Today is the auspicious disappearance day of Sri Madhavendra Puri, the grand spiritual master of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Madhavendra Puri’s disciple Isvara Puri was accepted by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu as His spiritual master. Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, as the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is Himself the origin of all knowledge—all perfect, Vedic knowledge—and He had no need to accept a spiritual master. But because He was playing the part of a devotee, to set the example for others He accepted a spiritual master. And He accepted Isvara Puri specifically because he came in the line of Madhavendra Puri and was most dear to him. Madhavendra Puri was the first to exhibit love of God in separation, specifically in the mood of the gopis in separation from Krishna after He left Vrindavan. So, Madhavendra Puri is a most important person in the history of our disciplic succession—and in the history of the world.

Today is the auspicious disappearance day of Sri Madhavendra Puri, the grand spiritual master of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Madhavendra Puri’s disciple Isvara Puri was accepted by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu as His spiritual master. Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, as the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is Himself the origin of all knowledge—all perfect, Vedic knowledge—and He had no need to accept a spiritual master. But because He was playing the part of a devotee, to set the example for others He accepted a spiritual master. And He accepted Isvara Puri specifically because he came in the line of Madhavendra Puri and was most dear to him. Madhavendra Puri was the first to exhibit love of God in separation, specifically in the mood of the gopis in separation from Krishna after He left Vrindavan. So, Madhavendra Puri is a most important person in the history of our disciplic succession—and in the history of the world.

We shall read from Sri Caitanya-caritamrta, Antya-lila, Chapter Eight: “Ramacandra Puri Criticizes the Lord.” Ramachandra Puri was a disciple of Madhavendra Puri and a godbrother of Isvara Puri, but he developed an offensive mentality toward his spiritual master, and as a result he became so fallen that he dared to criticize Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. We begin with the chapter summary:

“The following summary of the Eighth Chapter is given by Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura in his Amrta-pravaha-bhasya. This chapter describes the history of the Lord’s dealings with Ramacandra Puri. Although Ramacandra Puri was one of the disciples of Madhavendra Puri, he was influenced by dry Mayavadis, and therefore he criticized Madhavendra Puri. Therefore Madhavendra Puri accused him of being an offender and rejected him. Because Ramacandra Puri had been rejected by his spiritual master, he became concerned only with finding faults in others and advising them according to dry Mayavada philosophy. For this reason he was not very respectful to the Vaisnavas, and later he became so fallen that he began criticizing Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu for His eating. Hearing his criticisms, Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu reduced His eating, but after Ramacandra Puri left Jagannatha Puri, the Lord resumed His usual behavior.”

TEXT 1

tam vande krsna-caitanyam

ramacandra-puri-bhayat

laukikaharatah svam yo

bhiksannam samakocayat

TRANSLATION

Let me offer my respectful obeisances to Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who reduced His eating due to fear of the criticism of Ramacandra Puri.

TEXT 2

jaya jaya sri-caitanya karuna-sindhu-avatara

brahma-sivadika bhaje carana yanhara

TRANSLATION

All glories to Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, the incarnation of the ocean of mercy! His lotus feet are worshiped by demigods like Lord Brahma and Lord Siva.

TEXT 3

jaya jaya avadhuta-candra nityananda

jagat bandhila yenha diya prema-phanda

TRANSLATION

All glories to Nityananda Prabhu, the greatest of mendicants, who bound the entire world with a knot of ecstatic love for God!

TEXT 4

jaya jaya advaita isvara avatara

krsna avatari’ kaila jagat-nistara

TRANSLATION

All glories to Advaita Prabhu, the incarnation of the Supreme Personality of Godhead! He induced Krsna to descend and thus delivered the entire world.

TEXT 5

jaya jaya srivasadi yata bhakta-gana

sri-krsna-caitanya prabhu—yanra prana-dhana

TRANSLATION

All glories to all the devotees, headed by Srivasa Thakura! Sri Krsna Caitanya Mahaprabhu is their life and soul.

TEXT 6

ei-mata gauracandra nija-bhakta-sange

nilacale krida kare krsna-prema-tarange

TRANSLATION

Thus Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, at Jagannatha Puri, performed His various pastimes with His devotees in the waves of love for Krsna.

COMMENT by Giriraj Swami

The next verses describe Ramachandra Puri’s arrival in Jagannatha Puri. He came specifically to meet Paramananda Puri and Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. His policy was to invite Vaishnavas and feed them prasada and by various means induce them to eat more and more—and then criticize them for eating too much. Next, Srila Krishnadasa Kaviraja Gosvami, the author of Sri Caitanya-caritamrta, explains the history of Ramachandra Puri, which contains the story of the disappearance of Sri Madhavendra Puri.

TEXT 18

purve yabe madhavendra karena antardhana

ramacandra-puri tabe aila tanra sthana

TRANSLATION

Formerly, when Madhavendra Puri was at the last stage of his life, Ramacandra Puri came to where he was staying.

TEXT 19

puri-gosani kare krsna-nama-sankirtana

“mathura na painu’ bali” karena krandana

TRANSLATION

Madhavendra Puri was chanting the holy name of Krsna, and sometimes he would cry, “O my Lord, I did not get shelter at Mathura.”

TEXT 20

ramacandra-puri tabe upadese tanre

sisya hana guruke kahe, bhaya nahi kare

TRANSLATION

Then Ramacandra Puri was so foolish that he fearlessly dared to instruct his spiritual master.

TEXT 21

“tumi—purna-brahmananda, karaha smarana

brahmavit hana kene karaha rodana?”

TRANSLATION

“If you are in full transcendental bliss,” he said, “you should now remember only Brahman. Why are you crying?”

PURPORT by Srila Prabhupada

As stated in the Bhagavad-gita, brahma-bhutah prasannatma: a Brahman realized person is always happy. Na socati na kanksati: he neither laments nor aspires for anything. Not knowing why Madhavendra Puri was crying, Ramacandra Puri tried to become his advisor. Thus he committed a great offense, for a disciple should never try to instruct his spiritual master.

