Prabhupada Letters :: Anthology 2013-07-29 01:26:00 →

Prabhupada Letters :: 1975

Websites from the ISKCON Universe

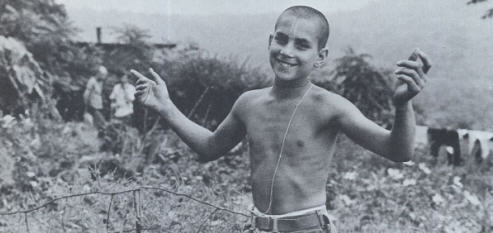

(Kadamba Kanana Swami, 23 July 2013, Durban, South Africa, First grain ceremony)

Growing up in a family of devotees, it is mentioned in the scriptures, is someone who is finishing something from a previous life; one resumes devotional service! The early impressions in life are the most powerful. Whatever the impressions are of a child for the first three years, they influence their whole life. This is actually the most important time. The child gets a lot of love, support and Krsna consciousness because that is Krsna consciousness. It is based on loving Krsna and Krsna loves all living beings. Krsna consciousness will only conquer the heart of a child if it is given with love; one cannot give it with discipline. We, ourselves, must be very Krsna conscious otherwise how can we really give Krsna with love. Arguments don’t convince so deeply. Love for Krsna is what convinces us the most so our children make us Krsna conscious!

Growing up in a family of devotees, it is mentioned in the scriptures, is someone who is finishing something from a previous life; one resumes devotional service! The early impressions in life are the most powerful. Whatever the impressions are of a child for the first three years, they influence their whole life. This is actually the most important time. The child gets a lot of love, support and Krsna consciousness because that is Krsna consciousness. It is based on loving Krsna and Krsna loves all living beings. Krsna consciousness will only conquer the heart of a child if it is given with love; one cannot give it with discipline. We, ourselves, must be very Krsna conscious otherwise how can we really give Krsna with love. Arguments don’t convince so deeply. Love for Krsna is what convinces us the most so our children make us Krsna conscious!

In this way, everyone blesses everyone else and this is a wonderful aspect to all of this. The ritual in a sense is secondary. The essential thing of a gathering like this is the blessings of all the devotees. We come together; we take the opportunity of the first grains (ceremony) to get some blessings.

Culture is very nice because all these things are part of the rites of passage which give meaning at different junctions in life; just as when one first goes to school or gets married and so on… all these things are to be observed with a nice ceremony so that it makes a deep impression. She (the child) may not remember but we all do. When she reached to the Bhagavatam, then everyone smiled…

It says that to bring up a child, it doesn’t just take the parents, it takes a village. So this is our village here – the community of devotees.

If people are advised not to collect too many goods, eat too much or work unnecessarily to possess artificial amenities, they think they are being advised to return to a primitive way of life. Generally people do not like to accept plain living and high thinking. That is their unfortunate position.

Human life is meant for God realization, and the human being is given higher intelligence for this purpose. Those who believe that this higher intelligence is meant to attain a higher state should follow the instructions of the Vedic literatures. By taking such instructions from higher authorities, one can actually become situated in perfect knowledge and give real meaning to life.

Dallas Morning News,

Dallas Morning News,Each week we will post a question to a panel of about two dozen clergy, laity and theologians, all of whom are based in Texas or are from Texas. They will chime in with their responses to the question of the week. And you, readers, will be able to respond to their answers through the comment box.

Leaders of the Evangelical Immigration Table will meet on Capitol Hill Wednesday to continue praying for and advocating for a broad immigration reform. In other words, they want a package that goes beyond simply securing the border.

This group has a long list of supporters. They represent evangelicals from both conservative and liberal traditions. And they have a set of principles that guide their work. You can read all of this at this link:

This group also gathers regularly and continues to press for reform. Their outreach includes meeting with legislators, reaching out to media and generally lifting up Capitol Hill in prayer. They also are attracting press because evangelicals were not as outspoken for change back in 2007, when the last immigration debate took place. Here is an article from The Atlantic that details their work.

