the human form of life, by the grace of God, the consciousness is so developed that a man can evaluate his exceptional position and thus realize the self and the Supreme Lord.1

This is where we come to an even stickier point. To run beyond our feral instincts means to understand the power of our mind and senses, and to be able to actually harness the power of our mind and senses. It is a matter of control, of discipline.

Swami Prabhupada also writes in the Bhagavat Purana:

By controlling the senses, or by the process of yoga regulation, one can understand the position of his self, the Supersoul, the world and their interrelation; everything is possible by controlling the senses.2

Spiritual life becomes very meaningful when we understand the blessings that discipline can bring into our consciousness. In the Bhagavad-gītā, Krishna explains that the mind can be either our best friend, or our worst enemy. One doesn’t have to be yearning for divinity to understand this in a very visceral and practical way. Krishna then goes on to describe certain “regulative principles of freedom”3 which allow us to be no longer held hostage by our uncontrolled minds and senses.

Followers of the bhakti tradition, from monks like myself to those who are married together, attempt to honor and hold four main regulative principles to enhance our spiritual experience. First, we are vegetarian (and vegan, if we so choose), avoiding all meat, eggs, and fish to uphold the sacred principle of ahimsa, or non-violence, which is essential to spiritual development. Second, we avoid intoxication, even caffeine and tobacco, in order to clarify and purify our vision and thought.

Third, we do not gamble or speculate, in order to avoid falling into the various illusory traps that greed may offer us. Lastly, we only practice sex in marriage, and mainly for the procreation of children, in order to defend the sacred nature of sexuality, and not allow it to be degraded into a matter of selfish lust, which can destroy any spiritual aspirations we may have.

All this talk of regulations and discipline can leave one a little hesitant, one foot in, one foot out. Discipline has fallen out of fashion in our post-post-modern world. Whereas in previous generations it was seen as a rite of passage, or even as a fashion and calling (look at the strictness and sacrifice of the American peoples supporting the war effort in World War II as an example), now it is seen as a perversion of our natural desires, of our very striving for freedom.

I hope you may be able to see from my explanation of the regulative principles that we follow in the bhakti tradition how the case is actually the opposite. Without some consideration of the power of our instincts, and a practice thereof to control and harness this power, what we may call “freedom” is actually a servitude to the negative forces of lust, envy, greed, and pride that are within us and all around us.

Discipline has to be understood beyond its surface impressions in order to see how it gives us spiritual freedom. It is a means to a tremendous end, allowing us and helping us to fully understand our loving relationship with the Divine, with God. As the father of monastic life in the West, St. Benedict describes in his Rule:

Therefore we must establish a school of the Lord’s service; in founding which we hope to ordain nothing that is harsh and burdensome.

But if, for good reason, for the amendment of evil habit or the preservation of charity, there may be some strictness of discipline do not at once be dismayed and run away from the way of salvation, of which the entrance must needs be narrow.

But as we progress in our monastic life and in faith, our hearts shall be enlarged and we shall run with unspeakable sweetness of love in the way of God’s commandments.

A firm yet healthy discipline of our body and mind helps to a deeper discipline of will and intention. To discipline our intention means to remove our selfishness. This also is not as black-and-white as it may seem on the surface, for we must also consider what it means to be selfish.

In other parts of the bhakti scriptures, it is described that the key regulative principle, over and above all

others, is to always do what is favorable for the development of one’s devotion to God, and conversely always avoid that which is unfavorable. Selfishness is that which focuses the power of our will and intention solely on the pleasure and well-being of our own self, as if we are the center of the universe, rather on the pleasure and well-being of God and all of our living brothers and sisters in this world.

There is a certain risk to be walked through here, in that if we are striving to stifle our negative selfish tendencies, we may actually go too far in the opposite direction, and lose touch with the actual needs of our self, with the ambitions we hold which can still carry us running towards God if we know how to utilize them properly.