COMMENT

The scriptures contain many negative injunctions, such as the one we just read from the Gita: na socati na kanksati—one who is on the Brahman platform neither hankers nor laments. In the Upanishads negative statements are also used to describe the Lord, that the Lord has no name, no form, no qualities, no face, no hands, no legs. Srila Prabhupada explains that these negative statements mean that the Lord has no material hands or legs but that He has spiritual hands and legs. Similarly, instructions such as na socati na kanksati—one should not hanker or lament—mean that one should not hanker or lament materially, for material things. Madhavendra Puri was on the highest platform of love of God. He was feeling separation from Krishna, hankering to attain Krishna’s service and lamenting because he felt unable to do so. He was on the spiritual platform. But Ramachandra Puri, being influenced by impersonal philosophy, could not understand that the negative statements apply to material form and qualities, and material hankering and lamentation. He could not understand that his spiritual master was feeling separation from Krishna on the transcendental platform. And he was so audacious that he dared to advise his spiritual master, which was his downfall.

TEXT 22

suni’ madhavendra-mane krodha upajila

“dura, dura, papistha” bali’ bhartsana karila

TRANSLATION

Hearing this instruction, Madhavendra Puri, greatly angry, rebuked him by saying, “Get out, you sinful rascal!

PURPORT

Ramacandra Puri could not understand that his spiritual master, Madhavendra Puri, was feeling transcendental separation. His lamentation was not material. Rather, it proceeded from the highest stage of ecstatic love of Krsna. When he was crying in separation, “I could not achieve Krsna! I could not reach Mathura!” this was not ordinary material lamentation. Ramacandra Puri was not sufficiently expert to understand the feelings of Madhavendra Puri, but nevertheless he thought himself very advanced. Therefore, regarding Madhavendra Puri’s expressions as ordinary material lamentation, he advised him to remember Brahman, because he was latently an impersonalist. Madhavendra Puri understood Ramacandra Puri’s position as a great fool and therefore immediately rebuked him. Such a reprimand from the spiritual master is certainly for the betterment of the disciple.

COMMENT

Krodha upajila—when Madhavendra Puri heard the words of Ramachandra Puri, krodha, anger, arose in him. On the material platform, krodha is a no-no. Kama, krodha, lobha, moha, mada, and matsarya—lust, anger, greed, illusion, pride, and envy—are enemies of the conditioned soul and are considered gateways to hell. The Bhagavad-gita (3.37) explains,

kama esa krodha esa

rajo-guna-samudbhavah

mahasano maha-papma

viddhy enam iha vairinam

“Lust is born of contact with the material mode of passion and later transformed into wrath; it is the all-devouring sinful enemy of this world.” Lust and anger are products of the mode of passion, and they lead one to degradation. Yet here we read, krodha upajila—anger arose within Madhavendra Puri. But his was not any ordinary, material anger; it was transcendental. Material anger arises when one’s lust is frustrated (kamat krodho ’bhijayate). The Third Canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam uses the Sanskrit term kamanujena for anger. Literally, kama-anujena means “the younger brother of lust”—wherever the older brother goes, the younger brother follows. Wherever there is lust, anger follows. When our material desires become frustrated, we become angry. Spiritually, when there is an obstacle to devotional service, one may also become angry—not materially, but spiritually—and use that anger to remove the obstacle. From one point of view, Ramachandra Puri’s presence was an impediment to Madhavendra Puri’s meditation on Krishna, so Madhavendra Puri wanted him away. But on another level, Ramachandra Puri’s pride and tendency toward impersonalism were obstacles to his own spiritual advancement, and so his spiritual master rebuked him to purify him. As Srila Prabhupada notes, “Such a reprimand from the spiritual master is certainly for the benefit of the disciple.”

Vaisnavera kriya mudra vijneha na bujhaya: even the most learned scholar cannot understand the activities and characteristics of a transcendental Vaishnava. Therefore, we should be careful when we deal with Vaishnavas, lest we misunderstand them and offend them.

TEXT 23

“krsna na painu, na painu ‘mathura’

apana-duhkhe maron—ei dite aila jvala

TRANSLATION

“O my Lord Krsna, I could not reach You, nor could I reach Your abode, Mathura. I am dying in my unhappiness, and now this rascal has come to give me more pain.

TEXT 24

“more mukha na dekhabi tui, yao yathi-tathi

tore dekhi’ maile mora habe asad-gati

TRANSLATION

“Don’t show your face to me! Go anywhere else you like. If I die seeing your face, I shall not achieve the destination of my life.

TEXT 25

“krsna na painu muni maron apanara duhkhe

more ‘brahma’ upadese ei chara murkhe”

TRANSLATION

“I am dying without achieving the shelter of Krsna, and therefore I am greatly unhappy. Now this condemned foolish rascal has come to instruct me about Brahman.”

COMMENT

Generally, a spiritual master does not reject a disciple. Still, Krishna, in the Bhagavad-gita, says, ye yatha mam prapadyante tams tathaiva bhajamy aham: as people approach Me, I reciprocate accordingly. If someone neglects Krishna, Krishna will neglect him. The spiritual master is the representative of Krishna. Ramachandra Puri had in effect rejected Madhavendra Puri as his spiritual master, because how can a disciple advise his spiritual master so?

Of course, sometimes even Krishna consults. In Mathura and Dvaraka He would consult Uddhava, and Uddhava would advise Him in a humble mood of loving service. But Ramachandra Puri was not offering advice in a mood of humble service. Rather, he was proud and thought himself superior in transcendental knowledge even to his spiritual master. Therefore he dared to advise his spiritual master in the matter of Krishna consciousness. In effect, he rejected Madhavendra Puri as a spiritual master. He thought he was more advanced than him, that he was on the Brahman platform and that his spiritual master wasn’t. So he foolishly instructed his spiritual master to be fixed in Brahman.

One of the lessons here is that if a disciple gets too close to the spiritual master without having the required purity, he or she may mistake him to be ordinary and commit offenses. Srila Prabhupada never rejected a disciple—unless the disciple rejected him. One case was Prabhupada’s disciple Aravinda, who served for some time as Prabhupada’s personal servant but eventually left. Later he met a devotee who informed him that Srila Prabhupada was in town. “You should come and meet Srila Prabhupada,” the devotee told him.