But this debate is about to get into some brutal politicking. The GOP-led House is clearly not interested in going as far as the Democratic-led Senate in crafting a comprehensive plan. For example, most House Republicans do not appear very eager to grant illegal immigrants a chance to earn citizenship or some kind of legal status.

Yet evangelicals could be the trump card. The Atlantic piece described the role of evangelicals this way, quoting Ali Noorani of the pro-reform National Immigration Forum: “Pro-reform groups view these efforts as essential. ‘I don’t think a House vote happens without evangelicals,’ Noorani said. ‘The only reason it happens is because evangelicals are engaged.’”

So, my question is this: How hard should evangelicals — or any other religious groups in favor of immigration reform — push for change?

This debate is not likely to move ahead in the House without a great deal of arm-twisting. But is that the role for people of faith?

NITYANANDA CHANDRA DAS, minister of ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness), Dallas

Every spiritual minded person must stand strong against activities that are in opposition to spiritual principles. However those who have deeper spiritual realizations may have a different battle than those of lesser realizations. For example, one party may be fighting against the symptoms of ignorance and the other party may fight against the root cause of it. Both are doing great work according to their realization, however the latter group's action will have a deeper, more profound effect. For the cause may have many symptoms, which people can address separately, but if you cure the cause the symptoms disappear.

The ultimate cause of difficulties and injustice is that people misidentify themselves with their temporal material body rather than seeing that the soul/consciousness is separate, transcendent, and eternally related to God with love.

To see all responses of the TEXAS Faith panel click here.

Imagine if you can hearing a name called in the Temple (you’ve not heard this name before but it’s not a devotional one); the person calling it is trying to get the attention of the individual but as you look around all you see is familiar faces.

Who are they calling?

As they come running they approach the temple president again use a name you yourself have never heard them called (realizing this is the first time you’ve heard their non-initiated name); the person then enters into a discourse.

What puzzles you more is that the person is a temple devotee, why such break in temple etiquette?

Indeed if the temple president didn’t correct them sternly one of the senior devotees would at some stage that day; initiated names are as we know important.

However it appears that when it comes to letters we send to devotees we simply ignore this etiquette sending them post in their nu-initiated name. You may say NO BIG DEAL SO WHAT. But if we cannot be bothered to address a label properly then it shows our mentality overall when it comes to addressing them more formally face to face (Yep whatever).

Sadly the biggest culprits is the temples themselves when sending out mail shots even when the error is pointed out Yes you guessed it not our fault it’s the IT systems we use, yes the pre-windows ere computers could do something our modern ones can’t add a simple field which means the initiated name is recognized and used.

Now I know there are occasions that here in the UK my non-initiated name has to appear, for the temple to claim back the gift-aid on donations the name they submit has to appear on the electoral/tax register; so some letters without an initiated name could be forgiven,

But an etiquette principle of how we address devotees has to be upheld when writing in all other instances; especially if as is the normal case they wish for a donation towards festivals.

I give an example again a letter from ISKCON non devotional name used, nice well presented but Hay I go to this temple every month what gives? Especially as it asks if I would be willing to donate may be £70.

Now another temple also wrote to me non ISKCON (I don’t know how they got my address) their was one notable addition Yes My Initiated Name indeed a notation of the glories of my Guru Maharaja; who can’t be impressed with that.

It’s a small detail but one that may be should be taken more seriously.

For the letter is like the call out down the corridor to get the persons attention; the more personal the more favourable the response; after all if we fail to develop personal relationships with others then how can we expect to develop one with Krishna?

It’s a point all those responsible for mail in temples should ponder I feel.

From: Praveen

Could you please provide the disciplic succession in which the knowledge has come down to Krishna Das Kaviraj Goswami to be able to compile Chaitanya Charitamrita, especially there are some intimate past times of Lord Chaitanya Mahaprabhu like showing the universal form which was shown only to Advaita acharya and Nityanand prabhu - meaning how were they revealed to him.

Also how has that knowledge of Chaitanya Charitamrita come down in disciplic succession could you please explain in detail.

From: vivek

how can i best understand the gita and its practical application? do you have a book or lectures that i can listen to which explains the gita the best?