Swami Prabhupada further explains:

Real self-realization by means of controlling the senses is explained herein. One should try to see the Supreme Personality of Godhead and one’s own self also.4

Our relationship with God is a two-way street. We are interested to know God fully, and He is interested to know us fully, and to help us offer the very best that we can to Him. It is our sacred duty to participate in this relationship, and it is a very healthy and mature attitude to always be exploring how we can best offer our talents and aspirations the very best of ourselves, to God, insuring we find the deepest fulfillment we can find as seekers and students of the Divine.

As I look forward into my own life, throwing off a certain sense of naivete and inertia, looking towards academic, social, and Interfaith opportunities to imbibe and expand Prabhupada’s mission in New York City in whatever humble way I see fit, I carry a determination to know who I am, for better and for worse. We can’t avoid, as we develop our sincere spiritual ambitions, the weeds in the garden of our heart which blur and corrupt these ambitions.

Our spiritual journey is meant to guide us into and beyond our lower nature, but not through evasion and aversion, but through a courageous and honest engagement with the loving support of our fellow community of seekers.

To come out the other side, into the best of our self that we can offer to God, we must allow the discipline we voluntarily impose on our body and mind to help also discipline our intention. What is that discipline of intention? To keep everything do wrapped in the spirit of service. As we develop the unique facets of our personal offering to God, we must keep this foundation strong in order to prevent us from wandering back into the deserts of our selfishness.

Discipline is, at its essence, an art of focus, of revelation of the best that we carry, not merely the denial of the worst we hide from ourselves and others. The principles we follow, spiritually and otherwise, to regulate our consciousness and its intention, give us a freedom that is not temporary and not relative, that is not material. It gives us the enlightenment which is our most natural instinct, and also the opportunity to give a humble yet powerful example to help others rise above.

1http://vedabase.com/en/sb/3/31/19

2http://vedabase.com/en/sb/3/31/19

3http://vedabase.com/en/bg/2/64

4http://vedabase.com/en/sb/3/31/19

The Regulative Principles of Freedom

→ Life Comes From Life

The Vedic spiritual tradition, as magnificently manifested in the Bhagavat Purana, the volume of stories, fables, and lessons from the life of Krishna, the Divine Personality of God, and His followers and friends, tells us of the exceptional position of human life. In the apparatus of our human form, our body-mind-intelligence-soul framework, we have the opportunity to realize the deepest meaning and reality of our own individual self, and the meaning and reality of our relationship with God.

According to the Vedas, other life forms, the animals and plants we share this world with, do not have this same opportunity. I have noticed that to exclude the birds and bees from a life of enlightenment is a matter of fierce debate, but the science of self-realization does not run merely on the engine of instinct. The eminent Vedic sage and scholar Swami Prabhupada writes in his translation of the Bhagavat Purana that:

Animals in bodies lower than that of the human being are conscious only as far as their bodily distress and happiness are concerned; they cannot think of more than their bodily necessities of life-eating, sleeping, mating and defending. But in the human form of life, by the grace of God, the consciousness is so developed that a man can evaluate his exceptional position and thus realize the self and the Supreme Lord.1

This is where we come to an even stickier point. To run beyond our feral instincts means to understand the power of our mind and senses, and to be able to actually harness the power of our mind and senses. It is a matter of control, of discipline.

Swami Prabhupada also writes in the Bhagavat Purana:

By controlling the senses, or by the process of yoga regulation, one can understand the position of his self, the Supersoul, the world and their interrelation; everything is possible by controlling the senses.2

Spiritual life becomes very meaningful when we understand the blessings that discipline can bring into our consciousness. In the Bhagavad-gītā, Krishna explains that the mind can be either our best friend, or our worst enemy. One doesn’t have to be yearning for divinity to understand this in a very visceral and practical way. Krishna then goes on to describe certain “regulative principles of freedom”3 which allow us to be no longer held hostage by our uncontrolled minds and senses.

Followers of the bhakti tradition, from monks like myself to those who are married together, attempt to honor and hold four main regulative principles to enhance our spiritual experience. First, we are vegetarian (and vegan, if we so choose), avoiding all meat, eggs, and fish to uphold the sacred principle of ahimsa, or non-violence, which is essential to spiritual development. Second, we avoid intoxication, even caffeine and tobacco, in order to clarify and purify our vision and thought.