So, Aravinda came, and when he saw Prabhupada he told him, “Krishna consciousness never really worked for me, so I left.” Indirectly, he was criticizing Srila Prabhupada and Krishna consciousness. And Srila Prabhupada replied, “Good, I am glad you left, because now I don’t have to look at your morose face anymore.” Reading this line—“Don’t show your face to me”—reminded me of Srila Prabhupada’s words. But it was tit for tat. Prabhupada would call the scientists and other critics fools and rascals because in their own way they were calling Krishna’s devotees fools and rascals. Aravinda said that he had tried Krishna consciousness for some time but that he hadn’t really gotten much from it. In effect, he was saying he didn’t really like Krishna consciousness or being around Srila Prabhupada. And Prabhupada was saying, “I am glad you left, because we didn’t really like having you around us.”

Ultimately, both the blessings and the curses of a Vaishnava are beneficial. Once, two sons of Kuvera (the treasurer of the demigods) were sporting naked with heavenly women in a celestial river. They were so intoxicated with their material opulence and prestige that when their spiritual master, Narada Muni, came upon them, they felt no shame and did not even cover themselves. And so Narada cursed them to take birth as trees. Srila Prabhupada said that trees stand naked and think themselves very beautiful, and that Krishna fulfills all desires: “Oh, you wanted to be naked, to expose your beauty? Okay, take birth as a tree; stand naked for a hundred years and display your beauty.” But Sri Narada’s curse was actually a blessing. He took advantage of the situation to show the young men special mercy by giving them a curse that would relieve them of their false pride and ultimately give them audience of Sri Krishna. And so they took birth as twin arjun trees in the courtyard of Mother Yasoda. Then, during His damodara-lila, to fulfill the desire of Narada, Krishna dragged a wooden grinding mortar between the two trees, uprooted them, and delivered the two demigods, saying,

jnatam mama puraivaitad

rsina karunatmana

yac chri-madandhayor vagbhir

vibhramso ’nugrahah krtah

“The great saint Narada Muni is very merciful. By his curse, he showed the greatest favor to both of you, who were mad after material opulence and who had thus become blind. Although you fell from the higher planet Svargaloka and became trees, you were most favored by him. I knew of all these incidents from the very beginning.” (SB 10.10.40)

Ramachandra Puri—at least initially—was quite unfortunate, as we shall read.

TEXT 26

ei ye sri-madhavendra sripada upeksa karila

sei aparadhe inhara ‘vasana’ janmila

TRANSLATION

Ramacandra Puri was thus denounced by Madhavendra Puri. Due to his offense, gradually material desire appeared within him.

PURPORT

The word vasana (“material desires”) refers to dry speculative knowledge. Such speculative knowledge is only material. As confirmed in Srimad-Bhagavatam (10.14.4), a person without devotional service who simply wants to know things (kevala-bodha-labdhaye) gains only dry speculative knowledge but no spiritual profit. This is confirmed in the Bhakti-sandarbha (111), wherein it is said:

jivan-mukta api punar yanti samsara-vasanam

yady acintya-maha-saktau bhagavaty aparadhinah

“Even though one is liberated in this life, if one offends the Supreme Personality of Godhead he falls down in the midst of material desires, of which dry speculation about spiritual realization is one.”

In his Laghu-tosani commentary on Srimad-Bhagavatam (10.2.32), Jiva Gosvami says:

jivan-mukta api punar bandhanam yanti karmabhih

yady acintya-maha-saktau bhagavaty aparadhinah

“Even if one is liberated in this life, he becomes addicted to material desires because of offenses to the Supreme Personality of Godhead.”

A similar quotation from one of the Puranas also appears in the Visnu-bhakti-candrodaya:

jivan-muktah prapadyante kvacit samsara-vasanam

yogino na vilipyante karmabhir bhagavat-parah

“Even liberated souls sometimes fall down to material desires, but those who fully engage in devotional service to the Supreme Personality of Godhead are not affected by such desires.”

These are references from authoritative revealed scriptures. If one becomes an offender to his spiritual master or the Supreme Personality of Godhead, he falls down to the material platform to merely speculate.

COMMENT

One effect of offenses is that one becomes influenced by material desires and sometimes is overwhelmed by them, and then, to justify one’s sinful activities, one may speculate and manufacture many excuses. Or one may develop an impersonal attitude. Yet another effect of offenses is that one becomes prone to commit more offenses, as explained in the next verse.

TEXT 27

suska-brahma-jnani, nahi krsnera ‘sambandha’

sarva loka ninda kare, nindate nirbandha

TRANSLATION

One who is attached to dry speculative knowledge has no relationship with Krsna. His occupation is criticizing Vaisnavas. Thus he is situated in criticism.

PURPORT

Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura has explained in his Anubhasya that the word nirbandha indicates that Ramacandra Puri had a steady desire to criticize others. Impersonalist Mayavadis, who have no relationship with Krsna, who cannot take to devotional service, and who simply engage in material arguments to understand Brahman, regard devotional service to Krsna as karma-kanda, or fruitive activities. According to them, devotional service to Krsna is but another means for attaining dharma, artha, kama, and moksa. Therefore they criticize the devotees for engaging in material activities. They think that devotional service is maya and that Krsna, or Visnu, is also maya. Therefore they are called Mayavadis. Such a mentality awakens in a person who is an offender to Krsna and His devotees.

COMMENT

Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu stated emphatically, mayavadi krsne aparadhi: “The Mayavadis are the greatest offenders to Lord Krishna.” Here we gain the further insight that they became Mayavadis as a result of offending Krishna. Because they committed offenses, they became impersonalists, Mayavadis, and as Mayavadis they committed more offenses and thus continued their degradation.

Now we come to the other example—that of a devoted disciple.

TEXT 28

isvara-puri gosani kare sripada-sevana

svahaste karena mala-mutradi marjana

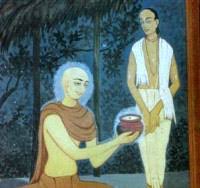

TRANSLATION

Isvara Puri, the spiritual master of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, performed service to Madhavendra Puri, cleaning up his stool and urine with his own hand.

