Announcing Our New Sankirtan Podcast: A Journey of Devotion and Joy

Divine Connections: Global Visits and Spiritual Growth at ISKCON! March 5

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff WriterThe mercy of Gaura Nitai by Candramauli Swami. Navadwip Mandal Parikrama 2025 Day 3. Radhadesh reception hall ready to welcome thousands of visitors. Ambassadors from the Group of Latin America and the Caribbean (GRULAC) countries visited Iskcon Delhi. HG Padmapani Prabhu ACBSP departed. Gurudas: The Swami, The Beatles, and Stolen Butter. What about some Bharva Karela Sabzi? Lord Śiva is the greatest Vaishnava. Navadwip Mandal Parikrama 2025 Day 4. A Global Gathering for Lord Narsimha’s Appearance in the TOVP. Manor. Mantra. Music. February Sankirtan Scores Are Out! Harinama Cintamani Seminar – HH Bhanu Swami. Remembering Tamal Krishna Goswami. Unveiling ISKCON's Vision for Sustainable Cow Protection and Agriculture. Continue reading "Divine Connections: Global Visits and Spiritual Growth at ISKCON! March 5

→ Dandavats"

Living in His Shadow: Remembering Tamal Krishna Goswami

→ Dandavats

Read More...

Unveiling ISKCON’s Vision for Sustainable Cow Protection and Agriculture at the Bhumi Pujan of ISKCON Temple, Bhopal

→ Dandavats

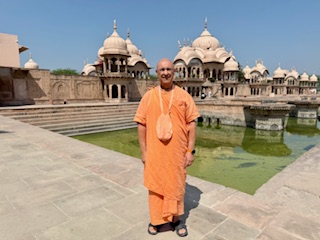

Govardhana Visit

→ Ramai Swami

After Kurukshetra we made our way back to Delhi and then on to Govardhana for a tour of the holy places in the area. I hadn’t visited in many years so it was our great fortune to again have the opportunity.

We first stopped off at a temple that was recently acquired by HH Navayogendra Swami near Kusuma Sarova. The devotees greeted us affectionately and later provided sumptuous lunch prasadam.

Of course, we took darshan of wonderful places like Manasi Ganga, Radha Kunda, Shyama Kunda and others but needed to head back to Delhi soon after. I look forward to the next visit.

Daily Spiritual Highlights: ISKCON’s Messages and Missions! March 4

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff WriterThe Lord is Unlimited – HH Bhanu Swami. Lord Siva is not an ordinary living entity. Two Essential Keys To Increase Our Attraction To Sri Krishna. Human form of life. My Arjuna Moment. Srila Prabhupada book distribution in different parts of Bangkok. Surabhi Das: “…and then gave me my name. He said, “Your name is Zorro”! Spiritual Unity Through Chanting and Community. Bhakti, Leadership, and Srila Prabhupada's Legacy. Bhaktivedanta Manor Presents: Morning Class with HH Radhanath Swami. Urban Devi: Jahnavi Harrison - Into the Forest - A Creative Journey. Continue reading "Daily Spiritual Highlights: ISKCON’s Messages and Missions! March 4

→ Dandavats"

Spreading Krishna’s Message: ISKCON’s Daily Highlights! March 3

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff WriterH. G. Daivishakti Mataji - Srila Prabhupada Lilamrita. Srimad Bhagavatam - HG Prithu Prabhu. Srimad Bhagavatam - HG Hansarupa Prabhu. Purushottama Dasa Thakura - Appearance. Navadwip Mandal Parikrama 2025 Day 2. SB 3.6.29 - HH BHAKTI PRABHAVA SWAMI. January 2025 - North American Sankirtan Newsletter. Supporting Hindu Mandirs in Suriname: Government Initiative Shares Resources, Including Bhagavad-gitas. Saturday Night Harinam in Central London. ISKCON Dallas / HG Prabhupada Priya Devi Dasi. 2nd Mar. '25 H. H. Radhanath Swami - Sacrifice, Maturity & Humanity of Uddhava. HH Bhakti Marga Swami visits Sri Mayapur Community Hospital. Step Inside History: Prabhupada Legacy Museum Tour with Kalakantha Prabhu. Facing reversals - Devakinandan Das. ATL 2025-02-22 Pundarika Vidyanidhi dasa Continue reading "Spreading Krishna’s Message: ISKCON’s Daily Highlights! March 3

→ Dandavats"

Celebrating ISKCON’s Global Impact: Festivals, Teachings, and Devotee Empowerment Today! March 2

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff WriterAcyuta, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Free Write Journal. Kasyapa Muni: This particular time is most inauspicious. The Man in the Machine. "I do not have to pay?". The genius of Srila Prabhupada. ISKCON Mauritius Reaches Key Milestone to Open 5-Star Vegetarian Restaurant. Navadwip Mandal Parikrama 2025 Day 1. Touching Krishna's Words: Bringing the Bhagavad-gita to the Visually Impaired. Maha Harinama in Venice - Italy. Here We Go Again! - Rishikesh Kirtan Fest. ATL 2025-02-18 Akuti devi dasi. Darshan of Sri Sri Radha Madan Mohanji in Karauli (photos). "I can tell all the foolish people that I am not Krishna - that much power Krishna has given me." There Is Nothing Else To Have In The 14 Worlds Except The Holy Names. Continue reading "Celebrating ISKCON’s Global Impact: Festivals, Teachings, and Devotee Empowerment Today! March 2

→ Dandavats"

The Divine Journey Begins!

→ Mayapur.com

Visit to Kurukshetra

→ Ramai Swami

After visiting our Iskcon Jyotisar temple, we went for a tour of some of the holy sites at Kurukshetra. Of course, the most important was the holy place where Lord Krishna spoke Bhagavad-gita to Arjuna five thousand years ago.

With the help of the Government, the area has built up tremendously since my last visit. There is a lake with a light show and a big museum depicting various pastimes. We also went to Brahma Sarovara, where Lord Brahma performed yajna and Bhisma Kunda, where Bhisma was felled by the arrows of Arjuna.

Glorious ISKCON Events and Teachings Uplift Devotees Today! March 1

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff WriterH.G. Guru Prasad Swami || Srimad Bhagavatam. ISKCON Mayapur Kirtan Mela 2025 Day - 5. Srimad Bhagavatam - HG Krishnadas Kaviraj Prabhu. Navadwip Mandala Parikrama Adhivas in Yogapith 2025. Sadhus take the responsible task of speaking about the naked truth of material existence! Mayapur Kirtan Mela 2025 Day 4 - (photos). Wealth vs. Wisdom: The Blindness of Opulence. Srimad-Bhagavatam Class by HG Sankarshan Das Prabhu. Spiritual Wisdom and Sustainable Farming Insights. Navadwip Mandal Parikrama 2025 - Adhivas Ceremony. Srimad-Bhagavatam Class by HH Dhirashanta Swami. Iskcon devotees with Aditya Yogi Nath. New musical video by Madhava's Band. "Duty and Lamentation" with Ekendra Prabhu. CC Madhya 1.52-56 by HH Janananda Swami. Saranagati Retreat Closing. H. G. Chaitanya Charan Prabhu SB 3.4.27 ISKCON Chowpatty Continue reading "Glorious ISKCON Events and Teachings Uplift Devotees Today! March 1

→ Dandavats"

Using Imagination in Bhakti: Why? How? | Bhagavatam 3.4.27 | Chowpatty, Mumbai – Chaitanya Charan

→ The Spiritual Scientist

Dedication in bhakti – Chaitanya Charan 28 2 2025 – Prayag

→ The Spiritual Scientist

The post Dedication in bhakti – Chaitanya Charan 28 2 2025 – Prayag appeared first on The Spiritual Scientist.

Decisions Determine destiny – Chaitanya Charan 27 02 2025 – Varanasi

→ The Spiritual Scientist

The post Decisions Determine destiny – Chaitanya Charan 27 02 2025 – Varanasi appeared first on The Spiritual Scientist.

Travel Journal#21.8: Tallahassee and Alachua

→ Travel Adventures of a Krishna Monk

Diary of a Traveling Sadhaka, Vol. 21, No. 8

By Krishna Kripa Das

(Week 8: February 19–25, 2025)

(Sent from Tallahassee, Florida, on March 1, 2025)

Where I Went and What I Did

For the eighth week of 2025, I remained living at ISKCON Tallahassee and chanted three hours each day on Landis Green, behind the main Florida State University library.

On Friday Ananga Mohan Prabhu and a student guitar player joined me for an hour. During the week, I distributed four “On Chanting Hare Krishna” pamphlets along with forty-five little cups of halava to promote our Krishna Lunch at the campus.

The rose a student gave me on Valentine’s Day and which I used to decorate Gaura-Nitai’s altar, still looked wonderful after a week.

Even after eleven days, it remained in good condition.

Michelle, a neuroscience major, recommended that I make a sign advertising the free dessert, and I did. The first day I used the sign, I distributed the twelve little cups of halava I brought out in an hour and forty minutes instead of in three hours!