Third, we do not gamble or speculate, in order to avoid falling into the various illusory traps that greed may offer us. Lastly, we only practice sex in marriage, and mainly for the procreation of children, in order to defend the sacred nature of sexuality, and not allow it to be degraded into a matter of selfish lust, which can destroy any spiritual aspirations we may have.

All this talk of regulations and discipline can leave one a little hesitant, one foot in, one foot out. Discipline has fallen out of fashion in our post-post-modern world. Whereas in previous generations it was seen as a rite of passage, or even as a fashion and calling (look at the strictness and sacrifice of the American peoples supporting the war effort in World War II as an example), now it is seen as a perversion of our natural desires, of our very striving for freedom.

I hope you may be able to see from my explanation of the regulative principles that we follow in the bhakti tradition how the case is actually the opposite. Without some consideration of the power of our instincts, and a practice thereof to control and harness this power, what we may call “freedom” is actually a servitude to the negative forces of lust, envy, greed, and pride that are within us and all around us.

Discipline has to be understood beyond its surface impressions in order to see how it gives us spiritual freedom. It is a means to a tremendous end, allowing us and helping us to fully understand our loving relationship with the Divine, with God. As the father of monastic life in the West, St. Benedict describes in his Rule:

Therefore we must establish a school of the Lord’s service; in founding which we hope to ordain nothing that is harsh and burdensome.

But if, for good reason, for the amendment of evil habit or the preservation of charity, there may be some strictness of discipline do not at once be dismayed and run away from the way of salvation, of which the entrance must needs be narrow.

But as we progress in our monastic life and in faith, our hearts shall be enlarged and we shall run with unspeakable sweetness of love in the way of God’s commandments.

A firm yet healthy discipline of our body and mind helps to a deeper discipline of will and intention. To discipline our intention means to remove our selfishness. This also is not as black-and-white as it may seem on the surface, for we must also consider what it means to be selfish.

In other parts of the bhakti scriptures, it is described that the key regulative principle, over and above all

others, is to always do what is favorable for the development of one’s devotion to God, and conversely always avoid that which is unfavorable. Selfishness is that which focuses the power of our will and intention solely on the pleasure and well-being of our own self, as if we are the center of the universe, rather on the pleasure and well-being of God and all of our living brothers and sisters in this world.

There is a certain risk to be walked through here, in that if we are striving to stifle our negative selfish tendencies, we may actually go too far in the opposite direction, and lose touch with the actual needs of our self, with the ambitions we hold which can still carry us running towards God if we know how to utilize them properly.

Swami Prabhupada further explains:

Real self-realization by means of controlling the senses is explained herein. One should try to see the Supreme Personality of Godhead and one’s own self also.4

Our relationship with God is a two-way street. We are interested to know God fully, and He is interested to know us fully, and to help us offer the very best that we can to Him. It is our sacred duty to participate in this relationship, and it is a very healthy and mature attitude to always be exploring how we can best offer our talents and aspirations the very best of ourselves, to God, insuring we find the deepest fulfillment we can find as seekers and students of the Divine.

As I look forward into my own life, throwing off a certain sense of naivete and inertia, looking towards academic, social, and Interfaith opportunities to imbibe and expand Prabhupada’s mission in New York City in whatever humble way I see fit, I carry a determination to know who I am, for better and for worse. We can’t avoid, as we develop our sincere spiritual ambitions, the weeds in the garden of our heart which blur and corrupt these ambitions.

Our spiritual journey is meant to guide us into and beyond our lower nature, but not through evasion and aversion, but through a courageous and honest engagement with the loving support of our fellow community of seekers.

To come out the other side, into the best of our self that we can offer to God, we must allow the discipline we voluntarily impose on our body and mind to help also discipline our intention. What is that discipline of intention? To keep everything do wrapped in the spirit of service. As we develop the unique facets of our personal offering to God, we must keep this foundation strong in order to prevent us from wandering back into the deserts of our selfishness.