TEXTS 29–31

Isvara Puri was always chanting the holy name and pastimes of Lord Krsna for Madhavendra Puri to hear. In this way he helped Madhavendra Puri remember the holy name and pastimes of Lord Krsna at the time of death.

Pleased with Isvara Puri, Madhavendra Puri embraced him and gave him the benediction that he would be a great devotee and lover of Krsna.

Thus Isvara Puri became like an ocean of ecstatic love for Krsna, whereas Ramacandra Puri became a dry speculator and a critic of everyone else.

TEXT 32

mahad-anugraha-nigrahera ‘saksi’ dui-jane

ei dui-dvare sikhaila jaga-jane

TRANSLATION

Isvara Puri received the blessing of Madhavendra Puri, whereas Ramacandra Puri received a rebuke from him. Therefore these two persons, Isvara Puri and Ramacandra Puri, are examples of the objects of a great personality’s benediction and punishment. Madhavendra Puri instructed the entire world by presenting these two examples.

COMMENT

It is stated that the dust of the lotus feet of a pure devotee is very powerful but that the same dust that elevates one to the highest level of Krishna consciousness, to the spiritual realm of Vrindavan, can also push one down to hell if one offends it. This principle was enunciated by Sati to her father Daksha after Daksha had offended Shiva, the greatest Vaishnava (vaisnavanam yatha sambhu), and the purport is relevant to the present discussion.

In Srimad-Bhagavatam, Canto Four, Chapter Four (“Sati Quits Her Body”), Text 13, Sati says:

nascaryam etad yad asatsu sarvada

mahad-vininda kunapatma-vadisu

sersyam mahapurusa-pada-pamsubhir

nirasta-tejahsu tad eva sobhanam

“It is not wonderful for persons who have accepted the transient material body as the self to engage always in deriding great souls. Such envy on the part of materialistic persons is very good because that is the way they fall down. They are diminished by the dust of the feet of great personalities.”

Srila Prabhupada explains in the purport, “Everything depends on the strength of the recipient. For example, due to the scorching sunshine many vegetables and flowers dry up, and many grow luxuriantly. Thus it is the recipient that causes growth and dwindling. Similarly, mahiyasam pada-rajo-’bhisekam: the dust of the lotus feet of great personalities offers all good to the recipient, but the same dust can also do harm. Those who are offenders at the lotus feet of a great personality dry up; their godly qualities diminish. A great soul may forgive offenses, but Krsna does not excuse offenses to the dust of that great soul’s feet, just as one can tolerate the scorching sunshine on one’s head but cannot tolerate the scorching sunshine on one’s feet.”

One must be especially careful when one comes close to a great soul. Rendering personal service unto a great soul, as Isvara Puri did to Madhavendra Puri, can bestow the greatest benefit, but if one is not pure enough and comes too close, one may commit offenses—and not just the accidental type. One may actually develop an offensive mentality toward the great soul and commit serious offenses that will cause one to go away and fall down.

In Sati’s statements about Lord Shiva we find a very surprising statement, that it is good that such envious persons commit offenses, because that way they fall down. How can a pure devotee who is a well-wisher of all living entities say that it is good for someone to commit offenses and fall down? Srila Prabhupada explains that the spiritual master, who is an ocean of mercy, will never reject a disciple, even when the disciple is fallen and causes pain to the spiritual master, but that Krishna, out of compassion for the spiritual master, out of His mercy, will cause the disciple to go away so that he does not cause more pain—even though the spiritual master himself does not reject the disciple. Of course, Krishna is the father of every living entity (aham bija-pradah pita) and the well-wisher of all (suhrdam sarva-bhutanam). He wants the ultimate benefit of everyone, but if one comes too close to the devotee or the Deity and out of familiarity develops misconceptions and an offensive mentality, it may be better if that person is removed from the situation and, being kept at a distance, gradually comes to his senses and redeems himself.

Now we come to Madhavendra Puri’s feelings of separation.

TEXT 33

jagad-guru madhavendra kari’ prema dana

ei sloka padi’ tenho kaila antardhana

TRANSLATION

His Divine Grace Madhavendra Puri, the spiritual master of the entire world, thus distributed ecstatic love for Krsna. While passing away from the material world, he chanted the following verse.

TEXT 34

ayi dina-dayardra natha he

mathura-natha kadavalokyase

hrdayam tvad-aloka-kataram

dayita bhramyati kim karomy aham

TRANSLATION

“O My Lord! O most merciful master! O master of Mathura! When shall I see You again? Because of My not seeing You, My agitated heart has become unsteady. O most beloved one, what shall I do now?”

TEXT 35

ei sloke krsna-prema kare upadesa

krsnera virahe bhaktera bhava-visesa

TRANSLATION

In this verse Madhavendra Puri teaches how to achieve ecstatic love for Krsna. By feeling separation from Krsna, one becomes spiritually situated.

TEXT 36

prthivite ropana kari’ gela premankura

sei premankurera vrksa-caitanya-thakura

TRANSLATION

Madhavendra Puri sowed the seed of ecstatic love for Krsna within this material world and then departed. That seed later became a great tree in the form of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu.

TEXT 37

prastave kahilun puri-gosanira niryana

yei iha sune, sei bada bhagyavan

TRANSLATION

I have incidentally described the passing away of Madhavendra Puri. Anyone who hears this must be considered very fortunate.

COMMENT

Having been blessed by hearing about the glorious passing of Sri Madhavendra Puri, we shall now discuss some of his earlier pastimes—and then return to the special verse that he uttered at the time of his passing from this world. Once, as described in Sri Caitanya-caritamrta, Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and Nityananda Prabhu and some of Their associates were traveling from Bengal to Orissa, to Jagannatha Puri. On the way, they visited a town called Remuna, where there is a Deity called Gopinatha. At the temple of Gopinatha, Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu narrated the story of Madhavendra Puri as He had heard it from His spiritual master, Isvara Puri.