I went to the Sunday feast in Alachua and gave the Bhagavatam class on Monday morning there. You can hear it here. I mentioned how the pregnancy of Diti in the evening could have been avoided if the couple had a nice spiritual program in the evening as Srila Prabhupada recommended, and I discussed transcending lust. I also talked about Isvara Puri as it was his disappearance day.

I share lots of quotes from the books, lectures, conversations, and letters of Srila Prabhupada, many I read in Bhakti Vikasa Swami’s soon-to-be-published book on the mood and mission of Srila Prabhupada. I am trying to read all the Prabhupada biographies, and thus I share quotes from Miracle on Second Avenue by Mukunda Goswami. I share quotes from The Final Frontier, the latest book of Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami, which is in the production stage. I share quotes from the Golden Avatar by Yogesvara Prabhu, also in production. I share notes on talks by Hridayananda Goswami, Bhaktivedanta Nemi Maharaja, Drutakarma Prabhu, and Murli Gopal Prabhu at the January 2025 human evolution conference of the Bhaktivedanta Institute for Higher Studies in Gainesville. I share notes on classes by Nanda Dasi in Alachua and Govinda Kaviraja and Gaurachand Prabhus here in Tallahassee.

Thanks to Sakshi Gopal Prabhu for his kind donation. Thanks to Ananga Mohan Prabhu for giving me a ride to Alachua. Thanks to Pran Govinda Swami for allowing me to stay in his ashram in Alachua and for arranging for me to give Bhagavatam class at the temple there.

Itinerary

January 6–April 11: Tallahassee harinamas and FSU college outreach

– March 9–16: Krishna House Gainesville harinamas and UF college outreach

– March 15: Daytona Beach Ratha-yatra

April 12: St. Augustine Ratha-yatra

April 13: Gainesville harinama

April 14–15: USF harinamas in Tampa

April 16–20: Washington, D.C., harinamas with Sankarsana Prabhu

April 21–22: NYC Harinam

April 23: Flight to Brussels with a layover in Oslo

April 24–25: Kadamba Kanana Swami Vyasa-puja at Radhadesh

April 26: King’s Day harinama in Amsterdam

April 27: Liege harinama

April 28–May 1: Paris harinamas

May 2: Sarcelles market harinama and Amsterdam harinama

May 3–4: Holland Kirtan Mela and Sacinandana Swami seminar

May 5 and 6: harinama in Amsterdam, Antwerp, or Brussels

May 7: Flight from Brussels to New York City

May 8–June 15: NYC Harinam

mid June–mid August: Paris

– June 22: Paris Ratha-yatra

– July 4: Amsterdam harinama

– July 5: Amsterdam Ratha-yatra

Chanting Hare Krishna in Tallahassee

Govinda Kaviraja Prabhu chants Hare Krishna at a home program in Tallahassee (https://youtu.be/vf2ijd_ijWw):

Bhakti chants Hare Krishna at a home program in Tallahassee (https://youtu.be/bwmON7B_yhA):

Bhakti chants Hare Krishna during the arati there (https://youtube.com/shorts/IjJSgQMq__Y?feature=share):

Chanting Hare Krishna in Alachua

Godruma Prabhu chants Hare Krishna in Alachua during Sunday feast kirtan (https://youtu.be/MFIPvIp5tZM):

Maya Cabrinha chants Hare Krishna in Alachua after the Sunday feast (https://youtube.com/shorts/D_o5Kaqwr6k?feature=share):

Next, one son of Ekadasi Vrata Devi Dasi, Kishor Gopal Prabhu, led the Hare Krishna chant, accompanied by another, Ananta Govinda Prabhu, on the drum (https://youtube.com/shorts/u0R-aoEhNqk):

Insights

Srila Prabhupada:

From Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.5.16, purport:

“Expert devotees can also discover novel ways and means to convert the nondevotees in terms of particular time and circumstance.”

From Srimad-Bhagavatam 4.28.48, purport:

“The main business of human society is to think of the Supreme Personality of Godhead at all times, to become His devotees, to worship the Supreme Lord, and to bow down before Him. The acarya, the authorized representative of the Supreme Lord, establishes these principles, but when he disappears, things once again become disordered. The perfect disciples of the acarya try to relieve the situation by sincerely following the instructions of the spiritual master.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 13:

“In the Eleventh Canto, Twentieth Chapter, verse 9, of Srimad-Bhagavatam, the Lord Himself says, ‘One should execute the prescribed duties of varna and asrama as long as he has not developed spontaneous attachment for hearing about My pastimes and activities.’”

From Science of Self-Realization, Chapter 3:

“One has to learn by the result (phalena pariciyate). Our students are ordered to act like this, and they are not falling down. That they are remaining on the platform of pure spiritual life without hankering to culture the principles of avidya, or sense gratification, is the test of their proper understanding of the Vedas. They do not come back to the material platform, because they are relishing the nectarian fruit of love of God.”

From Dharma: The Way of Transcendence, Chapter 3:

“We are trying to render our humble service to human society by teaching, ‘You are attempting to become happy in so many ways, but instead of becoming happy you are becoming frustrated. So please take this Krishna consciousness and you will actually become happy.’ Imparting this knowledge is our mission.

From a conversation in Indore on December 5, 1970:

“So our mission is very grave and it should be act[ed] sincerely and then we get power from Krishna. If we act sincerely as representative[s] of Krishna then we will feel His power.”

From a letter to students [in San Francisco] on August 2, 1967:

“Never think that I am absent from you. Physical presence is not essential; presence by message (or hearing) is real touch. Lord Krishna is present by His message which was delivered 5,000 years ago. We feel always the presence of our past Acaryas simply by their immutable instructions.”

From a letter to Tamala Krishna Goswami on September 19, 1969:

“My desire is an open secret. I simply want all over the Western countries people may take this simple formula of chanting, dancing and eating Krishna Prasadam, and being happy. I am simply surprised that they should not accept this simple formula and be happy themselves. My only desire is that all people become happy and prosperous in Krishna Consciousness.”

From a letter to Jadurani from Srila Prabhupada’s servant, Paramahansa Swami, on January 3, 1975:

“Because I instruct one person one way, does that mean it is for everybody?”

From a letter to the devotees in New York on January 19, 1967:

“I understand that you are feeling my absence. Krishna will give you strength. Physical presence is immaterial; presence of the transcendental sound received from the spiritual master should be the guidance of life. That will make our spiritual life successful.”

From a letter to Govinda Dasi on August 17, 1969:

“You write that you have a desire to avail of my association again, but why do you forget that you are always in association with me? When you are helping my missionary activities, I am always thinking of you and you are always thinking of me. That is real association.”

From a remembrance of Tamal Krishna Goswami quoted by Madri Devi Dasi:

“My books are better than me, because the best of me is in the books. I sit there, and every word that comes out is the very best of me.”

From a letter to Brahmananda on September 28, 1969:

“I shall request you not to circulate all my letters that I address to you. Letters are sometimes personal and confidential, and if all letters are circulated, it may react reversely. I have already got some hints like that with letters I sent to you regarding Kirtanananda and Hayagriva. So in the future please do not circulate my letters to you. All my letters to you should be considered as confidential, and if you want at all to circulate, you just ask me before doing so.”

From a letter to Hansadutta on October 1, 1974:

“Your statement expressing your surrender to your spiritual master is proper. If this principle is followed you will remain pure and always protected by Krishna. Always follow my instructions and my example. This should be your life and soul.”

Mukunda Goswami:

From Miracle on Second Avenue:

“‘How are you feeling, Swami?’ I asked.

“He continued to chant softly, gazing at the somewhat primitive painting of Radha and Krishna on the wall to his right painted by a devotee artist. I thought maybe he hadn’t heard me, but after a few minutes he put down his beads and stood up.

“‘What is this body?’ he said, making a gesture with his palms open and his arms outstretched. He looked almost disgusted to inhabit an ephemeral body and incredulous that I would be concerned to inquire about the state of something so fleeting. I realized that although I had read about the temporary nature of the body and the eternality of the spirit soul, he was actually living that philosophy.

“For him the material world was not as important as the spiritual world, and he didn’t really care about his body coming to an end.”

“The parade moved forward once again with the generator roaring away on the floor of the truck. I climbed on the flatbed again and began to lead the chanting. The truck drove slowly down the street and the devotees walked beside it, chanting and smiling and waving to onlookers. Two barefoot young women I’d never seen before danced along the street in front of the truck, twirling and clapping with their eyes closed. The sound of my voice wafted over the buildings, ‘Hare Krishna Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna Hare Hare, Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare.’”

“‘Everyone was chanting and dancing in front of the truck,’ Malati said. ‘We walked all the way to the beach, and then everyone went back to the temple for a big feast!’

“‘At one point we thought the truck was going to roll backwards over the crowd,’ Gurudas said. ‘The engine stalled.’