Discipline is, at its essence, an art of focus, of revelation of the best that we carry, not merely the denial of the worst we hide from ourselves and others. The principles we follow, spiritually and otherwise, to regulate our consciousness and its intention, give us a freedom that is not temporary and not relative, that is not material. It gives us the enlightenment which is our most natural instinct, and also the opportunity to give a humble yet powerful example to help others rise above.

1http://vedabase.com/en/sb/3/31/19

2http://vedabase.com/en/sb/3/31/19

3http://vedabase.com/en/bg/2/64

4http://vedabase.com/en/sb/3/31/19

Eco-Ethics

→ Life Comes From Life

A new essay, based on a lecture from Varsana Swami, published at Elephant Journal

In 1965, teacher and scholar A.C Bhaktivedanta Swami transplanted the culture of Bhakti, or the yoga of devotion, from its roots in the ancient culture of India to the Western world.

Bhaktivedanta Swami was “ahead of his time” in the realm of living ecology. A few years before the modern ecological movement found its ground, Bhaktivedanta Swami was teaching his young students the ideal of “simple living and high thinking.” He encouraged them to break out of their industrialized and technological conditioning of mass consumption to return to a less complicated way of being, in order to free the mind for spiritual enlightenment. His students imbibed his audacity, starting farm communities in the model of the Vedic village culture in numerous places across North America, Europe, Africa, South America, Australia, and back to India.

They understood that what they were trying to do was, in a sense, both revolutionary yet eternal. The spiritual ecology and culture of the Bhakti tradition and of the Vedas is nothing new, yet to understand its precepts could bring profound auspicious change to our human condition, and to our increasingly fragile relationship with our Mother Earth.

We stand on the cusp of an abyss. We can see, with the correct lens of vision, that our collective reliance on machine and industry, on hardware and software, on an exploitative relationship with Mother Earth, has created the prospect of a total collapse of the comforts and easy access to resources that we take for granted.

Over the last forty years — beginning from the crystallized aesthetic beauty of the famous “Blue Marble” picture of our Mother Earth taken by the astronauts of Apollo 17 — we have come to understand that we all share the same planet, the same air, the same soil. We carry within us the strong, yet mostly unconscious inkling, that the Earth is our collective mother and our collective psyche.

The degree of our forgetfulness of this is the degree of pain we now all share at the breaking of our symbiosis with the planet which shelters us, nurtures us, and gives us everything she has. What would we do if the fragile relationship we have left with Mother Earth shattered?

What would we do if the chain of easy flow and access to the consumer goods and resources we take for granted broke down?

In an article by Mike Adams at Natural News, (How Fragile We Are: Why The Complexity of Modern Civilization Threatens Us All) the author bluntly states:

This is not to say that we should abandon the innovation and enthusiasm to create scientific and technical tools which can help to reverse the tide, but Gray suggests that we not exclusively worship at the same altar to the same gods who gave us what we asked for.

There is another ingredient to be added to the recipe for solution which we must consider, which is our inherent divinity.

We must go to the ground of our being, to the level of our consciousness, our thought patterns, our actions, our aspirations, our desires, to the engine of our inner psyche, towards our soul and towards God, to understand why we do what we do, and to understand why we have chosen exploitation instead of integration, dissonance instead of harmony, affluenza instead of illumination, in our sacred relationship with Mother Earth.

This platform of consciousness, where we can understand our relationship with the Divine, with God, is where we can properly begin to understand the reality of true eco-ethics. Eco-ethics is the proper protocol of thought, action, obligation, and responsibility between organisms and their collective shared environment or ecology.

Any purely materialistic angle of vision of approach to eco-ethics will reach its limitations unless we include the perspective of universal, divine wisdom. This wisdom, or dharma, is from the transcendent realm, well beyond even this material world, yet intrinsically pervading our individual and collective consciousness. Dharma is the codices and well-worn common-sense which allows us to understand our intrinsic spiritual nature, and our link to God through understanding our function and duty as beings in relation to universal law.

The key aspect of dharma in Vedic theology revolves around actualizing the full nature of our personality and our relationships. The core concept of dharma is known as sanatana-dharma, which describes the constitutional nature of our soul in the mood of loving service or devotion (Bhakti) to God, creating an all-inclusive matrix that takes in and fulfills the obligations of our relationship to family, society, humanity, and our ecology.