From Anand

if one has suffered his part of karma in heaven or hell . then why that karma of previous life act in this life also. my point is that it is better to get a fine when you actually break the signal then to get fine years after when you have totally forgotten about it. (i have asked this question based on what i heard from people about transmigration)please also give reference to a book that explains this transmigration process in detail

From Anand

See photos HERE

The GBCs for Mayapur, along with other leaders, attended a five day meeting to discuss various issues of Sridam Mayapur development.

By Hayagriva Dasa Adhikari

“You have New York, New England, and so many ‘New’ duplicates of European countries in the USA, why not import New Vrindaban in your country?” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 3/17/68)

Within the past three years communes have been popping up throughout America. They tend to sprout in the unlikeliest places, and they are conceived and nourished by the most diverse people. Practically all of them have “hippy” images and are inspired by current concern over ecology (O for a breath of gasp! air!) and a semi-Thoreauesque “let’s-get-back-to-the-earth-and-live-cheaply-and-simply” longing. Many of the members are just tired of “hassling” with urban culture too many peace marches, too many drug busts and many are just tired of their own image as underground culture freaks. Most of them inspire one another and, ironically enough, manage to superimpose their urban life-style upon the country.

The hills of West Virginia, however, are a tough and tender cradle for a different type of communal project. Although New Vrindaban is not yet three years old, it is one of the oldest and largest communes of the crop which arose in the last half of the Sixties. As fate has it, “hippy” communes sprout and die quickly discouraged by the first winter, diversity of interests, drug and sex confusion, local inhabitants but New Vrindaban, unique in conception and purpose, is expanding with a view to solidly establishing a genuine Vedic culture in America.

The “seed-giving father” is His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, founder-acarya of the Hare Krsna movement in the West, who conceived of New Vrindaban before coming to America from India in 1965. In his prospectus for the movement printed in 1966, Srila Prabhupada wrote that one of the five purposes of the International Society for Krsna Consciousness is: “To erect for the members, and for society at large, a holy place of transcendental pastimes dedicated to the Personality Krsna.”

Vrndavana is the forest where Lord Sri Krsna sported as a boy and is also the name of the supreme planet in which the Personality of Godhead eternally abides. New Vrindaban is an implantation in the Western world of the ideals established five thousand years ago in Vrndavana, India, by Lord Sri Krsna. The roots are ancient, but the fruits of the tree are ever new.

The integral or Utopian community is not new in American history. Indeed, it has been a most basic part of our history from the Puritan experiment at Massachusetts Bay in the 1630′s to this New Vrindaban experiment today. Despite differences of dress and circumstance, the aim of most of these communal experiences has been basically the same: to find a setting in which God consciousness can be pursued so that man’s journey through this temporary sphere of material existence can be successfully completed to transfer his consciousness to the Absolute or to the realms of eternality. The conception of a community of souls is founded on the premise that such a transferral is easier collectively than individually.

Different experimenters have expressed the ideal community in different ways. Some have been more successful than others, largely depending on the authority on which the community is based. Some have been based upon a strong personal authority (Brigham Young or John Smith and the Mormons, or Humphrey Knolls and the Socialist Community at Oneida). New Vrindaban is different in that it is based on perfect authority. If one analyzes the various communities of the past, he can see that they have fallen apart because they could not agree as to what was the center of the community, what was its aim, what was its unifying point. The most successful communities tended to be those that were strongly religious. They could unify on the basis of the worship And obviously where the concept of God is most agreed upon, that community will be most united and most harmonious. New Vrindaban is based on God, or “Krsna,” as revealed by the Spiritual Master and the information given by God Himself in the Vedic scripture Bhagavad-gita. It is because these authorities are agreed upon that there is unity of purpose at New Vrindaban.