“The Swami opened his eyes wide. ‘Yes, this is also happening in Puri,’ he said. ‘Lord Jagannatha’s cart sometimes stops and even rolls backwards! So this stoppage was the Lord’s mercy. This first American Rathayatra was real Rathayatra, just as in Puri.’”

“Shyamasundar came forward to tell him the news he and Malati had received the day before. ‘Swami, we won’t see you for a while now, maybe not even when you come back to America,’ he said.

“‘Oh? Why is that?’ the Swami asked. ‘Me and Malati, we have to go to jail.’

“The Swami looked a little surprised, but he gave a small smile. ‘That’s all right,’ he said. ‘Krishna was born in jail! His uncle Kamsa imprisoned his mother and father.’ He paused. ‘Why?’ he asked. ‘What did you do?’

“‘Well, it was before we were devotees,’ Shyamasundar said. ‘We were selling some drugs and we got caught. Drug dealing.’

“‘Never mind, I was also drug dealer,’ the Swami said. He chuckled softly.

“‘Yes, but these drugs weren’t legal pharmaceuticals like yours,’ Malati said, laughing in spite of herself.

“‘You must chant Hare Krishna as much as possible while you are there,’ he instructed.

They nodded. ‘We will.’”

Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami:

From The Final Frontier:

“I am getting up extra-early

just so I can write about Krishna

while I still have my wits.

Krishna is the be-all and see-all.

He is my favorite person.

He is worth getting up early for.”

“I get up early at any cost

just to be with Him.

Early in the morning,

with my dearmost one.

Get up early in the morning

just to be with Him.

He is worth rising early for.

He is my dearmost one.

I wish I could speak to Him

in sweetest tones.

I wish I could.

Krishna is the summum bonum.

“Krishna is worth getting up early just to be with Him,

just to share His sweetness

at the earliest possible hour.

Krishna is worth rising at the earliest hour

and making the sacrifice of being with Him.

Krishna is worth playing with and begging for.

He is the greatest treasure,

and rising early to meet with Him

is worth the highest price.

I speak my humble words

just to be with Lord Krishna.

“Krishna loves it when I rise for Him

and show my devotion.

My words to Him

come from my heart

and He is grateful to me.

“Yes, Krishna is happy that His cela rises early

and sings a hymn

that he pays for with all his devotion.

Krishna appreciates that a devotee

speaks from his heart.

Krishna appreciates that His cela

may not be so smart.

But the Lord reciprocates

with the sincere words

that come from the heart.

“I speak sincerely, and my words

and the Lord takes it sincerely—

after all, they are true

and coming from His tiny part and parcel.”

Hridayananda Goswami:

From a BIHS conference on evolution in January 2025:

Scientists, who do not know philosophy, often make metaphysical claims, for making atheistic or theistic pronouncements in the name of science is metaphysical.

These are all metaphysical claims:

If there were a God, he would not use such a violent process as natural selection.

So many species failed. If there is a God, why would He do that?

Scientists discount God because there is no empirical evidence for Him, but because God is metaphysical, you could never prove Him by physical evidence.

If the scientists do not know philosophy they can make philosophical statements thinking they are doing science.

Bhaktivedanta Nemi Maharaja (formerly Jnana Das):

From a BIHS conference on evolution in January 2025:

[Regarding Srila Prabhupada] What thinker in human society has ever thought of his teaching extending for 10,000 years?

Although the scientists speak against consciousness, they are doing it with the consciousness they deny. This contradiction is childish.

Drutakarma Prabhu:

From a BIHS conference on evolution in January 2025:

In archeology there is a jawbone that is reported as belonging to several different hominids.

Nanda Dasi:

From a class on Bhagavad-gita 2.48 in Alachua on February 23, 2025:

The theme of remaining steady in one’s service in either success or failure is described throughout Bhagavad-gita in 2.48, 4.22, 13.8–12, etc.

“May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.” – Nelson Mandela.

It looked that Manigriva and Nalakuvara failed because they were cursed, and because they had to stand as trees for so many years that seemed like another failure. Then after they got Krishna’s darsana in Gokula Vrindavan, they decided to return to their heavenly planet. That seems like a failure that they left the abode of the Lord to go to heaven. But in Gopala Campu, we learn that they took birth in Vrindavan and became bards who narrated Krishna’s pastimes.

Our conception is that failure is bad, but that is not Krishna’s conception.

Edison tried a thousand times to make a light bulb and failed. He was not discouraged, and said, “I didn’t fail. I learned a thousand ways not to make a light bulb.”

If failure makes you determined to try harder, that is a success. And if success makes you proud, then that pride can become a cause of failure.

Krishna makes the point that there is no failure in Bg. 2.40 and related verses.

Our tendency is to see externally, but we have to learn to see internally, how our soul is benefiting from the experience.

Our endeavor, our intention, and our actions, we have to offer to the Lord. The result is up to Krishna.

The Pandavas’ lives were filled with problems, and not just small problems, but big problems. Still Kunti was happy because the problems made her think of Krishna and that was a blessing.

Do not judge an event at that moment. Wait for some time. Get good association. Be patient.

Krishna gives devotees custom karma.

Pariksit was unrighteously cursed, but as a result the Bhagavatam was spoken.

Comments by me:

Krishna advises Arjuna how to act for him: “Therefore, O Arjuna, surrendering all your works unto Me, with full knowledge of Me, without desires for profit, with no claims to proprietorship, and free from lethargy, fight.” (Bhagavad-gita 3.30)

“‘What if people don’t want to hear our message?’ Pradyumna asked.

“‘The people might not understand our message, but Krishna will be pleased,’ Prabhupada replied. ‘And that is our mission. . . . We must not be disappointed that no one is hearing Krishna consciousness. We will say it to the moon and stars and all directions. We will cry in the wilderness, because Krishna is everywhere. We want to get a certificate from Krishna that, “This man has done something for Me.” Not popularity. If a pack of asses says you are good, what is that? We have to please Krishna’s senses with purified senses.’” (Srila Prabhupada-lilamrita, Volume 7 (Srila Prabhupada-lila), Chapter 3)

Comment by Pran Govinda Swami:

Failure is not final. See it like a bump, and keep going.

Comment by someone else:

If Krishna is our best friend, then everything is happening for our benefit. We can cultivate this consciousness.

Yogesvara Prabhu:

From Golden Avatar, his biography on Lord Caitanya presently in production:

“Scholarship may have been in his future, but for his first few years Nimai majored in mischief.”

“He particularly enjoyed stories about naughty child Krishna, which likely inspired him. They were both in the habit of stealing food.”

“Initiation, diksha, was no small matter. It was the formal link between the disciple and a lineage of teachers that extended back to Vishnu at the dawn of the universe, to the moment when beings estranged from God left the eternal realm. The material universe was their playground, a gift from the creator, a theater where they could act out their fantasies, until contact with a qualified teacher set them on course back to their sacred selves.

“Initiation into that distinguished lineage was the most precious of all gifts, and it was cemented with solemn vows. The disciples promised to strictly follow the guru’s instructions, no matter how difficult, and the guru promised to liberate his disciples from future births and restore them to their place in eternity.”

“The qualification of a saragrahi guru such as Ishwara Puri was an ability to breathe life into the words of scripture. The mysteries of bhakti were not mysteries because they were unknown or withheld. They were mysteries because few people understood their meaning as deeply as he did.”

“The singers never felt self-conscious or ashamed, since sankirtan took them to a place beyond appearances and judgment. Excited by Nimai’s example of unrestrained physical expression, dancers shed their inhibitions, grabbed hands and twirled, all smiles and laughter.”

Govinda Kaviraja Prabhu:

From Bhagavatam classes in Tallahassee:

As a child is looking here and there, not knowing what he really wants, the soul in the heart of the body, is desiring something, but he is not sure what will satisfy him.

Murli Gopal Prabhu:

From a BIHS conference on evolution in January 2025:

Although foot size varies continuously, we buy shoes of a discrete size. Similarly, although our desires vary, we take a body of a certain species.

Gaurachand Prabhu:

If you chant one attentive prayerful round of japa before you read, you’ll find it is easier to understand and appreciate what you read.

In a lecture Srila Prabhupada said that 90% of our progress is made by chanting.

Gates to Successful Japa Practice

Fundamentals

sit properly

rise early

pronounce clearly

find a quiet place

Mind and intellectual

mind is best friend and worst enemy

use intelligence to guide the mind by remembering the philosophy

Opening our feelings

holy name is heart deep not lip deep

Vrindavana Dasa Thakura says in Chaitanya-bhagavata that bhakti is crying while chanting the holy name.

Cry for the right reason.

If you cannot, find any genuine emotion for Krishna.

Mercy

Beg for mercy of the Lord and the Vaishnavas.

At least for one round focus on pronunciation.

Just try to add one good habit at a time. Until you master it, do not add another.

If you have no faith, go to Vrindavan, Mayapur, or Puri, and you will see people really attached to Radha-Krishna, and that will increase your faith.

Comments by me, some made verbally:

In Folio Srila Prabhupada quotes the phrase ceto darpana over 700 times, so the understanding that nama-sankirtana cleanses the mind was very important to him.

If we understand that only krishna-prema will completely satisfy the soul, and that we must chant attentively to attain that stage, then we will do whatever is required to chant attentively. Just like we know to go to India, we need a passport, we need money, and we need an airline ticket. Because we really want to go there, somehow or other we will acquire those things.

If you think that if you chant your japa in the morning, that by Krishna’s grace, you will have a more successful day, however you define successful, it is easier to become enthusiastic to do it.

You have to set an alarm to remind yourself to go to sleep.

Ravindra Svarupa Prabhu says that we all want attention, and Krishna is so reciprocal that if we pay attention to Him, He will pay attention to us.

Sacinandana Swami says we should chant japa with the desire to connect with Krishna.

Standing I find better than walking because if you walk you have to pay attention to where you are walking.

I found that when I tried to chant with one-pointed attention, I ended up chanting a lot quicker.

Comment by Govinda Kaviraja: I did not push my son to do japa. The only thing I required is our thirty-minute Bhagavatam class reading and discussion. Later he added japa and other devotional practices because he acquired the intelligence to understand their value from our Bhagavatam discussion.

-----

Krishna says in both Bhagavad-gita 8.22 and 11.54 that he is attained by bhakti (bhaktya) [devotional service] that is unalloyed or undivided (ananyaya). Queen Kunti, the mother of the devotee hero, Arjuna, prays for this with a beautiful simile:

tvayi me ’nanya-visaya

ratim udvahatad addha

gangevaugham udanvati

“O Lord of Madhu, as the Ganges forever flows to the sea without hindrance, let my attraction be constantly drawn unto You without being diverted to anyone else.” (Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.8.42)

Today’s Inspiring ISKCON Achievements and Events! February 28

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff Writer The Barber who Shaved the Lord's Hair! Tomatoes from Heaven. ISKCON Mayapur Kirtan Mela 2025 Day - 4. Garbage In Garbage Out. Srila Jagannatha Dasa Babaji - Disappearance. Saved from the Clutches of Maya. Sri Rasikananda Deva Goswami. GBC Releases Highlights Report for Final Day of Annual General Meeting. H. H. Tamal Krishna Goswami Maharaja's Disappearance Day. Program Sri Navadvipa-dhama Virtual Parikrama: A Sacred Journey Anytime, Anywhere. Holi Katha with Krishna Murari Goswami. Mayapur Kirtan Mela 2025 Day 3 (photos). Srimad-Bhagavatam Class by H. H Candramauli Swami - Mayapur. TOVP SCIENCE MUSEUM TEAM IN MAYAPUR: ADVANCING A HISTORIC VISION Continue reading "Today’s Inspiring ISKCON Achievements and Events! February 28

→ Dandavats"

Srila Jagannatha Dasa Babaji’s and Sripada Tamal Krishna Goswami’s Disappearance Day

Giriraj Swami

Today is the disappearance day of Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja.

Today is the disappearance day of Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja.

gauravirbhava-bhumes tvam nirdesta saj-jana-priyah

vaisnava-sarvabhaumah sri-jagannathaya te namah

“I offer my respectful obeisances unto Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja, who is respected by the entire Vaishnava community and who indicated the place where Lord Chaitanya appeared.”

Today is also the disappearance day of Sripada Tamal Krishna Goswami, my sannyasa-guru, siksa-guru, and dear friend, and you can read about both Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji and Tamal Krishna Goswami below:

Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja comes in the Gaudiya Vaishnava disciplic succession after Srila Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura and Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana. He was a renounced ascetic, fully engaged in chanting the holy names of Krishna and meditating on the pastimes of Krishna. For some time, he made his residence at Surya-kunda in Vraja-dhama, near the temple of Suryadeva, where Srimati Radharani used to come and worship the sun-god—or, I should say, where She used to come to meet Krishna on the pretext of coming to worship the sun-god.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura, who comes in the disciplic succession after Jagannatha dasa Babaji, accepted Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja as his main guru, his siksa-guru. Once, some of Jagannatha dasa Babaji’s disciples in Vraja approached the Thakura and complained that although they had come to Vraja to live like Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja, fully absorbed in chanting the holy names and meditating on Sri Sri Radha-Krishna’s astakaliya-lila, Babaji Maharaja had refused to instruct them in such topics and had instead engaged them in cultivating tulasi plants, flowers, and vegetables to offer to the Lord. And they requested Bhaktivinoda Thakura to appeal to their guru maharaja to instruct them in the esoteric practices of Krishna consciousness.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura told the disciples, “Actually, your Gurudeva’s instructions are right for you. Because you still have anarthas, for you to sit and try to do nirjana-bhajana [solitary worship] and practice astakaliya-lila-smarana [meditation on the Lord’s eightfold daily pastimes] would be artificial, and you would just become degraded. So you should follow his instructions with full faith and work hard in Krishna’s service. Then, in time, you may be able to chant the holy names purely.”

Eventually, Jagannatha dasa Babaji Maharaja moved to Mayapur, where he lived by the banks of the Ganges, fully absorbed in chanting the holy names. He had the greatest reverence for the holy land of Navadvipa. Although he was so renounced and so absorbed in Krishna consciousness, as his reputation spread, gentlemen would come to him and give him donations. Once, Babaji Maharaja asked one of his servants to take the donations he had received, which he kept in an old burlap bag, and purchase a large pot of rasagullas. All the devotees were surprised, because Jagannatha dasa Babaji was so renounced and lived so simply; he would eat only the simplest rice and dal. Anyway, the servant brought the sweets, and Jagannatha dasa Babaji offered them to his Deities and then distributed them to the cows and dogs in the dhama. He said that the creatures of the dhama were elevated souls and worthy of service.

Later, Babaji Maharaja would not honor prasada until he had shared it with ten newborn puppies. He would wait until they came, and because in his old age his eyelids drooped over his eyes and prevented him from seeing, he would count them with his hands. And only after they had begun to eat would he also partake. He would say, “They are puppies of the dhama. They are not ordinary living entities.” He had so much faith in and affection for the dhama.

He had less affection for Mayavadi impersonalists. He used to say, “Let the dogs come in for darshan, but the impersonalists—kick them out!”

Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji lived to a very old age. Some Vaishnavas say he was just waiting for Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura to come—someone to whom he could impart his special knowledge and realization, for the benefit of humanity. Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura requested to be transferred from his post in Orissa to Bengal so he could be near Navadvipa-dhama. And eventually he was posted at Krishnanagar, near Navadvipa.

Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura did extensive research to determine the actual birthplace of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. He studied old maps, consulted the local people, and visited the different places. Eventually he found a mound where many tulasi trees were growing. He got the intuition that this was the actual birthplace of Lord Chaitanya, but he wanted his intuition to be confirmed. At the time, Jagannatha dasa Babaji was the most renowned Vaishnava, and he was Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura’s siksa-guru. So, Jagannatha dasa Babaji’s disciples brought him to the place with the mound and tulasi plants. He was so old—over a hundred and forty years old, some say—that his disciples had to carry him in a basket. The disciples brought him, but when they came to the site, they didn’t tell him that Bhaktivinoda Thakura had determined it was the birthplace. Still, when Babaji Maharaja arrived there, he spontaneously jumped out of his basket and began to dance in ecstasy, singing the holy names. Thus he confirmed the location of Mahaprabhu’s birthplace.

Srila Jagannatha dasa Babaji’s bhajana-kutira and samadhi are there in Navadvipa-dhama, in Koladvipa. Devotees who perform Navadvipa-parikrama visit there and get his mercy. We also pray to him for his mercy, that we may be instrumental in fulfilling the desires of Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura, Srila Gaurakisora dasa Babaji Maharaja, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, and the other acharyas in the line of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu coming to us through Srila Prabhupada and his disciples.

Today especially, we think of His Holiness Tamal Krishna Goswami Maharaja, who left this world on Jagannatha dasa Babaji’s disappearance day, also in Gauda-mandala-bhumi. Two years ago I was in Dallas for the disappearance day of Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura, just a few months after Goswami Maharaja passed away. As we were observing the ceremony in the temple, I was thinking how Goswami Maharaja was the perfect servant and therefore the fit representative of Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura. Then I thought of him in relation to all of the acharyas in the last two centuries—Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakura, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, and Srila Prabhupada (who are the most prominent of them)—and how he really took their mission to heart. He was absorbed in fulfilling all aspects of their mission: developing Mayapur, distributing books, spreading the chanting of the holy names throughout the world in various ways—all the programs that were so important to our predecessor acharyas.

Although I could speak of Goswami Maharaja’s surrender and service for days, today we have the rare opportunity to hear from His Grace Amoghalila dasa Adhikari. Amoghalila, could you please tell us something about your experiences with him and your realizations about him?