Those who understand the Earth as our Mother, and who really value that relationship in their heart and in their actions, approach our crisis and its potential solutions from the heart of this universal dharma, which extends across all spiritual cultures. This relationship is not to be understood in any kind of purely mythological or vapid manner. Instead, the theology of Vedic culture explains the link between our actions, and what the Earth is divinely inspired to give us.

This science of action revolves around the culture of selfless action in the mood of sacrifice. Sacrifice, in its purest form, means to give up something in order to please someone else, which is the essence and heart of all real relationships, and the heart of the Bhakti tradition, in which one tries to offer all of the fruits of one’s efforts to please God.

It is the great blessing of our Mother Earth in that she wants to give her gifts to us in order that we may offer them in return to God who has supplied her with her natural bounty.

When this cycle of receptivity, abundance, and sacrifice is fully adhered to, harmony in our ecology is fixed. The temple of our personal and collective mind, body, and soul stands strong. She is happy to provide for everyone, if everyone is utilizing her gifts properly. This traditional model of agriculture meant that, on the natural level, everything that came from the Earth went back into the Earth. This is the true synchronicity of God’s arrangement.

Any organic farmer can experience this, using manure as organic fertilizer for example. What is the contrast? What goes back into the Earth through factory farm agriculture? Blood meal, bone meal, and chemical fertilizers, all boons of the so-called “Green Revolution.” We also have synthetic nitrogen, which comes from petroleum, saturating much of our valuable soil, killing the needed microrganisms in the earth, which then creates the need for more and more chemicals to get more and more yield from the dying soil.

The classic Vedic text Mahabharata tells us that agriculture is the most noble of occupations. That we have lost sense of this, speaking from the perspective of my own experience and my own generation, is a painful knot in the heart.

I do not want to generalize here, but a personal anecdote may suffice. I spent the better part of two years at a Bhakti community in the hills of West Virginia, living as a monk, and one of my services was to assist with our organic gardening projects. I began with great enthusiasm, until the degree of effort and hard work required hit me like a ton of bricks. I relayed my difficulty to resident sage Varsana Swami, who had spent decades at this project creating the natural infrastructure, and he said that my experience was not uncommon.

He had seen many people come to work and serve there with a sense of romanticism towards the tilling of the land, and he came to see that this romanticism was not a sustainable fuel for the sacrifice that was really needed to gain access to the integrity and determination needed to give life to the land. I took this to heart in my own experience and it was a harsh lesson for me to learn, but it is one I strive to deeply imbibe and carry within me to purify my heart, so that I may be able to understand and participate in the true nobility of the community of real agriculture, on the material and spiritual level.

This sublime culture has two pillars at its core: the culture of brahminical knowledge and the protection of one of the most dynamic living beings we share this planet with, the cow. At its core, brahminical culture means knowing the difference between matter and spirit, between our eternal nature as souls and our temporary situation in these material bodies, and living our lives in an according way to actualize that knowledge.

The cow, also one of our dear mothers, helps to give all the essential gifts of proper sacrifice and offering to the Divine. Ayurvedic science tells us that milk, particularly in its natural, raw, unpasteurized state, is a tremendous boon for physical health. It also helps to develop the finer tissues of the brain, which are conducive to the development of deeper spiritual understanding.[1] The cow’s masculine counterpart, the bull/ox, was primarily responsible for tilling the land in traditional Vedic culture.

It was this abandonment (and eventual exploitation) of the cow, bull, and ox, and the conversion to tractor power which played a large part in ruining traditional local farm economies in India, America, and across the globe. Eventually from this, multinational corporations could co-opt the chain of command as to how we ate and what we grew.

Most of the foodstuffs we mainly have access to in our local shops come from California and other far-flung places. Having the food supply in the hands of big agribusiness creates, by and large, a situation of exploitation. The sacred relationship and the nobility of agriculture becomes long lost.