Communal living has currently provoked many articles by journalists and many essays by students. In a recent survey, one graduate student asked one of the New Vrindaban leaders: “What is your advice to beginning communes?” The reply was instant: “Don’t try to start one without Krsna.” It was pointed out that the commune wouldn’t have lasted its first winter without faith in the instructions of the Spiritual Master Srila Prabhupada and a lot of Hare Krsna chanting. Communal living isn’t all honey and wildflowers, though there are plenty of both. First there is the seemingly eternal problem of finances, then manpower. There must be money to buy property and building materials; then the building must be carried out by: members who know more about construction than just nailing. Thus far New Vrindaban has twelve cottages and one main farmhouse, barn and pavilion constructed. Wells must be dug, sewage disposed, roads built, land plowed, supplies brought in. Then there must be heat for the winter stoves, firewood or oil and hay and grain for the cows and horses, which are quite expensive for the winter when there’re a dozen cows. And there’s more to crops than just throwing in seeds. In brief, there is so much involved in getting a commune functioning that it is no wonder that most of them fold and die before the first spring flowers bud. The advice: don’t try to start one without Krsna.

When Krsna descended from the spiritual sky 5,000 years ago, He gave a practical example of the ideal life when He sported as a cowherd’s boy. He showed that man can live very simply and reserve his main energies for what Emerson called “plain living and high thinking” by protecting and cultivating the cow. So one of the aims of New Vrindaban is protecting the cow and demonstrating the value of the cow in providing for the sustenance of man. At New Vrindaban, the cow is more than just an ordinary animal. Aside from the fact that Krsna was very fond of cows and that the cow is considered man’s second mother in the Vedas (dhenu mata), the cow represents man’s religion or man’s yearning and love for God. When such yearning and love are slaughtered, then man is left with the empty shell of materialism, or life without principle and meaning. So one of the main functions of New Vrindaban is to demonstrate the humane practicality of cow protection.

The Perfect Society

Most of the full time members at New Vrindaban come from the big cities New York, Los Angeles, etc. Although most come direct from the Krsna temples, the only requirement for entrance is sincerity. The community serves as a training camp in Krsna consciousness and, ideally, as an example of a perfect Krsna conscious community to show the practicality and applicability of the philosophy to communal living. The temples established in various cities are able to work very effectively to a certain degree, but they are not able under the present situation to exhibit what a perfect society is like. For that reason New Vrindaban is envisioned as a society where all the residents are Krsna conscious and where all of the activities are directed toward the ultimate goal. It is not that Krsna consciousness is inactive in any sense. The practitioners engage in work which may appear to be ordinary work but is in fact devotional service due to the change in consciousness. Everyone in New Vrindaban is aware that his work is devotional in character and is directed to the Supreme Godhead because the factual proprietor of the land, of the buildings, of the temples, of the food, of the vehicles, tools and all the varied paraphernalia is Krsna. The awareness of Krsna’s proprietorship enables the devotee to advance in Krsna consciousness while executing his daily chores.

In New Vrindaban this remembrance of the Supreme’s proprietorship is facilitated because the atmosphere has been Krsnaized: by the mere touch of sound Hare Krsna the hills, pastures, forests and streams are transported out of the State of West Virginia into the spiritual sky of Vaikuntha. As the Spiritual Master, Srila Prabhupada, writes: “We can remember Krsna in every moment. We can remember Krsna while taking a glass of water because the taste of water is Krsna. We can remember Krsna as soon as we see the sunlight in the morning, because the sunlight is a reflection of Krsna’s bodily effulgence. And as soon as we see moonlight in the evening we remember Krsna because moonlight is the reflection of sunlight. Similarly, when we hear any sound we can remember Krsna because sound is Krsna, and the most perfect sound, transcendental, is Hare Krsna, which we have to chant 24 hours. So there is no scope of forgetting Krsna at any moment of our life provided we practice in that way.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 1/15/68)

The atmosphere of New Vrindaban is suitable for such remembrance process it is cosmic, rural, woodsy. Under the Milky Way, kirtana expands. Orion, the Pleiades, Sagittarius, Virgo all vibrate to the cymbal rhythm, the chants broadcast from the mountains of planet earth. The firmament revolves about the mahamantra, the chanting of Hare Krsna. There is kirtana, group chanting, every morning and evening. Offerings to the Deity are performed before dawn and five times throughout the day. The morning kirtana is usually over before sunrise. Then morning prasadam is taken, usually cereal, and the day’s chores begin. There is much to do at New Vrindaban, and all participate.

