SB 4.9.16 – The mind’s contradictory currents of emotions are purified and harmonized by devotional meditation

16 Sep 2013 – Appearance Day of Sri Jiva Goswami

→ ISKCON Desire Tree

16 Sep 2013 – Parsva Ekadashi

→ ISKCON Desire Tree

16 Sep 2013 – Sri Vamana Dwadashi : Appearance of Sri Vamana Deva

→ ISKCON Desire Tree

Maha-Mantra Week!

→ The Toronto Hare Krishna Blog!

.jpg) ** PLEASE SEE UPDATE ON DOUBLE DECKER BUS BELOW! **

** PLEASE SEE UPDATE ON DOUBLE DECKER BUS BELOW! **On September 18, 1965, His Divine Grace A.C.Bhaktivedanta Swami Srila Prabhupada stepped off the ship Jaladutta onto American soil in Boston. The rest is history!

** UPDATE: Due to rain today, we are postponing the Double Decker Harinam event to a later date. HOWEVER, there is still a wonderful program in the evening. So please come out for a sweet evening as the local disciples of our dear most Srila Prabhupada all come together to share their personal experiences with him! **

September 13th, 2013 – Radhastami Darshan

→ Mayapur.com

The post September 13th, 2013 – Radhastami Darshan appeared first on Mayapur.com.

Impetus to Love

→ travelingmonk.com

Radhastami Festival of Flowers 2013 at Kalachandji’s Hare Krishna Temple in Dallas (133 photos)

→ Dandavats.com

Five hundred years ago in India, Kalachandji, literally translated as "the beautiful moon-faced one," was worshipped as the Supreme Personality of Godhead by thousands of devotees. Impeccable craftsmen constructed an elaborate temple for Him; famous artisans decorated it. Accompanied by drums, cymbals and tambouras, His followers filled the halls with melodious prayers throughout the day, and the air was sweet with myriad varieties of richly fragrant incense. Read more ›

Five hundred years ago in India, Kalachandji, literally translated as "the beautiful moon-faced one," was worshipped as the Supreme Personality of Godhead by thousands of devotees. Impeccable craftsmen constructed an elaborate temple for Him; famous artisans decorated it. Accompanied by drums, cymbals and tambouras, His followers filled the halls with melodious prayers throughout the day, and the air was sweet with myriad varieties of richly fragrant incense. Read more › HH Bhakti Purusottama on Radhastami

→ Mayapur.com

His Holiness Bhakti Purushottam Swami Maharaj, An Author of book name “Srimati Radharani”, speaks on the significance of the appearance of Radharani, on this auspicious Radhastami day. www.bpswami.com

The post HH Bhakti Purusottama on Radhastami appeared first on Mayapur.com.

Radhastami 2013-Greetings and Initiation ISKCON Durban (30 photos)

→ Dandavats.com

The Sri Sri Radha Radhanath Temple (Hare Krishna Temple) places the bustling suburb of Chatsworth on the map as a tourist destination. Situated approximately 20km south of the Durban City Centre, its three domes of white and gold rises above a dazzling octagonal roof. The temple has been acclaimed as an architectural masterpiece – a spiritual wonderland. Although, designed and constructed in the 1980′s, its design is a combination of the traditional, contemporary and futuristic; and simultaneously a fusion of concepts showcasing “east meets west”. The ancient “vastu purusha mandala” formula is imbibed in its geometrical lay-out with shapes such as circles, triangles, squares and octagons, holding great spiritual symbolism and philosophical meaning enhanced by its unique setting in the midst of a moat of water and water features, surrounded by a sprawling luscious lotus shaped garden. Read more ›

The Sri Sri Radha Radhanath Temple (Hare Krishna Temple) places the bustling suburb of Chatsworth on the map as a tourist destination. Situated approximately 20km south of the Durban City Centre, its three domes of white and gold rises above a dazzling octagonal roof. The temple has been acclaimed as an architectural masterpiece – a spiritual wonderland. Although, designed and constructed in the 1980′s, its design is a combination of the traditional, contemporary and futuristic; and simultaneously a fusion of concepts showcasing “east meets west”. The ancient “vastu purusha mandala” formula is imbibed in its geometrical lay-out with shapes such as circles, triangles, squares and octagons, holding great spiritual symbolism and philosophical meaning enhanced by its unique setting in the midst of a moat of water and water features, surrounded by a sprawling luscious lotus shaped garden. Read more › Radhastami flower dress @ ISKCON Vrindavan (108 photos)