Because the sacred art of agriculture always returns us to the essence of relationships, to the knowledge that we are inter-dependent on others, from our fellow earthlings, from the mercy of God, for our sustenance, we get a sense of its magnanimous heart. Agriculture encourages cooperation, whereas technology and industry tend to encourage competition. The nature of competition, and the envy it produces, is destructive to the relationship between the individual and the whole. It encourages the perversion of selfishness, that the whole should be serving the parts.

Real health is when the parts are serving the whole-serving the root of everything material and spiritual, giving one’s love to God and being imparted from Him the art and actions of love and compassion.

Understanding our predicament from a spiritual perspective begins at the level of desire. We confuse our legitimate needs with our illegitimate desires. We are conditioned to believe that material prosperity is the only route to happiness in this world. Real prosperity, guided by the light of transcendent eco-ethics, means access to wisdom, health, and real progress towards the goal of life, the re-establishment of our loving relationship with God through self-realization.

God has created a perfect synergy for us to have access to. He is deeply pleased when we cooperate and sacrifice together. Our efforts combine to create a conduit for His mercy, to create an abundance that truly sustains us. We want to feel that we are part of something greater than ourselves. If we can develop our relationship to this Divine arrangement, to the Earth as our mother, goddess, and supreme teacher, through gratitude, humility, and prayer, she will help us to understand and open our heart to our relationship with the Divine, to become channels of real change in this world, unfolding the solution in every step we take.

Sources:

[1]https://www.google.com/search?q=milk+finer+brain+tissues&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a

Eco-Ethics

→ Life Comes From Life

A new essay, based on a lecture from Varsana Swami, published at Elephant Journal

In 1965, teacher and scholar A.C Bhaktivedanta Swami transplanted the culture of Bhakti, or the yoga of devotion, from its roots in the ancient culture of India to the Western world.

Bhaktivedanta Swami was “ahead of his time” in the realm of living ecology. A few years before the modern ecological movement found its ground, Bhaktivedanta Swami was teaching his young students the ideal of “simple living and high thinking.” He encouraged them to break out of their industrialized and technological conditioning of mass consumption to return to a less complicated way of being, in order to free the mind for spiritual enlightenment. His students imbibed his audacity, starting farm communities in the model of the Vedic village culture in numerous places across North America, Europe, Africa, South America, Australia, and back to India.

They understood that what they were trying to do was, in a sense, both revolutionary yet eternal. The spiritual ecology and culture of the Bhakti tradition and of the Vedas is nothing new, yet to understand its precepts could bring profound auspicious change to our human condition, and to our increasingly fragile relationship with our Mother Earth.

We stand on the cusp of an abyss. We can see, with the correct lens of vision, that our collective reliance on machine and industry, on hardware and software, on an exploitative relationship with Mother Earth, has created the prospect of a total collapse of the comforts and easy access to resources that we take for granted.

Over the last forty years — beginning from the crystallized aesthetic beauty of the famous “Blue Marble” picture of our Mother Earth taken by the astronauts of Apollo 17 — we have come to understand that we all share the same planet, the same air, the same soil. We carry within us the strong, yet mostly unconscious inkling, that the Earth is our collective mother and our collective psyche.

The degree of our forgetfulness of this is the degree of pain we now all share at the breaking of our symbiosis with the planet which shelters us, nurtures us, and gives us everything she has. What would we do if the fragile relationship we have left with Mother Earth shattered?

What would we do if the chain of easy flow and access to the consumer goods and resources we take for granted broke down?

In an article by Mike Adams at Natural News, (How Fragile We Are: Why The Complexity of Modern Civilization Threatens Us All) the author bluntly states:

This is not to say that we should abandon the innovation and enthusiasm to create scientific and technical tools which can help to reverse the tide, but Gray suggests that we not exclusively worship at the same altar to the same gods who gave us what we asked for.

There is another ingredient to be added to the recipe for solution which we must consider, which is our inherent divinity.

We must go to the ground of our being, to the level of our consciousness, our thought patterns, our actions, our aspirations, our desires, to the engine of our inner psyche, towards our soul and towards God, to understand why we do what we do, and to understand why we have chosen exploitation instead of integration, dissonance instead of harmony, affluenza instead of illumination, in our sacred relationship with Mother Earth.