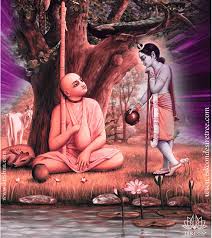

Earlier, when Madhavendra Puri came to Govardhana Hill, he had a dream in which the Deity Gopala appeared to him, took him by the hand, and led him to a place where He was hidden under a bush in the jungle at Govardhana. Then He instructed Madhavendra Puri to inform the villagers and to come take Him from the bush and install Him on Govardhana Hill. Madhavendra Puri followed the instructions of Gopala in the dream. He told the villagers, and they helped him cut through the thickets, discover the Deity, and take Him out of the ground. Then, as further directed by Gopala in the dream, Madhavendra Puri installed the Deity on top of Govardhana Hill. Devotees and brahmans bathed the Deity, chanted mantras, sang and danced, and offered garments, tulasi leaves, and flower garlands. Then they offered various kinds of food (bhoga), performed arati, and distributed massive, sumptuous prasada in a ceremony called Annakuta—just as it had been performed at the time of Lord Krishna during the Govardhana-puja.

For two years, devotees from all over the area came to see Gopala, present Him offerings, serve Him, worship Him, and celebrate the Annakuta ceremony, almost as it had been done on the first day. Then Gopala appeared to Madhavendra Puri again in a dream and told him that He was feeling very hot and that to cool Him and give Him relief, Madhavendra Puri should bring sandalwood from Jagannatha Puri and smear the pulp on His body. Madhavendra Puri took the instruction to heart, and after making all arrangements for the continued service of Gopala, he left by foot for Jagannatha Puri. On the way, in Bengal, in Shantipur, he met Advaita Acharya, who was so pleased to see his ecstatic love that he begged him for initiation. Thus Advaita Acharya was initiated in the line of Sri Madhavendra Puri. And further along the way, in Orissa, at Remuna, Madhavendra Puri saw the Deity Gopinatha.

Madhavendra Puri was so detached that he would never beg or ask for food. If someone offered him some food, he would eat a little. Otherwise, he would fast. He depended completely on the mercy of the Lord and made no effort to get food.

After Madhavendra Puri saw the beauty of Gopinatha in the temple, he went into the village marketplace, which was vacant, to sit and chant. That night, Gopinatha’s pujari had a dream in which the Deity told him that He had hidden a pot of sweet rice for Madhavendra Puri behind the curtains and that the pujari should find the sannyasi Madhavendra Puri in the marketplace and give him the pot of sweet rice. The pujari immediately awoke, bathed, went into the Deity room, and found the sweet rice, but he did not know exactly where Madhavendra Puri was. So he went into the vacant marketplace and called out, “Will the sannyasi named Madhavendra Puri please come and take his pot! The Deity Gopinatha has stolen this pot of sweet rice for you! You are the most fortunate person in all the three worlds!” Eventually Madhavendra Puri heard the call and came out, and the pujari gave him the sweet rice. But after relishing the prasada in ecstatic love, Madhavendra Puri considered that the next morning, when people heard that the Deity had delivered a pot of sweet rice to him, they would throng around him, and so he immediately departed for Jagannatha Puri. Madhavendra Puri was such a great devotee, so humble and fixed in his mood of service to Krishna, that he did not want any praise or popularity or attention. So he decided, “I must leave immediately.”

Even in Puri people understood that Madhavendra Puri was a great devotee, because whenever he would come before the Deity of Jagannatha, he would exhibit symptoms of ecstatic love of Godhead. Furthermore, they were aware of his transcendental reputation, and so they all came with love and devotion to offer him respects. Srila Krishnadasa Kaviraja Gosvami comments that the reputation of a devotee is so sublime that it follows him wherever he goes:

pratisthara bhaye puri gela palana

krsna-preme pratistha cale sange gadana

“Being afraid of his reputation [pratistha], Madhavendra Puri fled from Remuna. But the reputation brought by love of Godhead is so sublime that it goes along with the devotee, as if following him.” (Cc Madhya 4.147)

For his own sake, to avoid the crowds who came to honor him, Madhavendra Puri would have left Puri, but because he had come on a mission for Gopala, to get sandalwood and camphor, which were not easy to obtain but were available in Puri because they were used in the service of Lord Jagannatha, he remained. Yet even in Puri these items were very costly, and further, they were controlled by the government. Without a permit, one could not obtain or transport them. But when Madhavendra Puri told the local devotees about the history of Gopala and how He wanted sandalwood, they all came forward to help. They met people, got the permits, got sufficient quantities of sandalwood and camphor, and arranged a servant and expenses for Madhavendra Puri’s travels. And so he left, by foot, with his burden of sandalwood—his burden of love—back to Vrindavan, back to Govardhana.

On the way, after some days, Madhavendra Puri reached Remuna and again visited the temple of Gopinatha. And when the pujari saw him, he immediately brought him sweet rice prasada. That night in the temple, Madhavendra Puri had another dream. The Deity Gopala came to him and said, “There is no difference between My body and Gopinatha’s body. So if you smear the sandalwood pulp on the body of Gopinatha, My body will be cooled.” Sri Caitanya-caritamrta explains that the Deity of Gopala did not want Madhavendra Puri to have to suffer more by carrying such large amounts of sandalwood and camphor by foot in the hot sun and having to deal along the way with the Mohammedan officers, who would demand tolls and taxes and create trouble for travelers.

One could say that Madhavendra Puri passed Gopala’s test. Without any personal consideration or hesitation, he had acted with no interest other than to serve and please the Lord. And the Lord reciprocated. He was satisfied that Madhavendra Puri had come as far as Remuna, and He did not want his pure devotee to suffer any further. So Gopala instructed him to render the service to Gopinatha and that the service would be accepted by Gopala.

While narrating these pastimes, Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu extolled the glories of Srila Madhavendra Puri, and He asked Nityananda Prabhu, “Is there anyone in this world as fortunate as Madhavendra Puri?” Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu said (Cc Madhya 4):

TEXT 180

“hena-jana gopalera ajnamrta pana

sahasra krosa asi’ bule candana magina

“After receiving the transcendental orders of Gopala, this great personality traveled thousands of miles just to collect sandalwood by begging.