Amoghalila Prabhu:

I am thinking of one or two incidents I can mention, and some realizations I had from them. One was actually the last morning Srila Prabhupada was in Bombay, in Juhu. I was fortunate, actually by Giriraj Maharaja’s mercy, to be able to be in Srila Prabhupada’s room then. After about a month in Bombay, Srila Prabhupada was leaving that morning for Vrindavan. Madhava Prabhu and Upendra Prabhu were also there, though Upendra was in and out of the room.

Srila Prabhupada was just lying on his bed. He could hardly move. He couldn’t even sit up by himself. He was so weak he could barely speak. But then he said something. It was hard to hear what he said, so I leaned closer and asked, “What, Srila Prabhupada?” He said, “Call Tamal.” So, Upendra Prabhu went out to get Tamal Krishna Maharaja. When Goswami Maharaja came into the room, he offered dandavat-pranama (prostrated obeisances) and then got up. Srila Prabhupada asked him about the arrangements for going to Vrindavan. Goswami Maharaja said, “Yes, Srila Prabhupada,” offered dandavat-pranama, and went out. A minute or two later, he came back in. He offered dandavat-pranama, got up, and then told Srila Prabhupada the answer to Prabhupada’s question. He said something, he got something ready, and then he offered dandavat-pranama and went out. This happened at least three times: He came in and went out, he came in and went out, and he came in and went out, all within just a few minutes—it couldn’t have been more than five minutes. Practically every minute he was coming in, offering dandavat-pranama, getting up, talking to Prabhupada for a few seconds or half a minute, offering dandavat-pranama again, and going out.

Later, after Srila Prabhupada left us, when I was Goswami Maharaja’s personal secretary, I mentioned this to him, and he said, “Yes, Srila Prabhupada instructed me to do this. Srila Prabhupada said that because familiarity breeds contempt, it is very important when somebody is intimately serving the spiritual master that they keep a reverential mood.” Goswami Maharaja, of course, was such an intimate servant of Srila Prabhupada’s, yet he always maintained that deep reverence—of course love, also, but at the same time he always had such deep reverence for Srila Prabhupada. Tamal Krishna Maharaja is such an ideal example of a personal servant and disciple.

I am thinking of one other incident then, when I was Goswami Maharaja’s personal secretary in 1978 in Bombay. As I mentioned to Giriraj Maharaja, I think the real reason Goswami Maharaja wanted me to be his personal secretary was so he could train me, because he had seen how disturbing my mismanagement was. I had been the vice president and the so-called manager of Hare Krishna Land, and at one point during that time, Giriraj Maharaja had mentioned to Tamal Krishna Maharaja, “Amoghalila is mismanaging the affairs here.” Goswami Maharaja had said, “There is no mismanagement . . . There is no management!” So, he felt that I needed some training in management. Therefore, he made me his personal secretary, to train me. I think that was the main reason, and he tried to train me and he did.

He did train me a lot, though I didn’t follow his training so well, but one incident when he trained me was very moving. Every time I think about it, I just . . . He was teaching me how to clean the floor. I mean, I had been a devotee for six or seven years, so I had been cleaning floors for a long time. Anyway, once, when I was cleaning the floor, he said, “No, that’s not how you clean the floor,” because I had the cloth bunched up or something. So, he took the cloth from me, got down on his hands and knees, spread the cloth out big, folded it over once, and started cleaning the floor. I tried to stop him; I said, “Maharaja, it’s okay, it’s okay. I’ll do it.” He responded, “No, I want to show you how to do it.” And he cleaned for quite a while. He cleaned a large area, and I was protesting, but he said, “No. Just watch what I am doing.” He had the cloth spread out quite big, and he cleaned for some time. I tried to stop him again, but he explained, “No, Srila Prabhupada did this to me. Srila Prabhupada showed me like this. He got down on his hands and knees and he cleaned the floor to show me how to do it. So why can’t you let me show you how to do it?”

So, Tamal Krishna Goswami was the perfect servant of Srila Prabhupada. And as you said, Maharaja, the perfect servant or ideal servant becomes the ideal representative. Goswami Maharaja was so strict in following Srila Prabhupada exactly, to the detail, even how you open up a cloth and fold it and clean the floor—every detail, everything! These are just a couple of little incidents I was thinking about.

Hare Krishna.

Giriraj Swami: When you began, saying how Tamal Krishna Goswami would come and offer full obeisances, I thought of what some devotees told me about his routine in Dallas after Srila Prabhupada left. Every night, he would go into Srila Prabhupada’s room, where the deity of Srila Prabhupada was installed, and chant his last Gayatri and put Srila Prabhupada to rest. He wanted to do that as his personal service. And they told me that whenever Goswami Maharaja would leave the temple premises, even for an hour or two, he would first circumambulate the building. They gave me the impression that he was circumambulating Srila Prabhupada, although, of course, he was circumambulating the other deities as well. But he was very conscious of Srila Prabhupada. In general, he was always very conscious of his lords and masters.

I also think of how, after Srila Prabhupada left, Goswami Maharaja distributed different remnants of Srila Prabhupada to different devotees. He had one of Srila Prabhupada’s teeth, which he had placed in a silver capsule and hung around his neck. Indradyumna Swami, who is quite expert in getting deities and sacred relics, once was asking Tamal Krishna Goswami about the tooth—what was eventually going to happen to it. And Tamal Krishna Goswami understood that Indradyumna Maharaja was trying to see if he could one day get the tooth. Goswami Maharaja just laughed and said, “Don’t even think of it. I am taking it with me. Even after I leave, it will stay with my body.” His idea was that by the tooth being put into his samadhi, people who circumambulated his samadhi or offered obeisances there would get the benefit of circumambulating Srila Prabhupada’s tooth, of offering obeisances to his tooth. And on the absolute platform, Srila Prabhupada’s tooth is as worshippable as he is.

Devotee: The tooth was kept with him, even when he was put into samadhi?

Giriraj Swami: Yes, it was always kept with him.

Hare Krishna!

[A talk by Giriraj Swami on Jagannatha dasa Babaji’s disappearance day, February 20, 2004, Carpinteria, California]

TOVP Presents: Once In A Lifetime – A Global Gathering for Lord Nrsimha’s Appearance in the TOVP

- TOVP.org

On February 2, 2024 Lord Nrsimha appeared in the TOVP, as devotees from around the world gathered for the opening of His astounding and beautiful temple wing. A moment of profound significance.

This video documents that extraordinary day, one that Vaishnavas worldwide had been waiting for. Feel the energy, the devotion, and the sheer joy as the celebrations unfold at the Temple of the Vedic Planetarium. This is a glimpse into the heart of unwavering faith.

Video credit: Ramasundara das

TOVP NEWS AND UPDATES – STAY IN TOUCH

Visit: www.tovp.org

Support: https://tovp.org/donate/seva-opportunities

Email: tovpinfo@gmail.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/tovp.mayapur

YouTube: www.youtube.com/user/tovpinfo

Twitter: https://twitter.com/TOVP2022

Telegram: https://t.me/TOVP_GRAM

WhatsApp: https://s.tovp.org/whatsappcommunity1

Instagram: https://s.tovp.org/tovpinstagram

App: https://s.tovp.org/app

News & Texts: https://s.tovp.org/newstexts

Store: https://tovp.org/tovp-gift-store/

Spreading Krishna Consciousness Globally with Devotion! February 27

→ Dandavats

By Dandavats Staff Writer

By Dandavats Staff WriterHH BB Bhagavat Swami: Shivaratri. Mayapur Kirtan Mela 2025 Day - 3. Srila Prabhupada pastimes. Mayapur Kirtan Mela 2025 Day 2 (photos). Prabhupada Legacy Museum Tour with His Grace Gauranga Prabhu. The Mind Steals Our Identity. Srimad-Bhagavatam Class by HG Prahlad Prabhu. HG Vaisesika Prabhu's MOST Inspiring Sankirtan Moments. Maha Shivaratri Celebrations - Rishikesh Kirtan Fest 2025 - Indradyumna Swami. Live Yuga Dharma Harinam Sankirtan in NYC. The Extraordinary Mercy of Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu. The Birthplace of a Spiritual Pioneer: ISKCON's Project to Glorify Srila Bhaktivinoda Thakur. ISKCON Jyotisar. Uttar Pradesh Padayatra. Srimad-Bhagavatam Class by HG Malati Devi Dasi Continue reading "Spreading Krishna Consciousness Globally with Devotion! February 27

→ Dandavats"

Shiva-ratri

Giriraj Swami

Today is Shiva-ratri. Vaishnavas generally do not celebrate Shiva-ratri, and to begin, I will explain why, with reference to the Bhagavad-gita. We read from Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Chapter 7: “Knowledge of the Absolute”:

Today is Shiva-ratri. Vaishnavas generally do not celebrate Shiva-ratri, and to begin, I will explain why, with reference to the Bhagavad-gita. We read from Bhagavad-gita As It Is, Chapter 7: “Knowledge of the Absolute”:

TEXT 23

antavat tu phalam tesam

tad bhavaty alpa-medhasam

devan deva-yajo yanti

mad-bhakta yanti mam api

TRANSLATION

Men of small intelligence worship the demigods, and their fruits are limited and temporary. Those who worship the demigods go to the planets of the demigods, but My devotees ultimately reach My supreme planet.

PURPORT by Srila Prabhupada

Some commentators on the Bhagavad-gita say that one who worships a demigod can reach the Supreme Lord, but here it is clearly stated that the worshipers of demigods go to the different planetary systems where various demigods are situated, just as a worshiper of the sun achieves the sun or a worshiper of the demigod of the moon achieves the moon. Similarly, if anyone wants to worship a demigod like Indra, he can attain that particular god’s planet. It is not that everyone, regardless of whatever demigod is worshiped, will reach the Supreme Personality of Godhead. That is denied here, for it is clearly stated that the worshipers of demigods go to different planets in the material world but the devotee of the Supreme Lord goes directly to the supreme planet of the Personality of Godhead.

COMMENT by Giriraj Swami

This is logical. As Srila Prabhupada remarked, if you buy a ticket to Calcutta, you cannot expect to reach Bombay. If you worship a demigod, you go to the planet of the demigod. If you worship Krishna, you reach the supreme abode of Krishna.

PURPORT (continued)

Here the point may be raised that if the demigods are different parts of the body of the Supreme Lord, then the same end should be achieved by worshiping them. However, worshipers of the demigods are less intelligent because they don’t know to what part of the body food must be supplied. Some of them are so foolish that they claim that there are many parts and many ways to supply food. This isn’t very sanguine. Can anyone supply food to the body through the ears or eyes? They do not know that these demigods are different parts of the universal body of the Supreme Lord, and in their ignorance they believe that each and every demigod is a separate God and a competitor of the Supreme Lord.

COMMENT by Giriraj Swami

There is a verse in the Fourth Canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam that says that just as by pouring water on the root of a tree all the limbs and branches and leaves are watered and that just as by supplying food to the stomach all the different limbs of the body are nourished, similarly, by offering worship or rendering service to the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Krishna, all of the demigods and all living entities are served and satisfied.

yatha taror mula-nisecanena

trpyanti tat-skandha-bhujopasakhah

pranopaharac ca yathendriyanam

tathaiva sarvarhanam acyutejya

“By giving water to the root of a tree one satisfies its branches, twigs, and leaves, and by supplying food to the stomach one satisfies all the senses of the body. Similarly, by engaging in the transcendental service of the Supreme Lord one automatically satisfies all the demigods and all other living entities.” (SB 4.31.14)

PURPORT (concluded)

The results achieved by the demigods’ benedictions are perishable because within this material world the planets, the demigods, and their worshipers are all perishable. Therefore it is clearly stated in this verse that all results achieved by worshiping demigods are perishable, and therefore such worship is performed by the less intelligent living entity. Because the pure devotee engaged in Krsna consciousness in devotional service of the Supreme Lord achieves eternal blissful existence that is full of knowledge, his achievements and those of the common worshiper of the demigods are different. The Supreme Lord is unlimited; His favor is unlimited; His mercy is unlimited. Therefore the mercy of the Supreme Lord upon His pure devotees is unlimited.

COMMENT

Everything material is temporary. The demigods themselves—the bodies of the demigods—are temporary. The bodies of their worshippers are temporary. The planets of the demigods are temporary, and the fruits that one obtains from worshipping them are temporary. The demigods have authority only within the material world. They can give only material benefits to their worshippers. It is only Vishnu, or Krishna, who can award liberation from material bondage. No demigod can grant liberation. And beyond liberation, the devotees of Krishna also achieve krsna-bhakti, or krsna-prema—the ultimate goal of life.

Srila Prabhupada said that the impersonalists want to become one with God but that the devotees actually become greater than God, because God comes under their control. We see in the Bhagavad-gita that Krishna is acting as the chariot driver of Arjuna. Arjuna is commanding Krishna, senayor ubhayor madhye ratham sthapaya me ’cyuta: “Please draw my chariot between the two armies so I can see who has assembled on the battlefield to fight.” The Lord likes to be controlled by His devotees, and He comes under the control of their pure love. Of course, the Lord is supreme—no one is equal to Him or greater than Him (na tat-samas cabhyadikas ca drsyate)—but out of love He becomes subordinate to His devotee. The idea of becoming one with the Lord is repugnant to a devotee, because in that impersonal oneness there is no service, no exchange of love.

The demigod worshippers, as described in this verse, are alpa-medhasah, “less intelligent.” The opposite of alpa-medhasah is su-medhasah, or “very intelligent.” Those who worship Krishna, especially through the sankirtana movement in the present age, are described as su-medhasah.

krsna-varnam tvisakrsnam

sangopangastra-parsadam

yajnaih sankirtana-prayair

yajanti hi su-medhasah

“In the age of Kali, intelligent persons perform congregational chanting to worship the incarnation of Godhead who constantly sings the names of Krsna.” (SB 11.5.32, Cc Adi 3.52)

Further, the demigods are not able to give even material benedictions without the sanction of the Supreme Lord. Isvarah sarva-bhutanam hrd-dese ’rjuna tisthati— the Lord is in the heart of everyone, including the demigods, so unless He gives His sanction, the demigods themselves cannot give even limited temporary benefits. So, from every point of view, one should worship Krishna. And devotees of Krishna need not worship any demigod. Krishna, the Supreme Lord, is like the king, and the various demigods are like ministers in the cabinet of the king or department heads in the government. As Srila Prabhupada said, if you pay taxes to the central treasury, you need not bribe the ministers or officers in charge of different departments. When you pay your taxes into the central treasury, you have met your obligation and are entitled to all the benefits of a citizen.

In fact, worship of demigods is discouraged in the Bhagavad-gita. The Supreme Lord Krishna says,

ye ’py anya-devata-bhakta

yajante sraddhayanvitah

te ’pi mam eva kaunteya

yajanty avidhi-purvakam

“Those who are devotees of other gods and who worship them with faith actually worship only Me, O son of Kunti, but they do so in a wrong way.” (Gita 9.23)

Therefore, Vaishnavas do not celebrate Shiva-ratri.

Yet there is another, confidential aspect to Lord Shiva that ordinary people with insufficient knowledge of shastra, of Srimad-Bhagavatam, do not know: Lord Shiva himself is the greatest Vaishnava (vaisnavanam yatha sambhuh), and the worship of Vaishnavas, the service of Vaishnavas, and the glorification of Vaishnavas is included in Krishna consciousness. In fact, it is most highly recommended. So, in an assembly of learned devotees we can appreciate Shiva as a Vaishnava. But otherwise, we don’t worship Lord Shiva, because if we did, people could misunderstand and conclude, “ISKCON devotees worship Shiva, so we will too.” And they will worship Lord Shiva for material benefit. Or they may think that Lord Shiva is on the same level as Krishna—or supreme.

In India there is a history of debate between Vaishnavas and Shaivites over who is supreme. And as Srila Prabhupada said, in such debates the Vaishnavas always win. Still, that sense of competition is there. Shaivites say, “Shiva is supreme,” and Vaishnavas respond, “No, Vishnu is supreme.”

The Illustrated Weekly of India once carried an article by Agehananda Bharati, an Austrian-born Indologist and Advaitan sannyasi, under the title “Hare Krishna vs Shiva Shiva.” In the article, Bharati gave his version of a series of exchanges and debates he had had with “Swami Hridayananda” of ISKCON. I shared my impression with Srila Prabhupada that the Weekly’s editor, Khushwant Singh, had run the piece, along with that title, to make us all—believers in general—look silly, bickering over deities and evidence. Prabhupada agreed with my assessment. “Yes,” Prabhupada said. “Bharati is a fool, but Singh is a demon.”

Srila Prabhupada wanted us to respond to articles. Once, later, a devotee informed him of a newspaper report that the Balaji temple at Tirupati, which has immense wealth from donations to the Deity, was going to loan money to encourage local industries. Srila Prabhupada became concerned and said that we should write a letter to the editor stating that the money belonged to Balaji and should have been used for Balaji’s purpose. And what is Balaji’s purpose? Srila Prabhupada quoted, paritranaya sadhunam vinasaya ca duskrtam/ dharma-samsthapanarthaya sambhavami yuge yuge. Balaji comes to establish the principles of religion. Balaji’s money should be used for Balaji’s purpose—to establish the principles of religion. And what is the principle of religion for the present age? The yuga-dharma in Kali-yuga is hari-nama-sankirtana. The money should be used to promote hari-nama-sankirtana.

When I visited Madras in 1971, I met many intellectuals whose attitude was similar to the editor’s. They thought, “Oh, how silly. You are arguing that Krishna is supreme, and someone else is arguing that Shiva is supreme.” These impersonalists considered themselves to be more intelligent than the naive sentimentalists who worship particular deities, and they counted us as naive sentimentalists because we love Krishna, worship Krishna, chant Krishna’s name, and preach Krishna’s supremacy. There are many Shaivites in Madras, and they argue that Shiva is supreme.

As the first ISKCON devotee to visit Madras, I became quite a sensation—an American Vaishnava. Most people there had never seen a Western sadhu, and they wanted to help. Several suggested that I meet a Mr. Ramakrishna, who they said was pious and religious and would be happy to hear of our activities. So, I met him, and he turned out to be one of those people who thought that Shiva was supreme. Very quickly we came to blows—verbal blows. He had a volatile nature, and he became angry. He became red in the face and raised his voice, and the meeting ended abruptly. But I kept preaching and meeting people who suggested, “You have to meet Mr. Ramakrishna. He is a very pious man. He is a very religious man.” And I imagine that he was meeting people, saying, “Oh, you should meet the Hare Krishna devotees. They are very good people. They are doing excellent work.”

After a few weeks, I thought, “Maybe I should give it another try. This time I will be more careful.” So, I phoned him, and he immediately agreed to meet me. That made me think that people were also speaking favorably about us to him and that it was embarrassing for him that we had disagreed so vehemently. We met, and I tried to restrain myself, and he tried to restrain himself, but eventually we came to the same point: Who is supreme—Krishna (Vishnu) or Shiva? The argument escalated, but neither of us wanted it to end the same way as the last one had. Then I got an inspiration and suggested, “In two weeks my spiritual master, His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, is coming to Madras. So instead of us discussing, why don’t I invite you to meet him when he comes, and you can discuss with him directly.” He liked the idea. It was a way out for both of us. And ultimately, what could be better than to meet a pure devotee of Krishna?

After Srila Prabhupada arrived, Mr. Ramakrishna came to meet him. “I met your disciple Giriraj,” Mr. Ramakrishna said, “and I argued that Shiva is supreme, and he argued that Krishna is supreme. So, who is supreme?” Srila Prabhupada took a completely different approach. He didn’t enter into the argument about who was supreme. Rather, he said, “There are two words in Sanskrit—puja and bhakti. In puja one worships the deity to get some material benefit, and in bhakti one worships only to give pleasure to the deity, without expectation of personal return.” Then Srila Prabhupada said, “Generally the worshippers of Shiva engage in puja—they worship to get some material benefit—whereas in bhakti we worship Krishna for the sake of Krishna’s pleasure, just to please Him.”

“Is it not possible,” Mr. Ramakrishna asked, “to worship Shiva in the mood of bhakti?” And Srila Prabhupada replied, “It is possible, but it would be exceptional. For example, generally people go to a liquor shop to buy liquor. Now, one could go for another purpose, but that would be an exception. Generally people go to buy liquor.” Mr. Ramakrishna was satisfied with the answer. Srila Prabhupada did not enter into the controversy over which deity was supreme; rather, he explained different moods in the worship of different deities.

Later, toward the end of Srila Prabhupada’s stay in Madras, a wealthy householder invited Prabhupada to his home for the consecration of his temple. The host had invited many dignitaries, and although the temple was a good size for a home, it wasn’t large enough to accommodate Srila Prabhupada’s disciples along with all the dignitaries. So Srila Prabhupada and the others went inside the temple, and we disciples looked in from outside. As part of the ceremony, the host distributed flower petals to the guests to offer to the deity of Lord Shiva, a Shiva-linga. And we all were interested to see how Srila Prabhupada would deal with the situation. At the appropriate moment, all the participants threw their flower petals on the deity of Lord Shiva—except for Srila Prabhupada. He threw his in the corner. We thought, “He is the acharya. We have to learn from him.” So, after the ceremony, when the other invitees came out, we went into the temple and looked in the corner. And there we saw a small Deity of Krishna. Prabhupada had offered his flowers to Krishna.

As Srila Prabhupada’s representatives, ISKCON and its members are meant to follow Srila Prabhupada’s instructions and precedents. And we must be careful not to encourage people’s misconceptions—even if what we do is otherwise all right. If we were to observe Shiva-ratri with participants who are not well versed in shastric conclusions, in Vaishnava siddhanta—if we were to celebrate Shiva-ratri to cater to Hindus who want to worship Lord Shiva on Shiva-ratri but who do not know his actual position as a Vaishnava—they might mistakenly conclude that we accept Lord Shiva on the same level as Krishna. Then, even if they chant the holy name of Krishna, as long as they maintain the idea that Shiva and Krishna are the same, they will not make much advancement, because they will be committing an offense against the holy name (nama-aparadha). The second of the ten offenses against the holy name is to consider the names of demigods such as Lord Shiva to be equal to or independent of the name of Lord Vishnu.

That is why we don’t observe Shiva-ratri. And as Vaishnavas, we have no need to worship Shiva, because we are worshipping Krishna directly. Still, we may worship Lord Shiva as a Vaishnava, a devotee of Krishna, because the worship of Krishna’s devotees pleases Lord Krishna.

The basic definition of bhakti is given by Srila Rupa Gosvami in Sri Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu (1.1.11):

anyabhilasita-sunyam

jnana-karmady-anavrtam

anukulyena krsnanu-

silanam bhaktir uttama

“One should render transcendental loving service to the Supreme Lord Krsna favorably and without desire for material profit or gain through fruitive activities or philosophical speculation. That is called pure devotional service.” In pure devotional service, one should have no desire other than to serve and please Krishna (anyabhilasita-sunyam). And jnana-karmady-anavrtam—one’s service should not be covered by jnana, speculative knowledge that leads to a conclusion of impersonal monism, or by karma, fruitive work, as in ordinary puja, which one performs for personal gain. In ordinary affairs, for example, one may invite someone to a restaurant and give him food and drink in the hope of getting some benefit from him. In a similar way, one may offer bael leaves and ganga-jala to Lord Shiva in order to get some personal return. That fruitive mentality has no place in pure devotion, and certainly the speculative idea of merging and becoming one with God has no place. Anything that covers the true nature of bhakti has no place (jnana-karmady-anavrtam). Pure devotional service must be rendered favorably to Krishna (anukulyena krsnanusilanam).

Acharyas who have commented on this verse from the Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu, such as Srila Jiva Gosvami, Srila Visvanatha Chakravarti Thakura, and Srila Prabhupada, have explained that “Krishna” does not mean Krishna alone. Srila Prabhupada’s Introduction to The Nectar of Devotion discusses this verse in detail and includes much of the commentaries of Jiva and Visvanatha. And all agree that in this verse “Krishna” does not mean Krishna alone but includes His personal expansions, such as Lord Ramachandra, Lord Nrsimha, Lord Varaha, and other visnu-tattvas, as well as His name, form, qualities, pastimes, paraphernalia, and pure devotees. “Krsna includes all such expansions, as well as His pure devotees,” Srila Prabhupada writes. Serving and worshipping pure devotees is included within uttama-bhakti, pure devotional service to Krishna, and thus devotees of Krishna sometimes worship Lord Shiva as a pure devotee.

Many of Lord Shiva’s pastimes are described in Srimad-Bhagavatam. Srimad- Bhagavatam is the perfectly pure, spotless Purana (srimad-bhagavatam puranam amalam) and is called the Paramahamsa-samhita because it is meant for the highest class of transcendentalists, who are completely free from envy. It is the topmost scripture and discusses no subject other than Krishna and pure devotional service. These pastimes with Lord Shiva show his true nature, or internal mood, as a Vaishnava, a pure devotee of Krishna. In one pastime the hundred sons of King Barhisat, known as the Pracetas, were engaged in austerities to realize Vishnu, or Krishna. Lord Shiva met them and, appreciating their austerities, acted as their guru to guide them. He gave them a series of prayers to sing to please Lord Vishnu and become pure devotees. Upon first meeting the Pracetas, he made the following statement, which I shall read from Srimad-Bhagavatam, Canto Four, Chapter Twenty-four: “Chanting the Song Sung by Lord Siva”:

TEXT 30

atha bhagavata yuyam

priyah stha bhagavan yatha

na mad bhagavatanam ca

preyan anyo’sti karhicit

TRANSLATION

You are all devotees of the Lord, and as such I appreciate that you are as respectable as the Supreme Personality of Godhead Himself. I know in this way that the devotees also respect me and that I am dear to them. Thus no one can be as dear to the devotees as I am.

PURPORT by Srila Prabhupada

It is said, vaisnavanam yatha sambhuh: Lord Siva is the best of all devotees. Therefore all devotees of Lord Krsna are also devotees of Lord Siva. In Vrndavana there is Lord Siva’s temple called Gopisvara. The gopis used to worship not only Lord Siva but Katyayani, or Durga, as well, but their aim was to attain the favor of Lord Krsna. A devotee of Lord Krsna does not disrespect Lord Siva but worships Lord Siva as the most exalted devotee of Lord Krsna. Consequently, whenever a devotee worships Lord Siva, he prays to Lord Siva to achieve the favor of Krsna, and he does not request material profit. In Bhagavad-gita (7.20) it is said that generally people worship demigods for some material profit. Kamais tais tair hrta jnanah. Driven by material lust, they worship demigods, but a devotee never does so, for he is never driven by material lust. That is the difference between a devotee’s respect for Lord Siva and an asura’s respect for him. The asura worships Lord Siva, takes some benediction from him, misuses the benediction, and ultimately is killed by the Supreme Personality of Godhead, who awards him liberation.

Because Lord Siva is a great devotee of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, he loves all the devotees of the Supreme Lord.

COMMENT

This is a symptom of a devotee. One who is actually a devotee of the Supreme Lord will love all other devotees of the Supreme Lord. Lord Shiva truly loved the Pracetas. He went out of his way to help them, and further, he respected them as representatives of the Supreme Lord.

PURPORT (continued)

Lord Siva told the Pracetas that because they were devotees of the Lord, he loved them very much. Lord Siva was not kind and merciful only to the Pracetas; anyone who is a devotee of the Supreme Personality of Godhead is very dear to Lord Siva. Not only are the devotees dear to Lord Siva, but he respects them as much as he respects the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Similarly, devotees of the Supreme Lord also worship Lord Siva as the most dear devotee of Lord Krsna. They do not worship him as a separate Personality of Godhead. It is stated in the list of namaparadhas that it is an offense to think that the chanting of the name of Hari and the chanting of Hara, or Siva, are the same. The devotees must always know that Lord Visnu is the Supreme Personality of Godhead and that Lord Siva is His devotee. A devotee should be offered respect on the level of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, and sometimes even more respect. Indeed, Lord Rama, the Personality of Godhead Himself, sometimes worshiped Lord Siva. If a devotee is worshiped by the Lord, why should a devotee not be worshiped by other devotees on the same level with the Lord?

COMMENT

In other words, if a devotee is worshipable by the Lord Himself, why should other devotees not worship a devotee on the same level as the Lord? Saksad-dharitvena samasta-sastrair: the spiritual master is worshipped on the same level as the Supreme Lord. But kintu prabhor yah priya eva tasya—although one honors the spiritual master as much as the Lord, one knows that he is not identical with the Lord but is a most confidential servitor of the Lord.

PURPORT (continued)

If a devotee is worshiped by the Lord, why should a devotee not be worshiped by other devotees on the same level with the Lord? This is the conclusion. From this verse it appears that Lord Siva blesses the asuras simply for the sake of formality.

COMMENT

In relation to the demons (asuras), Lord Shiva thinks, “Okay, they are worshipping me. They want something. Okay, I will give them something.” Thus, one of Shiva’s names is Asutosa, because he gives benedictions very easily. As Srila Prabhupada said, “Many demons go to bother Lord Shiva: ‘Give me this. Give me that.’ And his name is Asutosa. He gives immediately: ‘All right, take it. Go away. Don’t bother me.’ ” He blesses them simply for the sake of formality, to get rid of them.

PURPORT (concluded)

From this verse it appears that Lord Siva blesses the asuras simply for the sake of formality. Actually he loves one who is devoted to the Supreme Personality of Godhead.

COMMENT

In addition to the pastimes of Lord Shiva described in Srimad-Bhagavatam, there are many pastimes with Lord Shiva in Vrindavan that show his great love for Lord Krishna and his eagerness to serve Him. And Lord Krishna’s great-grandson, Vajranabha, who established many of the main temples in Vrindavan, installed several deities of Lord Shiva in Vraja to honor his pastimes there.

One prominent deity of Lord Shiva in Vraja is Nandesvara Mahadeva, at Nanda-grama. He is worshipped in a small temple situated within the courtyard of the main temple there, and every day, the pujaris offer him the remnants of food that has been offered to Lord Krishna in the main temple. This tradition goes back to the time when Krishna and Balarama lived in Nanda-grama with Nanda Maharaja and Mother Yasoda. As the local history goes, when Lord Shiva came to Nanda Bhavan to see his beloved Lord Krishna, he arrived in his usual attire—with matted hair, ashes all over his body, and a snake wrapped around his neck—playing his damaru drum. When Mother Yasoda came to the door, she could not bring herself to let this wild-looking ascetic in to see her darling little child. And so she gave him alms and sent him on his way. As he was leaving, however, baby Krishna began to cry. Mother Yasoda tried in many ways to pacify Him, but she couldn’t; He was inconsolable. She began to think that she might have committed an offense against the ascetic and that he had put a spell on her baby, so she sent for him. In the end, Lord Shiva was found in the forest now known as Asesvara-vana, the forest of hope, where he was praying, hoping against hope (asa means “hope”), that he would somehow get the darshan of Nandalal, Krishna. Lord Shiva was very happy when he was asked to return to Nanda Bhavan, and as soon as he arrived, baby Krishna stopped crying. But when Mother Yasoda indicated that it was time for him to leave, Krishna again began to cry. He didn’t want Lord Shiva to leave. It was then settled that Lord Shiva would remain permanently in Nanda Bhavan and get the caranamrta and food remnants of Nandalal every day. And to this day it has been so.

Another important deity is Kamesvara Mahadeva, who resides at Kamyavana. He fulfills all desires, and so devotees pray to him to give them pure devotional service to Krishna.

Chaklesvara Mahadeva resides at Chakra-tirtha, by Manasi-ganga at Govardhana Hill. It is said that Sanatana Gosvami was good friends with Lord Shiva and always resided near him in Vraja. At Manasi-ganga, Sanatana Gosvami’s bhajana-kutira is near Chaklesvara Mahadeva, and at the Madana-mohana temple, near the Yamuna River in Vrindavan, his bhajana-kutira is near Gopisvara Mahadeva.

To illustrate the intimate relationship between Sanatana Gosvami and Lord Shiva, I shall relate one story. Once, at Chakra-tirtha, Sanatana Gosvami was being disturbed by mosquitoes and couldn’t do his bhajana or write his books. So he decided to leave. When Lord Shiva saw that his dear friend was about to leave, he came in the guise of a brahman and inquired, “Why are you leaving?” Sanatana Gosvami replied, “I am too disturbed by the mosquitoes and cannot do my seva.” Lord Shiva was relieved, because he knew that this was a problem he could solve. He requested Sanatana Gosvami, “Please stay one more night, and if the mosquitoes still bother you, you may go.” Then Lord Shiva summoned the demigod in charge of insect life and told him, “I don’t want any mosquitoes disturbing this great devotee here. So tell your boys to lay off.” The mosquitoes stopped coming there, and Sanatana Gosvami stayed.

The most famous and important deity of Lord Shiva for us is Gopisvara Mahadeva, established by Vajranabha near the site of the rasa dance, near Vamsivata, where Gopinatha played upon His flute to call the gopis. Gopisvara Mahadeva wanted to participate in the rasa dance, the highest and best of all of Lord Krishna’s pastimes. According to one version, Lord Shiva approached Paurnamasi, an elderly brahmani and siksa-guru of the Vrajavasis, who was the mother of Sandipani Muni, Lord Krishna’s guru. She advised Mahadeva to perform some austerities and then take bath in the Yamuna; thus he would get the form of a gopi. According to other sources, Paurnamasi directed him to Vrndadevi and Vrndadevi advised him to take bath in Mana-sarovara, a little further south across the Yamuna River from Kesi-ghata. Be it as it may, he took bath and came out in the form of a gopi.

When Krishna was about to enjoy His rasa-lila with the gopis, this new gopi appeared. The other gopis took note—“Oh, a new gopi has come”—and gathered around her. They asked, “What village are you from?” She didn’t know what to say. “What is your husband’s name?” “How many cows does he have?” “Who are your children?” She had no answers. Then the other gopis thought, “This is not a gopi. She is not one of us. This is an imposter.” They were ready to beat this imitation gopi when Mother Paurnamasi appeared and said, “This is Mahadeva Shiva. He is a great demigod. Do not take any action against him.” Then she told Lord Shiva, “No one can participate in the rasa dance without being a gopi. You can observe it from a distance, but you cannot actually enter it.” Then she gave him a service: he could guard the arena of the rasa dance. One of Lord Shiva’s regular services is to be ksetra-pala, protector of the dhama, and he serves as such in Vrindavan, Navadvipa, Jagannatha Puri, and other holy places. Paurnamasi gave Mahadeva the authority to restrain the unqualified and to admit the qualified. But beyond that, he would have the power to give someone the qualification to enter. So, devotees, Vaishnavas, in Vrindavan pray to Gopisvara Mahadeva to enable them to enter the pastimes of Krishna with the gopis.

The deity of Gopisvara Mahadeva is worshipped as a regular Shiva-linga during the day, but every evening at about four the pujaris dress the Shiva-linga like a gopi. They cover the linga with a sari and ornaments and decorate it to resemble a gopi, with a crown on it or a shawl draped over its top. And devotees come and worship Gopisvara Mahadeva to attain the favor of Radha and Krishna.

In his Sankalpa-kalpadruma (103) Srila Visvanatha Chakravarti Thakura prays:

vrndavanavani-pate jaya soma soma-

maule sanandana-sanatana-naradedya

gopisvara vraja-vilasi-yuganghri-padme

prema prayaccha nirupadhi namo namaste