→ Dandavats.com

“Srimati Radharani is the mother of the universe, the spiritual mother of all souls. And the concept of mother is the most sacred symbol—that of purity, selflessness, caring, sharing, nurturing, and love. That is why our sacred mantra is the holy names. It is the holy names in the vocative. Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare / Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare Read more ›

“Srimati Radharani is the mother of the universe, the spiritual mother of all souls. And the concept of mother is the most sacred symbol—that of purity, selflessness, caring, sharing, nurturing, and love. That is why our sacred mantra is the holy names. It is the holy names in the vocative. Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare / Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare Read more › Sri Radhastami Morning Program and Abhishekam in Mayapur (75 photos)

→ Dandavats.com

An abhisheka is a religious bathing ceremony. The word abhisheka means a sprinkling. It is derived from the root sic, to wet, and with the prefix abhi, "around," abhisheka is literally, "wetting around." An abhisheka is the bathing part of a puja that usually is done with sacred water. In puja, a Deity is called, seated, greeted, bathed, dressed, fed and praised. The bathing of the Deity is the abhisheka part of the puja. In some cases, the main focus of the puja is the bathing ceremony itself. Read more ›

An abhisheka is a religious bathing ceremony. The word abhisheka means a sprinkling. It is derived from the root sic, to wet, and with the prefix abhi, "around," abhisheka is literally, "wetting around." An abhisheka is the bathing part of a puja that usually is done with sacred water. In puja, a Deity is called, seated, greeted, bathed, dressed, fed and praised. The bathing of the Deity is the abhisheka part of the puja. In some cases, the main focus of the puja is the bathing ceremony itself. Read more › Two Ecstatic ‘GBCs’ On London Harinam (7 min video)

→ Dandavats.com

(For the purpose of this brief report, GBC stands for - Great British Chanters) Read more ›

(For the purpose of this brief report, GBC stands for - Great British Chanters) Read more › Radhastami Celebrations at ISKCON Vrindavan, September 13, 2013 (64 photos)

→ Dandavats.com

The Krishna Balaram Mandir was personally established by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada on Rama Navami in 1975. The temple is situated in Raman Reti, Vrindavan, U.P., where the Supreme Lord Sri Krishna displayed His transcendental pastimes 5,000 years ago. Read more ›

The Krishna Balaram Mandir was personally established by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada on Rama Navami in 1975. The temple is situated in Raman Reti, Vrindavan, U.P., where the Supreme Lord Sri Krishna displayed His transcendental pastimes 5,000 years ago. Read more › Amala and Nadia’s Radhastami morning kirtana – most wonderful

→ SivaramaSwami.com

Sivarama Swami 13th Morning

→ SivaramaSwami.com

Madhva Prabhu 13th Morning

→ SivaramaSwami.com

Candramauli Swami speaks on Radhastami (Hungarian/English)

→ SivaramaSwami.com

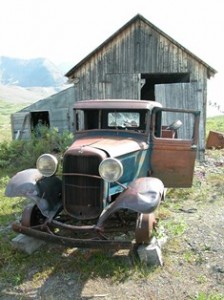

Giri’s Mechanic Shop

→ New Vrindaban Brijabasi Spirit

(next to Nityo’s house on the road to the old Vrindaban farmhouse)

Giri provides the following auto services:

Brakes, shocks, struts, bearings, bushings, some exhaust welding, starters, alternators, ball joints, tie rod ends, radiators, cv boots and joints AND just about any other mechanical problem that may occur.

Thanks,

Giri

304 843 1765

Radhastami kirtans beginning Thursday night with Madhava Prabhu

→ SivaramaSwami.com

Be ready for more over the next 2 days.

If one likes to study scripture more than do other services does that make one a jnani and not a bhakta?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

As the consciousness at conception determines the kind of soul coming to the womb isn’t abortion desirable during pregnancy after rape so as to avoid unwanted progeny?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

How can an IAS officer help in sharing Krishna consciosness since India is a secular country?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

From: Rishi

Please tell how can an IAS officer serve Srila Prabhupada and his mission.

How can he help in preaching and book distribution ?? As India is a secular country and IAS officer in his public life is expected to be secular and not promoting any particular religion. Despite all that, if an IAS officer is a vaishnava, how can he help in preaching activities and book distribution especially, with all the resources and power he possess ?

Can a scientist who accepts evolution practice Krishna consciousness?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

I have a doctorate in biology and have studied evolution for many years. I find the evidence for it quite strong and the arguments that devotees give against it childish. But whenever I bring up the issue with devotees, conflicts erupt and they brand me as faithless. How can I practice Krishna consciousness without such conflicts?

When Krishna appeared at midnight according to the time in Mathura why do we fast on Janmashtami till midnight according to the local time at different places?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

Achyuta Gopi mataji – Day 4 of Polish Woodstock 2013

→ Gouranga TV - The Hare Krishna video collection

Achyuta Gopi mataji – Day 4 of Polish Woodstock 2013

ISKCON Scarborough- 1st Jagannath Cultural festival 2013 – Slideshow and parade

→ ISKCON Scarborough

Radha’s Krishna

→ ISKCON Malaysia

Please Join The Japa Group

→ Japa Group

Renewable Energy Provides 14% of US Electrical Generation During First Half of 2013

→ View From a New Vrindaban Ridge

WASHINGTON, D.C. — According to the latest issue of the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) “Electric Power Monthly,” with preliminary data through to June 30, 2013, renewable energy sources (i.e., biomass, geothermal, hydropower, solar, wind) provided 14.20 percent of the nation’s net electric power generation during the first half of the year. For the same period in 2012, renewables accounted for 13.57 percent of net electrical generation.

Moreover, non-hydro renewables have more than tripled their output during the past decade. They now account for almost the same share of electrical generation (6.71 percent) as does conventional hydropower (7.49 percent). Ten years ago (i.e., calendar year 2003), non-hydro renewables provided only 2.05 percent of net U.S. electrical generation.

Comparing the first six months of 2013 to the same period in 2012, solar thermal & PV combined have grown 94.4 percent (these additions understate actual solar capacity gains. Unlike other energy sources, significant levels of solar capacity exist in smaller, non-utility-scale applications – e.g., rooftop solar photovoltaics). Wind increased 20.1 percent and geothermal grew by 1.0 percent, while biomass declined by 0.5 percent while hydropower dropped by 2.6 percent. Among the non-hydro renewabes, wind is in the lead, accounting for 4.67 percent of net electrical generation, followed by biomass (1.42 percent), geothermal (0.43 percent), and solar (0.19 percent).

The balance of the nation’s electrical generation mix for the first half of 2013 consisted of coal (39.00 percent - up by 10.3 percent), natural gas and other gas (26.46 percent - down by 13.6 percent), nuclear power (19.48 percent - up by 0.2 percent), and petroleum liquids + coke (0.66 percent - up by 15.6 percent). The balance (0.21 percent) was from other sources and pumped hydro storage.

Every year for the past decade, non-hydro renewables have increased both their net electrical output as well as their percentage share of the nation’s electricity mix. Moreover, the annual rate of growth for solar and wind continues in the double digits, setting new records each year.

Filed under: Cows and Environment

Journal Roulette

→ Seed of Devotion

I'm going to conduct a little experiment.

I'm going to open up several random journals and open to a random page. I'll then copy down a paragraph or two from those pages. Let's call it Journal Roulette, shall we?

You ready?

August 1st, 2011 (age 24)

Baja, Mexico [summer Bus Tour]

I write this late at night in the front seats of the bus. We're parked on the cliff, and the ocean waves crash far below in whispers. Everyone's sleeping.

December 24th, 2005 (age 18)

Oaxaca, Mexico [winter Bus Tour]

I pull plants out of the bag... and pull out the ugliest coconut head I have EVER laid eyes on. It's carved and painted to the likeness of a pirate with an eye-patch and an ugly grin.

I fight the urge to drop it and scream through the numbness. Hoots and raucous laughter erupt around the bus...

Why couldn't I have gotten a pair of earrings???

December ?, 2008 (age 21)

Tirupati, India

I stormed off to Brindavan, the mystical garden of Anantalvar, the place where his soul resides. There, I found my solace at the lake. A sadhu was chanting his gayatri on the ghat steps, and his presence soothed me. Otherwise the entire garden and ghat was empty in the cool evening.

November 1st, 2011 (age 24)

Gainesville, Florida

I'm sitting here in the eveningtime writing this on the Plaza of the Americas, and a young man just walked by me with a wave and a smile. [Puzzled], I called out to him, "Do I know you?"

He turned around and smiled. "No. You just look happy and peaceful. That's all."

I beamed. "Why, thank you!"

He waved again, turned around, and kept walking.

May 1st, 2013 (age 26)

Mayapur, India

Last night I spent time with Jahnavi at her place. We shared such deep secrets and realizations with each other. Shame, guilt... I feel so deeply grateful to have shared with someone this secret of shame that has been in my heart for many months now. We actually discussed it - not that I just said it and it was over. Wow. I feel like I was cleaning out and letting go of a burden. Last night I slept very peacefully; I had simple and peaceful dreams.

July 26th, 2001 (age 14)

Kailua-Kona, Hawaii

I have been through major ups and major downs, but you - a journal that reflects my own thoughts - are a patient friend who is always there to help me see the light. It is almost as if Krishna himself was guiding me. I could not have found anyone more dependable than a piece of paper, a pen, and my own soul.

Radhastami Morning, September 12, New Dvaraka, Los Angeles

Giriraj Swami

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

“Srimati Radharani may be in the most intense throws of ecstasy in separation from Krishna, but still She thinks of the welfare of others. For us fallen souls in the material world Her compassion is vey important because we are in need of mercy, and to the extent that we cry out to Her through chanting the maha-mantra—’Hare’ is a form of address for Radharani—Her heart will melt. It is already melted, but it will melt even more and She will shower Her mercy upon us. In The Nectar of Devotion Srila Prabhupada writes that because Krishna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead, it is difficult to approach Him, but He has a compassionate side, and that compassionate side is represented by Srimati Radharani. Therefore we can approach Krishna through His compassionate side—Srimati Radharani. And we do that when we chant the Hare Krishna maha-mantra. As Srila Prabhupada said, the chanting should be like “the genuine cry of a child for its mother”: ‘O Mother Hara, please help me attain the grace of the Supreme Father, Krishna’—and “the Lord reveals Himself to the devotee who chants this mantra sincerely.”

SB 4.9.15 – Bhakti-anukula jnana highlights the difference between us and the Lord and thereby increases our attraction to him

→ The Spiritual Scientist

The Lord reciprocates as is our mentality and sincerity

→ The Spiritual Scientist

The devotees are constantly engaged in the Supreme Lord’s service. The Lord understands the mentality and sincerity of a particular living entity who is engaged in Krsna consciousness and gives him the intelligence to understand the science of Krsna in the association of devotees. Discussion of Krsna is very potent, and if a fortunate person has such association and tries to assimilate the knowledge, then he will surely make advancement toward spiritual realization.

07.03 – Focus on how close you are, not how far you are

→ The Spiritual Scientist

Our struggles as a devotee-seeker may dishearten us: “I have no love for Krishna. Even when I pray, chant or take darshan, my mind goes off in nasty directions. I am so far away from Krishna.”

Yes, we have a long way to go in our journey to Krishna. But that’s only a part of the story.

The other part is that we are so close to Krishna. The Bhagavad-gita (07.03) underscores that those who have made even a little headway on the journey to him are rare and special – they are one among thousands. By Krishna’s inconceivable and causeless mercy, we are among those few souls.

If we look at the vastness of material existence and the sheer number of mazes in which souls can stay lost in forgetfulness of Krishna, we can realize how fortunate we are to have found the way to Krishna and to be moving forward along that way. Considering that we too have probably wandered among those mazes in various nonhuman and human bodies, we are actually so close to Krishna.

Far closer than most living beings in material existence.

And far closer than what we have ever been since the start of our material existence.

Despite our conditionings, despite our half-heartedness, against all odds, Krishna has got us so close. He will take us all the way across the finishing line back to him – if we just let him.

If we obsess on how far we are, we will give up and ruin our chance of returning home. A chance that we have got after so many lifetimes.

If instead we focus on how close we are to the finishing line, we will stay encouraged and enthused to keep pressing on – even when the finishing line seems far away.

***

07.03 - Out of many thousands among men, one may endeavor for perfection, and of those who have achieved perfection, hardly one knows Me in truth.

Happy Radhastami to all Dandavats Readers! Who is Srimati Radharani?

→ Dandavats.com

As the material world is manipulated under the external energy, the spiritual world is conducted by the internal potency. That internal potency, called the Hladini Sakti, is Srimati Radharani Read more ›

As the material world is manipulated under the external energy, the spiritual world is conducted by the internal potency. That internal potency, called the Hladini Sakti, is Srimati Radharani Read more › Bliss In Israel

→ travelingmonk.com

Festival of Colors Service Opportunity in New Vrindaban – 09-14-13

→ New Vrindaban Brijabasi Spirit

Haribol