TEXT 181

“bhoke rahe, tabu anna magina na khaya

hena-jana candana-bhara vahi’ lana yaya

TRANSLATION

“Although Madhavendra Puri was hungry, he would not beg food to eat. This renounced person carried a load of sandalwood for the sake of Sri Gopala.

TEXT 182

“maneka candana, tola-viseka karpura

gopale paraiba’—ei ananda pracura

“Without considering his personal comforts, Madhavendra Puri carried one maund [about eighty-two pounds] of sandalwood and twenty tolas [about eight ounces] of camphor to smear over the body of Gopala. This transcendental pleasure was sufficient for him.

TEXT 183

“utkalera dani rakhe candana dekhina

tahan edaila raja-patra dekhana

TRANSLATION

“Since there were restrictions against taking the sandalwood out of the Orissa province, the toll official confiscated the stock, but Madhavendra Puri showed him the release papers given by the government and consequently escaped difficulties.

TEXT 184

“mleccha-desa dura patha, jagati apara

ke-mate candana niba-nahi e vicara

TRANSLATION

“Madhavendra Puri was not at all anxious during the long journey to Vrndavana through the provinces governed by the Muslims and filled with unlimited numbers of watchmen.

TEXT 185

“sange eka vata nahi ghati-dana dite

tathapi utsaha bada candana lana yaite

TRANSLATION

“Although Madhavendra Puri did not have a farthing with him, he was not afraid to pass by the toll officers. His only enjoyment was in carrying the load of sandalwood to Vrndavana for Gopala.

TEXT 186

“pragadha-premera ei svabhava-acara

nija-duhkha-vighnadira na kare vicara

TRANSLATION

“This is the natural result of intense love of Godhead. The devotee does not consider personal inconveniences or impediments. In all circumstances he wants to serve the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

TEXT 187

“ei tara gadha prema loke dekhaite

gopala tanre ajna dila candana anite

TRANSLATION

“Sri Gopala wanted to show how intensely Madhavendra Puri loved Krsna; therefore He asked him to go to Nilacala to fetch sandalwood and camphor.

TEXT 188

“bahu parisrame candana remuna anila

ananda badila mane, duhkha na ganila

TRANSLATION

“With great trouble and after much labor, Madhavendra Puri brought the load of sandalwood to Remuna. However, he was still very pleased; he discounted all the difficulties.

COMMENT

One might think that Madhavendra Puri made the endeavor and carried the burden because the Deity asked him but that it was such a hard labor that he must have really been exhausted and frustrated. But no, he was still happy. In fact, his pleasure increased (ananda badila). That is the nature of pure devotional service. The servant is happy, and his happiness increases. The same was said in relation to Govardhana Hill, the best of Lord Hari’s servants (hari-dasa-varyah).

hantayam adrir abala hari-dasa-varyo

yad rama-krsna-carana-sparasa-pramodah

manam tanoti saha-go-ganayos tayor yat

paniya-suyavasa-kandara-kandamulaih

“Of all the devotees, this Govardhana Hill is the best! O my friends, this hill supplies Krsna and Balarama, along with Their calves, cows, and cowherd friends, with all kinds of necessities—water for drinking, very soft grass, caves, fruits, flowers, and vegetables. In this way the hill offers respects to the Lord. Being touched by the lotus feet of Krsna and Balarama, Govardhana Hill appears very jubilant.” (SB 10.21.18)

Govardhana Hill was such a great servant that he offered his body for the service of the Lord and His devotees, who would step on him. He offered his grasses for the cows to eat. He offered his stones and caves as sitting and resting places. He offered his waters for drinking and washing. He offered his entire body for the service of the Lord. And he was jubilant (pramoda), being touched by the lotus feet of the Lord and His devotees. When a servant offers service in a mood of happiness, of jubilation, of pleasure, that gives more pleasure to the master, to the Lord. Naturally, if someone is happy to serve you, that makes you happy. If a service is offered out of duty—what to speak of begrudgingly—it is not as pleasing as when it is offered with genuine pleasure. Madhavendra Puri, in spite of taking so much trouble—traveling by foot, going through toll points, dealing with Muslim officers, enduring the heat and all the other impediments—was still in a very pleased mood (ananda badila) by the time he reached Remuna.

TEXT 189

pariksa karite gopala kaila ajna dana

pariksa kariya sese haila dayavan”

TRANSLATION

“To test the intense love of Madhavendra Puri, Gopala, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, ordered him to bring sandalwood from Nilacala, and when Madhavendra Puri passed this examination, the Lord became very merciful to him.”

COMMENT

In the course of Lord Chaitanya’s discussion of Madhavendra Puri, He came to quote the verse that Madhavendra Puri recited at the end of his life. Sri Caitanya-caritamrta tells us that this verse emanated directly from the mouth of Srimati Radharani and that only three people understood its deep meaning—Srimati Radharani, Sri Madhavendra Puri, and Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu Himself. Now we shall read more about what the Caitanya-caritamrta says about this verse (from Madhya-lila, Chapter Four: “Sri Madhavendra Puri’s Devotional Service”):

TEXTS 191–194

eta bali’ pade prabhu tanra krta sloka

yei sloka-candre jagat karyache aloka

ghasite ghasite yaiche malayaja-sara

gandha bade, taiche ei slokera vicara

ratna-gana-madhye yaiche kaustubha-mani

rasa-kavya-madhye taiche ei sloka gani

TRANSLATION

“. . . Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu read the famous verse of Madhavendra Puri. That verse is just like the moon. It has spread illumination all over the world.

“Continuous rubbing increases the aroma of Malaya sandalwood. Similarly, consideration of this verse increases one’s understanding of its importance.

“As the Kaustubha-mani is considered the most precious of valuable stones, this verse is similarly considered the best of poems dealing with the mellows of devotional service.

“Actually, this verse was spoken by Srimati Radharani Herself, and by Her mercy only was it manifest in the words of Madhavendra Puri.”

TEXT 195

kiba gauracandra iha kare asvadana

iha asvadite ara nahi cautha-jana

TRANSLATION

Only Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu has tasted the poetry of this verse. No fourth man is capable of understanding it.