The conception and purpose of New Vrindaban are best set forth specifically in the letters of the Spiritual Master.

“Vrndavana conception is that of a transcendental village, without any botheration of the modern industrial atmosphere. My idea of developing New Vrindaban is to create an atmosphere of spiritual life where people in the bona fide orders of social divisions, namely, brahmacaris, grhasthas, vanaprasthas, sannyasis, or specifically brahmacaris and sannyasis and vanaprasthas, will live there independently, completely depending on agricultural produce and milk from the cows.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 8/17/68)

“To retire from activities is not a very good idea for the conditioned soul. I have very good experience, not only in our country, but also in your country, that this tendency of retiring from activities pushes one down to the platform of laziness, and gradually to the ideas of the hippies. One should always remain active in Krsna’s service, otherwise strong maya will catch him and engage him in her service. Our constitutional position is in rendering service; we cannot stop activity. So New Vrindaban may not be turned into a place of retirement, but some sort of activities must go on there. If there is good prospective land, we should produce some grains, flours and fruits and keep cows, so that those living there may have sufficient work and facility for advancing in Krsna consciousness. In India actually Vrindaban has now become a place of the unemployed and beggars. Kirtanananda has already seen it. And so there is always a tendency toward such degradation if there is no sufficient work for service of Krsna.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 7/14/68)

From the beginning, as Srila Prabhupada suggested, the program at New Vrindaban is geared to enable the student to progress along the path of devotional service; so there is work going on all the time. And the program is sufficiently diversified to accommodate a variety of talents, dovetailing them in Krsna’s service.

As in the many transcendentalist farms in 19th century America, the concept of life at New Vrindaban is that of plain living and high thinking.

Not Much Modernized

“Vrndavana does not require to be modernized because Krsna’s Vrndavana is a transcendental village. They completely depend on nature’s beauty and nature’s protection. The community in which Krsna preferred to belong was the vaisya (agricultural) community because Nanda Maharaja happened to be a vaisya king, or landholder, and his main business was cow protection. It is understood that he had 900,000 cows, and Krsna and Balarama used to take charge of them along with His many cowherd boy friends. Every day, in the morning, He used to go out with His friends and cows into the pasturing grounds. So, if you seriously want to convert this new spot into New Vrindaban, I shall advise you not to make it very much modernized. But as you are American boys, you must make it just suitable to your minimum needs. Nor should you make it too much luxurious as generally Europeans and Americans are accustomed. Better to live there without modern amenities and to live a natural healthy life for executing Krsna consciousness. It may be an ideal village where the residents will have plain living and high thinking. For plain living we must have sufficient land for raising crops, and pasturing grounds for the cows. If there are sufficient grains and production of milk, then the whole economic problem is solved. You do not require any machines, cinema, hotels, slaughterhouses, brothels, nightclubs-all these modern amenities. People in the spell of maya are trying to squeeze out gross pleasure from the senses, which is not possible to derive to our heart’s content. Therefore we are confused and baffled in our attempt to eschew eternal pleasure from gross matter. Actually, joyful life is on the spiritual platform; therefore we should try to save our valuable time from material activities and engage them in Krsna consciousness. But at the same time, because we have to keep our body and soul together to execute our mission, we must have sufficient (not extravagant) food to eat, and that will be supplied by grains, fruits and milk.

“The difficulty is that the people in this country want to continue their practice of sense gratification, and at the same time they want to become transcendentally advanced. This is quite contradictory. One can advance in transcendental life by the process of negating the general practice of materialistic life. The exact adjustment is in Vaisnava philosophy, which is called yukta-vairagya. This means that we should simply accept the bare necessities of our material part of life, and try at the same time for spiritual advancement. This should be the motto of New Vrindaban, if you at all develop it to the perfectional stage.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 6/14/68)

Regarding New Vrindaban’s cow protection program, Srila Prabhupada writes:

“We must have sufficient pasturing ground to feed the animals all year. We have to maintain the animals throughout their lives. We must not make any program for selling them to the slaughterhouses. That is the way of cow protection. Krsna by His practical example taught us to give all protection to the cows, and that should be the main business of New Vrindaban. Vrndavana is also known as Gokula. Gomeans cows, and kula means congregation. Therefore the special feature of New Vrindaban will be cow protection, and by doing so, we shall not be the losers. In India, of course, a cow is protected, and the cowherdsmen derive sufficient profit by such protection. Cow dung is used for fuel. Cow dung dried in the sunshine is kept in stock for utilization as fuel in the villages. They get wheat and other cereals produced from the field. There is milk and vegetables, and the fuel is cow dung, and thus they are self-sufficient, independent, in every village. There are hand weavers for the cloth. And the country oil-mill (consisting of a bull walking in a circle around two big grinding stones, attached with yoke) grinds the oil seeds into oil. The whole idea is that people residing in New Vrindaban may not have to search for work outside. Arrangements should be such that the residents will be self-satisfied. That will make an ideal asrama. I do not know whether these ideals can be given practical shape, but I think that people may be happy in any place with land and cow without endeavoring for so-called amenities of modern life which simply increase anxieties for maintenance and proper equipment. The less we are anxious for maintaining our body and soul together, the more we become favorable for advancing in Krsna consciousness.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 6/14/68)

Constructing Temples

As for the development of buildings, Srila Prabhupada has given specific instructions for temples and living quarters. At present New Vrindaban includes 133 acres (more land will be available in the future) of pasture, forest, ponds, waterfalls, mountains and streams, so there are varied settings for numerous buildings. Srila Prabhupada advises:

“Concentrate on one temple, and then we shall extend one after another. Immediately the scheme should be to have a temple in the center and residential quarters for the brahmacaris or grhasthassurrounding it. Let us go ahead with that plan at first.

“Also you will be pleased to note that I’ve asked Goursundar to make a layout of the whole land, and I shall place seven different temples in different situations, as prototype of Vrndavana. There will be seven principal temples, namely, Govinda, Gopinatha, Madana-Mohana, Syamasundara, Radha-Ramana, Radha-Damodara, and Gokulananda. Of course in Vrndavana there are about, more or less, big and small, 5,000 temples; that is a far distant scheme. But immediately we shall take up constructing at least seven temples in different places, meadows and hills. So I am trying to make a plan out of the description of the plot of our land. And the hilly portions may be named Govardhana. On Govardhana-side, the pasturing grounds for the cows may be alloted.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 8/23/68)

New Vrindaban is a means for the sincere participants to please the Spiritual Master by progress in Krsna consciousness, and when the Spiritual Master is pleased, Lord Krsna is pleased. Srila Prabhupada writes:

“Now we can work with great enthusiasm for constructing a New Vrindaban in the United States of America. People who came from Europe to this part of the world named so many new provinces, just like New England, New Amsterdam, New York, so I also came to this part of the world to preach Krsna consciousness, and by His grace and by your endeavor, New Vrindaban is being constructed. That is my great happiness. Our sincere endeavor in the service of the Lord, and the Lord’s assistants, to make our progressive march successful, are two important things to be followed in the spiritual advancement of life. I think it was Krsna’s desire that this New Vrindaban scheme should be taken up by us, and now He has given us a great opportunity to serve Him in this scheme. So let us do it sincerely, and all other help will come automatically. I am very glad to notice in Kirtanananda’s letter that he has realized more and more that the function of New Vrindaban is nothing physical or bodily, but purely spiritual and for the glorification of the Lord, Sri Hari. If we actually keep this view before us, certainly we shall be successful in our progressive march.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 8/23/68)

Another important project in New Vrindaban is the development of a school, grades one through twelve, where children from the urban centers can come to learn reading, writing, mathematics, the basic sciences and Krsna consciousness. At present children are being individually tutored, and official State approval is impending the construction of a schoolhouse to meet building regulations. “So you have now taken charge of the sunrise of New Vrindaban,” Srila Prabhupada writes. “Our program there is to construct seven temples. One, Rupanuga Vidyapitha, is to be a school for educating brahmanas and Vaisnavas. We have enough technological and other types of educational institutions; there are none where actual brahmanas and Vaisnavas are produced. So we will have to establish an educational institution for that purpose in New Vrindaban.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 1/12/68) As soon as buildings are constructed, the school program can be swiftly executed: “I am encouraged to know that you are very enthusiastic about our projects for developing New Vrindaban. So far as the school goes, we have many qualified teachers, and they are all enthusiastic about going there and beginning their teaching work. The only thing is that there is as of yet no place to accommodate these teachers. So as soon as these facilities are constructed, we can at once start at full force in setting up our Krsna consciousness school program.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 12/25/69)

In May and June, 1969, His Divine Grace Srila Prabhupada stayed in New Vrindaban for six weeks and gave specific directions for construction and general management. After his visit, he wrote: “I am always thinking of your New Vrindaban. The first thing I find is the taste of the milk. The milk which we are talking here is not at all comparable with New Vrindaban milk. Anyway, there must be a gulf of difference between city life and country life. As poet Cowper said, ‘Country is made by God, and city is made by man.’ Therefore my special request is that you should try to maintain as many cows as possible in your New Vrindaban. Regarding duties, the men should be engaged in producing vegetables, tilling the field, taking care of the animals, house construction, etc., and the women shall do the indoor activities: taking care of the children, keeping the temple and kitchen very clean, cooking and churning butter. If they cooperate with the boys, then surely very quickly New Vrindaban will develop as nicely as possible.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 6/24/69)

In August, 1970, New Vrindaban held its first annual Janmastami celebration, a three day celebration of Sri Krsna’s birth, and hundreds of devotees from as far away as Australia attended. Srila Prabhupada, who was in India at the time, sent a Janmastami message, exhorting those interested in transcendental communal living to complete developing New Vrindaban into a village “one mile long and one mile wide.” “Regarding Janmastami arrangement, it is going on nicely, and that is very encouraging. We have started New Vrindaban in America, and it must be finished in the American way. In Vrndavana there are so many temples, they say 5,000, or in Vrndavana every home, every cottage is a temple. As far as possible, try to develop New Vrindaban on this standard. In the coming meeting of Janmastami, amongst other business you must have a resolution to finish the development of New Vrindaban in the right sense of the term.” (Srila Prabhupada, Letter, 8/20/70)

2013 09 09 Jagannath Puri Yatra The Process of Rath Yatra Morning Lecture) Radhanath Swami

When things go wrong in our life, doubts may assail us: “I am trying to be a good person, a good devotee. Why isn’t Krishna doing anything to help me? Does he care? Does he even exist?”

How do we deal with such doubts?

By learning to give the benefit of doubt to Krishna.

Instead of assuming our way to be the right way and labeling all other ways as wrong, we stay open to the possibility that Krishna might have a better plan. After all, he is far more intelligent than us.

Arjuna exemplifies this attitude of giving Krishna the benefit of doubt in his question (04.04). Krishna had stated earlier (04.01) that he gave the essential message of the Gita to the sun god in the past. Arjuna found this incomprehensible, for Krishna was born after the sun god. But instead of skeptically rejecting Krishna’s statement, Arjuna humbly asks: “How am I to understand this?” Krishna answers (04.05) by expanding the framework of discussion to encompass a past life when that knowledge transfer occurred.

This expansive framework applies not just to Krishna’s words but also to his actions. His plan extends far beyond what we consider good contextually to include what is the best for us eternally.

By giving Krishna the benefit of doubt, we prevent the wall of resentment from building between us and him. Instead, we open the window of understanding, thereby letting him guide us in his own inimitable way. If we don’t let the changed circumstances stop us from serving Krishna faithfully and intelligently, gradually we realize that things have worked out far better than our plan. Then our doubts disappear, our faith strengthens – and we march confidently through life’s journey back to Krishna.

***

Arjuna said: The sun-god Vivasvan is senior by birth to You. How am I to understand that in the beginning You instructed this science to him?

A devotee of the Lord does not forget his devotional service and other favorable activities, even when he is in a most distressful condition.

From: Rahul

Lord Krishna says Always think of him while doing work also. According to my experience while working I only concentrate on work and I am finding it difficult to think of Krishna while doing work.So can you tell me a way where I can simultaneously think of Krishna constantly and also do my work properly.