PURPORT

This indicates that only Srimati Radharani, Madhavendra Puri, and Caitanya Mahaprabhu are capable of understanding the purport of this verse.

TEXT 196

sesa-kale ei sloka pathite pathite

siddhi-prapti haila purira slokera sahite

TRANSLATION

Madhavendra Puri recited this verse again and again at the end of his material existence. Thus uttering this verse, he attained the ultimate goal of life.

TEXT 197

ayi dina-dayardra natha he

mathura-natha kadavalokyase

hrdayam tvad-aloka-kataram

dayita bhramyati kim karomy aham

TRANSLATION

“O My Lord! O most merciful master! O master of Mathura! When shall I see You again? Because of My not seeing You, My agitated heart has become unsteady. O most beloved one, what shall I do now?”

PURPORT

The uncontaminated devotees who strictly depend on the Vedanta philosophy are divided into four sampradayas, or transcendental parties. Out of the four sampradayas, the Sri Madhvacarya-sampradaya was accepted by Madhavendra Puri. Thus he took sannyasa according to parampara, the disciplic succession. Beginning from Madhvacarya down to the spiritual master of Madhavendra Puri, the acarya named Laksmipati, there was no realization of devotional service in conjugal love. Sri Madhavendra Puri introduced the conception of conjugal love for the first time in the Madhvacarya-sampradaya, and this conclusion of the Madhvacarya-sampradaya was revealed by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu when He toured southern India and met the Tattvavadis, who supposedly belonged to the Madhvacarya-sampradaya.

When Sri Krsna left Vrndavana and accepted the kingdom of Mathura, Srimati Radharani, out of ecstatic feelings of separation, expressed how Krsna can be loved in separation. Thus devotional service in separation is central to this verse. Worship in separation is considered by the Gaudiya-Madhva-sampradaya to be the topmost level of devotional service. According to this conception, the devotee thinks of himself as very poor and neglected by the Lord. Thus he addresses the Lord as dina-dayardra natha, as did Madhavendra Puri. Such an ecstatic feeling is the highest form of devotional service. Because Krsna had gone to Mathura, Srimati Radharani was very much affected, and She expressed Herself thus: “My dear Lord, because of Your separation My mind has become overly agitated. Now tell Me, what can I do? I am very poor and You are very merciful, so kindly have compassion upon Me and let Me know when I shall see You.” Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu was always expressing the ecstatic emotions of Srimati Radharani that She exhibited when She saw Uddhava at Vrndavana. Similar feelings, experienced by Madhavendra Puri, are expressed in this verse. Therefore, Vaisnavas in the Gaudiya-Madhva-sampradaya say that the ecstatic feelings experienced by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu during His appearance came from Sri Madhavendra Puri through Isvara Puri. All the devotees in the line of the Gaudiya-Madhva-sampradaya accept these principles of devotional service.

COMMENT

This is a very deep topic—feeling separation from Krishna in the mood of Srimati Radharani and the gopis. We are certainly not qualified to discuss it. Still, following our acharyas, we shall try to say something to glorify Sri Madhavendra Puri on his disappearance day.

When Krishna left Vrindavan for Mathura, all the residents of Vrindavan were plunged into deep separation. The separation of the gopis was the most intense, because their attachment to Krishna was the most intense. None of the residents of Vrindavan had any interest in life other than Krishna and Krishna’s service. Still, comparatively, the gopis’ love for Krishna was the greatest. And among the gopis, Srimati Radharani’s love was the greatest. And that love reaches its most sublime heights in separation. In fact, the actual reason why Krishna left Vrindavan was to allow His devotees there to experience the highest ecstasy of love in separation and in that love to always relish His association. In their separation they actually meet Krishna, although externally they continue to express separation—even though internally they are relishing Krishna’s association.

The seed of this ecstatic mood was passed from Madhavendra Puri to his disciple Isvara Puri, who served him perfectly to the end, and from Isvara Puri to Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. And as Krishnadasa Kaviraja Gosvami says, that seed became a great tree in the person of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Therefore even fallen souls like us in Kali-yuga have been given access to this understanding and this process. It is inconceivable how people as fallen as we in Kali-yuga can be given access to this most highly confidential and exalted process.

Srila Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura gives the example of a king who becomes intoxicated, goes into his treasury, takes out his most valuable jewels, goes out on the street, and distributes the jewels to the beggars. They have no qualification, but the king, the owner of the jewels, is free to give the jewels to whomever he wishes. And in his intoxicated state, he distributes them without consideration. Similarly, Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, intoxicated with ecstatic love of God, is making these most precious gems available even to the most destitute of beggars. In Srila Rupa Gosvami’s words (Sri Upadesamrta 4), dadati pratigrhnati—Lord Chaitanya is giving (dadati), and it is our prerogative to accept (pratigrhnati).

This confidential verse spoken by Madhavendra Puri could be misunderstood—not in the gross way of Ramachandra Puri, who thought that Madhavendra Puri was absorbed in mundane lamentation when he should have been fixed in spiritual consciousness, but in a more subtle way. One may misunderstand and imagine that Madhavendra Puri wanted to see Krishna out of some selfish desire, but that, of course, was not the case. The truth is that Srimati Radharani and the gopis know that Krishna cannot really be happy without them; He cannot enjoy the same happiness with others as He does with them in Vrindavan. Therefore the young gopis want to see Him again not for their own happiness but for Krishna’s happiness, so they can please Him as only they can. Their love is completely pure—spotlessly pure. That same pure love was exhibited by Madhavendra Puri when he went to Jagannatha Puri to get sandalwood and camphor for Gopala without any consideration of personal gain or loss, pleasure or pain. And it was expressed by him in this verse. When the gopis say that they want to be with Krishna, it is not for their own happiness but to give Krishna happiness. Srila Krishnadasa Kaviraja Gosvami explains that although the gopis’ feelings appear to be lust, they are not; they are actually pure love. Lust (kama) is the desire for one’s own happiness, one’s own sense gratification, whereas pure love is the desire for Krishna’s happiness, Krishna’s satisfaction. Although superficially lust and love may resemble each other, intrinsically there is a great difference between them. Although iron and gold are both metals and thus have much in common, there is a vast difference between the value of gold and that of iron.

kama, prema,—donhakara vibhinna laksana

lauha ara hema yaiche svarupe vilaksana

“Lust and love have different characteristics, just as iron and gold have different natures.

atmendriya-priti-vancha-tare bali ‘kama’

krsnendriya-priti-iccha dhare ‘prema’ nama

“The desire to gratify one’s own senses is kama [lust], but the desire to please the senses of Lord Krsna is prema [love].” (Cc Adi 4.164–165)

Although sometimes the gopis pray to Krishna, “Please appear before us and satisfy our lusty desires,” that is their indirect way of speaking (paroksa-vada). Srila Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura explains why the gopis speak as if they were lusty for Krishna, when all scriptures state that their love is completely pure. One reason he gives is that if someone expresses his or her love openly, it decreases. He gives the example that if one keeps a lamp within one’s house, it will burn bright and strong, but if one puts it outside, it will waver and may even be extinguished. When one’s confidential feelings of love are kept within one’s heart, they increase, and if they are expressed openly, they decrease. That is the special feature of parakiya-rasa, that one’s loving feelings are kept inside.

Another reason is that in pure love one does not want the beloved to take any trouble, especially for oneself. Visvanatha Cakravarti gives the example that if you are hungry and visit someone, although you want to eat, if your friend asks, “Do you want some prasada?” you might say, “No, I am all right,” because out of love you don’t want your friend to take trouble. So the friend, knowing that you are hungry, won’t ask if you want him to prepare prasada for you, because he knows that you won’t want him to take trouble. Instead, he’ll say, “Actually, I’m just about to cook an offering for my Deities. Please wait.” Then he’ll cook and offer the food to the Deities and give you the prasada. In the same way, if the gopis were to say openly, in a direct way, “Krishna, we know that You are missing us, so we will come to be with You,” Krishna would say, “No, don’t take trouble for Me. I am fine as I am.” So instead of suggesting that Krishna wants them, they say that they want Krishna: “Please come back. We are burning in the fire of separation—in the fire of lusty desires. Please come back and fulfill our desires.” Thus, for example, the gopis say to Krishna (SB 10.31.7):

pranata-dehinam papa-karsanam

trna-caranugam sri-niketanam

phani-phanarpitam te padambujam

krnu kucesu nah krndhi hrc-chayam

“Your lotus feet destroy the past sins of all embodied souls who surrender to them. Those feet follow after the cows in the pastures and are the eternal abode of the goddess of fortune. Since You once put those feet on the hoods of the great serpent Kaliya, please place them upon our breasts and tear away the lust in our hearts.” But their actual intention is completely pure—to serve Krishna and please Him.

These are the intricate dealings of love on the platform of pure devotional service. By the mercy of Sri Madhavendra Puri first and then from him the disciplic succession—Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and His followers, the Gosvamis; and later Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, and our Srila Prabhupada—these very confidential moods have been explained for us so that we can come to appreciate them and hanker for them. It is a most special gift.

Devotees have asked, “Why did Srila Prabhupada take so much trouble to preach? Love of God is there in every bona fide scripture, and every bona fide process of religion can lead one to love God. There are examples of practitioners in different traditions who have developed love for God, so why all this effort, why all this sacrifice, specifically for Krishna consciousness?” The real reason is to give this love of Krishna in Vrindavan, especially in the mood of separation. This love is not available anywhere else. Although on the absolute platform all love of God is transcendental—even the love of the servants of Lord Narayana who worship Him in opulence in Vaikuntha—the greatest ecstasy is experienced in the pure love (kevala-bhakti) of Vrindavan, which is incomparable. Therefore, although this love is very confidential, Srila Prabhupada exerted this superhuman effort to induce the fallen souls to take to Krishna consciousness, so that ultimately they—we—could receive this most valuable, priceless, precious treasure. And all this is coming to us through disciplic succession by the grace of Sri Madhavendra Puri, whose disappearance day is today.

Hare Krishna.

[A talk by Giriraj Swami on Madhavendra Puri’s disappearance day, March 18, 2008, Houston]

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer Today is the auspicious disappearance day of Sri Madhavendra Puri, the grand spiritual master of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Madhavendra Puri’s disciple Isvara Puri was accepted by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu as His spiritual master. Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, as the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is Himself the origin of all knowledge—all perfect, Vedic knowledge—and He had no need to accept a spiritual master. But because He was playing the part of a devotee, to set the example for others He accepted a spiritual master. And He accepted Isvara Puri specifically because he came in the line of Madhavendra Puri and was most dear to him. Madhavendra Puri was the first to exhibit love of God in separation, specifically in the mood of the gopis in separation from Krishna after He left Vrindavan. So, Madhavendra Puri is a most important person in the history of our disciplic succession—and in the history of the world.

Today is the auspicious disappearance day of Sri Madhavendra Puri, the grand spiritual master of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Madhavendra Puri’s disciple Isvara Puri was accepted by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu as His spiritual master. Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, as the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is Himself the origin of all knowledge—all perfect, Vedic knowledge—and He had no need to accept a spiritual master. But because He was playing the part of a devotee, to set the example for others He accepted a spiritual master. And He accepted Isvara Puri specifically because he came in the line of Madhavendra Puri and was most dear to him. Madhavendra Puri was the first to exhibit love of God in separation, specifically in the mood of the gopis in separation from Krishna after He left Vrindavan. So, Madhavendra Puri is a most important person in the history of our disciplic succession—and in the history of the world. By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Praghosa Das

By Praghosa Das By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer By Vijaya Das

By Vijaya Das By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer Today is the disappearance day of Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja.

Today is the disappearance day of Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja. By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer Today is Shiva-ratri. Vaishnavas generally do not celebrate Shiva-ratri, and to begin, I will explain why, with reference to the Bhagavad-gita. We read from Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Chapter 7: “Knowledge of the Absolute”:

Today is Shiva-ratri. Vaishnavas generally do not celebrate Shiva-ratri, and to begin, I will explain why, with reference to the Bhagavad-gita. We read from Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Chapter 7: “Knowledge of the Absolute”: By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer