Diary of a Traveling Sadhaka, Vol. 21, No. 45

By Krishna Kripa Das

(Week 45: November 5–11, 2025)

Stuyvesant Falls, Chatham, Schenectady

(Sent from Stuyvesant Falls, New York, on November 16, 2025)

Where I Went and What I Did

The forty-fifth week of 2025, I lived at Viraha Bhavan, the ashram of Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami, my Guru Maharaja, in Stuyvesant Falls, New York. I helped his caretakers with different services like cleaning the kitchen, waking up the deities, singing for Them, and uploading dictation tapes. I increased my harinama program to chanting Hare Krishna one hour on the porch on a good day. I also did some personal service for Guru Maharaja. I attended the Chatham Wednesday Program.

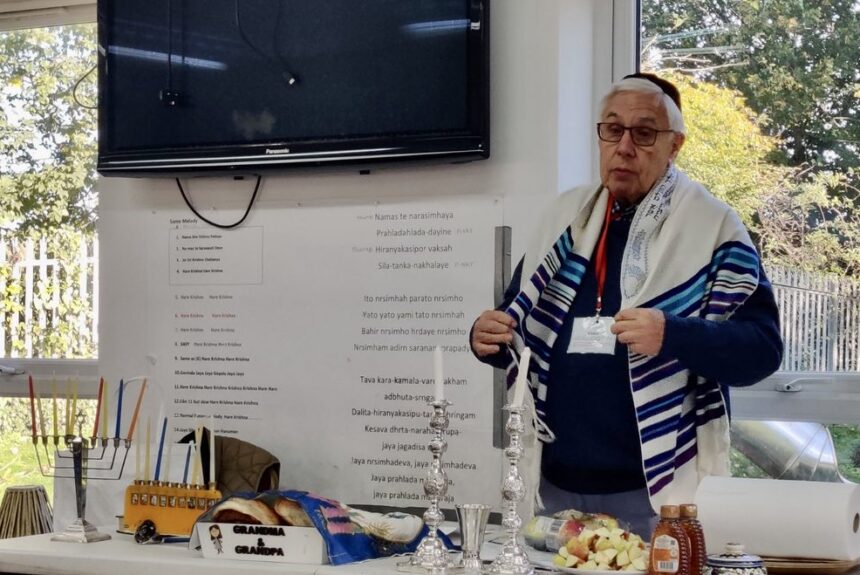

I attended the Sunday feast program at ISKCON Schenectady, where I gave a lecture on Bhagavad-gita 8.5.I share quotes from Srila Prabhupada’s Srimad-Bhagavatam, Sri Caitanya-caritamrita and The Nectar of Devotion, and also a quote from a lecture of his at 26 Second Avenue on Sri Caitanya-caritamrita in 1966. I share quotes from One-Hour Writing Sessions by Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami. I share quotes from Consciousness and the Laws of Nature and The Nature of Biological Form by Sadaputa Prabhu. I share quotes from two famous scientists quoted by Sadaputa Prabhu, Charles Darwin and Louis de Broglie.

Many thanks to Shreyakari Devi Dasi and ISKCON Schenectady for their kind donation and for the videos of their Sunday program that I took some photos from.

Itinerary

September 12–November 23: serve Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami

November 23–December 31: NYC Harinam

– December 6: Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami Vyasa-puja / Hudson Winter Walk harinama

Chanting Hare Krishna in Upstate New York

I have no videos of the Chatham program this week as I was busy playing the instruments the whole time because the usual mrdanga player did not show up.

One of the regular attenders there, Chris, told me that he lived in Guiderland, which is just 20 minutes from Schenectady, so I invited him to our ISKCON Schenectady Sunday program and he came and had a good time.

\

Here he plays karatalas behind the lead singer.

I always try to dance in the kirtans to remind people that Srila Prabhupada liked it.

Somehow the people who usually take the ghee lamp around were not there, and so I decided to do it.

I tried to include everyone, even the kids, who are always a potential challenge.One older Hindu man who regularly attends the ISKCON Schenectady Sunday program and other temples as well, shared with me this nice verse from the Ramayana, Uttarakanda 116.2, about the spiritual nature of the soul.

isvara amsa jiva avinasi

cetana amala sahaja sukha rasi

“The individual soul or jivatma, being part and parcel of the isvara or the Supersoul, possesses these attributes: avinasi (eternal), cetana (ever conscious), amala (ever pure), and sahaja sukha rasi (ever blissful).”

Photos

On the last day of Karttika, after the altar was closed for the night, I remembered I forgot to offer candles on two days of that sacred month, so I tried to make up for it.

You never know when maya will strike.Insights

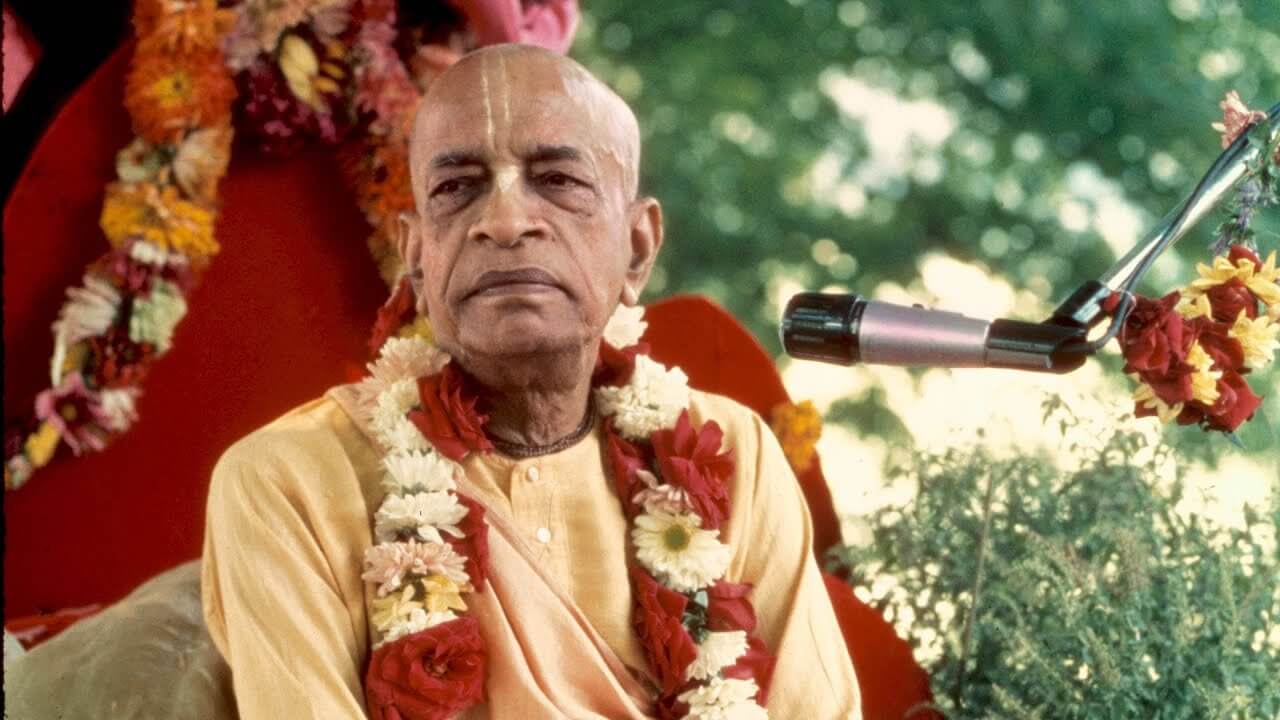

Srila Prabhupada:

From Srimad-Bhagavatam 3.23.8, purport:

“Love of God is not an ordinary commodity. Caitanya Mahaprabhu was worshiped by Rupa Gosvami because He distributed love of God, krishna-prema, to everyone. Rupa Gosvami praised Him as maha-vadanya, a greatly munificent personality, because He was freely distributing to everyone love of Godhead, which is achieved by wise men only after many, many births. Krishna-prema, Krishna consciousness, is the highest gift which can be bestowed on anyone whom we presume to love.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 7:

“In the Eleventh Canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam, Third Chapter, verse 21, Prabuddha tells Maharaja Nimi, ‘My dear King, please know for certain that in the material world there is no happiness. It is simply a mistake to think that there is happiness here, because this place is full of nothing but miserable conditions. Any person who is seriously desirous of achieving real happiness must seek out a bona fide spiritual master and take shelter of him by initiation. The qualification of a spiritual master is that he must have realized the conclusions of the scriptures by deliberation and arguments and thus be able to convince others of these conclusions. Such great personalities who have taken shelter of the Supreme Godhead, leaving aside all material considerations, are to be understood as bona fide spiritual masters. Everyone should try to find such a bona fide spiritual master in order to fulfill his mission of life, which is to transfer himself to the plane of spiritual bliss.’”

“The beginning of Krishna consciousness and devotional service is hearing, in Sanskrit called sravanam. All people should be given the chance to come and join devotional parties so that they may hear. This hearing is very important for progressing in Krishna consciousness. When one links his ears to give aural reception to the transcendental vibrations, he can quickly become purified and cleansed in the heart. Lord Caitanya has affirmed that this hearing is very important. It cleanses the heart of the contaminated soul so that he becomes quickly qualified to enter into devotional service and understand Krishna consciousness.”

“In the Fourth Canto of Srimad-Bhagavatam, Twenty-ninth Chapter, verse 39–40, the importance of hearing of the pastimes of the Lord is stated by Sukadeva Gosvami to Maharaja Pariksit: ‘My dear King, one should stay at a place where the great acaryas [holy teachers] speak about the transcendental activities of the Lord, and one should give aural reception to the nectarean river flowing from the moonlike faces of such great personalities. If someone eagerly continues to hear such transcendental sounds, then certainly he will become freed from all material hunger, thirst, fear and lamentation, as well as all illusions of material existence.’”

“Some way or other, if someone establishes in his mind his continuous relationship with Krishna, this relationship is called remembrance.”

“About this remembrance there is a nice statement in the Visnu Purana, where it is said, ‘Simply by remembering the Supreme Personality of Godhead all living entities become eligible for all kinds of auspiciousness. Therefore let me always remember the Lord, who is unborn and eternal.’”

“To meditate means to engage the mind in thinking of the form of the Lord, the qualities of the Lord, the activities of the Lord and the service of the Lord.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 12:

“A person who has relished the transcendental bliss of Srimad-Bhagavatam cannot be satisfied with mundane writings.”

“In many sastras (scriptures) it is said that simply by hearing, remembering, glorifying, desiring, seeing or touching the land of Mathura, one can achieve all desires.”

“A similar statement is in the Third Canto, Seventh Chapter, verse 19, of Srimad-Bhagavatam: ‘Let me become a sincere servant of the devotees, because by serving them one can achieve unalloyed devotional service unto the lotus feet of the Lord. The service of devotees diminishes all miserable material conditions and develops within one a deep devotional love for the Supreme Personality of Godhead.’”

“Even by remembering the activities of such a Vaisnava, one becomes purified, along with one’s whole family. And what, then, can be said of rendering direct service to him?” [SB 1.19.33]

“One should, therefore, be encouraged to develop his service attitude toward the Lord, because this will help him to chant without any offense. And so, under the guidance of a spiritual master, the disciple is trained to render service and at the same time chant the Hare Krishna mantra. As soon as one develops his spontaneous service attitude, he can immediately understand the transcendental nature of the holy names of the maha-mantra.”

“In the Vedic literature it is also stated, ‘How wonderful it is that simply by residing in Mathura even for one day, one can achieve a transcendental loving attitude toward the Supreme Personality of Godhead! This land of Mathura must be more glorious than Vaikuntha-dhama, the kingdom of God!’”

“The same thing is confirmed in the Adi Purana by Krishna. While addressing Arjuna He says, ‘Anyone who is engaged in chanting My transcendental name must be considered to be always associating with Me. And I may tell you frankly that for such a devotee I become easily purchased.’”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 15:

“Sri Rupa Gosvami has defined ragatmika-bhakti as spontaneous attraction for something while completely absorbed in thoughts of it, with an intense desire of love.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 16:

“According to the regulative principles, there are nine departmental activities, as described above, and one should specifically engage himself in the type of devotional service for which he has a natural aptitude. For example, one person may have a particular interest in hearing, another may have a particular interest in chanting, and another may have a particular interest in serving in the temple. So these, or any of the other six different types of devotional service (remembering, serving, praying, engaging in some particular service, being in a friendly relationship or offering everything in one's possession), should be executed in full earnestness. In this way, everyone should act according to his particular taste.”

“This development of conjugal love can be possible only with those who are already engaged in following the regulative principles of devotional service, specifically in the worship of Radha and Krishna in the temple. Such devotees gradually develop a spontaneous love for the Deity, and by hearing of the Lord’s exchange of loving affairs with the gopis, they gradually become attracted to these pastimes.”

“This development of conjugal love for Krishna is not manifested in women only. The material body has nothing to do with spiritual loving affairs. A woman may develop an attitude for becoming a friend of Krishna, and, similarly, a man may develop the feature of becoming a gopi in Vrindavana. How a devotee in the form of a man can desire to become a gopi is stated in the Padma Purana as follows: In days gone by there were many sages in Dandakaranya. Dandakaranya is the name of the forest where Lord Ramacandra lived after being banished by His father for fourteen years. At that time there were many advanced sages who were captivated by the beauty of Lord Ramacandra and who desired to become women in order to embrace the Lord. Later on, these sages appeared in Gokula Vrindavana when Krishna advented Himself there, and they were born as gopis, or girlfriends of Krishna. In this way they attained the perfection of spiritual life.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 17:

“It is essential, therefore, that one constantly associate with pure devotees who are engaged morning and evening in chanting the Hare Krishna mantra. In this way one will get the chance to purify his heart and develop this ecstatic pure love for Krishna.”

“In the Padma Purana there is the story of a neophyte devotee who, in order to raise herself to the ecstatic platform, danced all night to invoke the Lord’s grace upon her.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 18:

“Emperor Bharata provides a typical example of detachment. He had everything enjoyable in the material world, but he left it. This means that detachment does not mean artificially keeping oneself aloof and apart from the allurements of attachment. Even in the presence of such allurements, if one can remain unattracted by material attachments, he is called detached. In the beginning, of course, a neophyte devotee must try to keep himself apart from all kinds of alluring attachments, but the real position of a mature devotee is that even in the presence of all allurements, he is not at all attracted. This is the actual criterion of detachment.”

“The strong conviction that one will certainly receive the favor of the Supreme Personality of Godhead is called in Sanskrit asa-bandha. Asa-bandha means to continue to think, ‘Because I’m trying my best to follow the routine principles of devotional service, I am sure that I will go back to Godhead, back to home.’”

“When one is sufficiently eager to achieve success in devotional service, that eagerness is called samutkantha. This means ‘complete eagerness.’ Actually this eagerness is the price for achieving success in Krishna consciousness. Everything has some value, and one has to pay the value before obtaining or possessing it. It is stated in the Vedic literature that to purchase the most valuable thing, Krishna consciousness, one has to develop intense eagerness for achieving success.”

From The Nectar of Devotion, Chapter 19:

“In the Narada Pañcaratra it is clearly stated that when lust is completely transferred to the Supreme Godhead and the concept of kinship is completely reposed in Him, such is accepted as pure love of God by great authorities like Bhisma, Prahlada, Uddhava and Narada.

“Great authorities like Bhisma have explained that love of Godhead means completely giving up all so-called love for any other person. According to Bhisma, love means reposing one’s affection completely upon one person, withdrawing all affinities for any other person. This pure love can be transferred to the Supreme Personality of Godhead under two conditions—out of ecstasy and out of the causeless mercy of the Supreme Personality of Godhead Himself.”

“In the Narada Pañcaratra Lord Siva therefore tells Parvati, ‘My dear supreme goddess, you may know from me that any person who has developed the ecstasy of love for the Supreme Personality of Godhead, and who is always merged in transcendental bliss on account of this love, cannot even perceive the material distress or happiness coming from the body or mind.’”

From Sri Caitanya-caritamrita, Adi 1.20–21:

“In the beginning of this narration, simply by remembering the spiritual master, the devotees of the Lord, and the Personality of Godhead, I have invoked their benedictions. Such remembrance destroys all difficulties and very easily enables one to fulfill his own desires.”

From Sri Caitanya-caritamrita, Adi 1.35:

“If one desires unalloyed devotional service, one must associate with devotees of Sri Krishna, for by such association only can a conditioned soul achieve a taste for transcendental love and thus revive his eternal relationship with Godhead in a specific manifestation and in terms of the specific transcendental mellow (rasa) that one has eternally inherent in him.”

“One should always remember that a person who is reluctant to accept a spiritual master and be initiated is sure to be baffled in his endeavor to go back to Godhead. One who is not properly initiated may present himself as a great devotee, but in fact he is sure to encounter many stumbling blocks on his path of progress toward spiritual realization, with the result that he must continue his term of material existence without relief. Such a helpless person is compared to a ship without a rudder, for such a ship can never reach its destination. It is imperative, therefore, that one accept a spiritual master if he at all desires to gain the favor of the Lord. The service of the spiritual master is essential. If there is no chance to serve the spiritual master directly, a devotee should serve him by remembering his instructions. There is no difference between the spiritual master’s instructions and the spiritual master himself. In his absence, therefore, his words of direction should be the pride of the disciple. If one thinks that he is above consulting anyone else, including a spiritual master, he is at once an offender at the lotus feet of the Lord. Such an offender can never go back to Godhead. It is imperative that a serious person accept a bona fide spiritual master in terms of the sastric [scriptural] injunctions.”

From Sri Caitanya-caritamrita, Adi 1.46, purport:

“A spiritual master is not an enjoyer of facilities offered by his disciples. He is like a parent. Without the attentive service of his parents, a child cannot grow to manhood; similarly, without the care of the spiritual master one cannot rise to the plane of transcendental service.”

From a lecture on Sri Caitanya-caritamrita, Madhya 20.245–255 in New York on December 17, 1966:

“When there is too much foolishness, so there is need of avatara, incarnation, to correct. Yada yada hi dharmasya glanir bhavati. Whenever there is, I mean to say, discrepancies in the maintenance of law and order of this material nature, there is need of avatara, incarnation. Because it is God’s kingdom, it is also secondary kingdom—real kingdom in the spiritual world—so God comes in different avatara.”

“We are seeing that a flower is being produced automatically, so nicely painted, so nicely colored. But because we are fools, therefore we think it is being produced automatically. No. It is produced by the kriya-sakti, by the active potency of God, kriya-sakti. Jñana-sakti: and there is such perfect knowledge that nobody can see any defect.”

Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami:

From One-Hour Writing Sessions:

“The Hindi lecturer over the P.A. system is listened to by his immediate audience, but also by 250 squirrels and two billion ants.”

“He said I think there is a bacterium in Vrindavana with my name on it, and it’s just a matter of time until it catches up to me.”

“You are sad there is nothing new, can’t change yourself or the world quicker than it’s already changing. Better accept what comes, and let it flow through you.”

Sadaputa Prabhu:

From Consciousness and the Laws of Nature (Bhaktivedanta Institute Monograph 3), Chapter 1:

“Since the time of Newton all major scientific theories of nature have been

characterized by two assumptions:

(1) All of the significant features of nature can be described by

numbers.

(2) All of the phenomena of nature are governed by laws which can

be described by very simple mathematical equations relating

these numbers to one another.

Furthermore, throughout the history of modern science, scientists have strongly

tended to assume that all phenomena can be accounted for (at least in principle)

by the accepted laws of their day.

These assumptions form the foundation for the modern scientific view of

the absolute truth. The absolute truth can be defined as the ultimate causative

principle or agency underlying all of the phenomena of nature; and the understanding

of this fundamental cause can be seen as the goal of all fundamental

research in science. However, conditions (1) and (2) impose a very severe a

priori restriction on the nature of the absolute truth. There is no particular

reason to suppose that every significant feature of nature can be described

by numbers, or that those which can be so described are governed by simple

equations. Our thesis is that nature cannot actually be understood within the

framework imposed by these conditions.”

“We are proposing that the phenomenon of consciousness cannot be described by numbers, and that the behavior of matter is less and less amenable to description by simple equations the more intimately it is associated with consciousness.”

“Just as the electrons interact with other matter through the agency of the electric

field (in the standard theory), so the individual conscious entities, or ‘quanta’

of consciousness, interact with matter through the agency of absolute consciousness.”

From Consciousness and the Laws of Nature (Bhaktivedanta Institute Monograph 3), Chapter 7:

“The basic philosophical presupposition of modern science is that all the

effects of nature are the consequences of a few simple laws capable of mathematical

expression. Our thesis is that this presupposition has by no means

been established. Indeed, as stated by the physicist D. Bohm in a discussion of

this point, ‘the historical development of physics has not confirmed the basic

assumptions of this philosophy, but rather has continually contradicted them.’”

“Throughout its struggles with the nature of matter, modern science has neglected

consciousness almost completely, even though this phenomenon is the most

primary feature of our existence as living beings. Indeed, the very existence of

consciousness has proven to be a great embarrassment to the theoreticians of

quantum mechanics. Some physicists, such as Niels Bohr, have been content to ignore, or “renounce,” the very question of understanding consciousness.

“Others, such as von Neumann and Wigner, have recognized that consciousness

lies outside the domain of their theories, but must be taken into account if a

true understanding of nature is to be reached. However, they have not been able

to introduce consciousness into their theoretical picture in a satisfactory way.”

“From a calculated list of numbers corresponding to some physical behavior, what can we say about the awareness that may or may not have been associated with that behavior? It remains a complete mystery.”

“The theory of quantum mechanics has left our understanding of matter rather ‘fuzzy’ to say the least. It is capable to some extent of being described by various mathematical laws. However, it is evident that matter is still in many respects a mystery to modern science.”

From The Nature of Biological Form:

“While evolutionists often speak of changes in the size and shape of existing organs, they still can do very little but make vague suggestions about the origin of the organs themselves.”

“The geneticist Richard Goldschmidt once gave a list of seventeen organs and systems of organs for which he could not even imagine the required transitional forms. This list included hair in mammals, feathers in birds, the segmented structure of vertebrates, teeth, the external skeletons and compound eyes of insects, blood circulation, and the organs of balance.”

Charles Darwin:

From On the Origin of Species:

“If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications. my theory would absolutely break down.”

Louis de Broglie, French theoretical physicist:

[Quoted in Consciousness and the Laws of Nature, Bhaktivedanta Institute Monograph 3, by Sadaputa Prabhu]

“It is premature to reduce the vital process to the quite insufficiently developed conception of 19th and even 20th century chemistry and physics.”

-----

Remembrance of the Supreme Lord frees us from our karma (Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.2.15) and helps awaken the love of God dormant in our spiritual self. This remembrance of the Lord is so wonderfully auspicious that this verse appears in the Vishnu Purana:

sa hanis tan mahac chidram

sa mohah sa ca vibhramah

yan-muhurtam kñanam vapi

vasudevam na cintayet

“If even for a moment remembrance of Vasudeva, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, is missed, that is the greatest loss, that is the greatest illusion, and that is the greatest anomaly.” (quoted in Srimad-Bhagavatam 2.9.36, purport)

Don’t make that mistake!

By Sri Nandanandana dasa (Stephen Knapp) Not long ago I was giving a lecture to a general audience of Indians, with many Krishna devotees in the crowd. In the lecture, I raised the principle of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, or how “the whole world is one family.” Yet many devotees had not heard of this phrase before,

By Sri Nandanandana dasa (Stephen Knapp) Not long ago I was giving a lecture to a general audience of Indians, with many Krishna devotees in the crowd. In the lecture, I raised the principle of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, or how “the whole world is one family.” Yet many devotees had not heard of this phrase before,

Dear Godbrothers, Godsisters, and well-wishers of HH Niranjana Swami, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada. Two days ago, Maharaja had an angiography performed in Kolkata to determine the extent of blockage in his arteries. The result of the procedure showed that there is significant blockage in three of his arteries. To

Dear Godbrothers, Godsisters, and well-wishers of HH Niranjana Swami, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada. Two days ago, Maharaja had an angiography performed in Kolkata to determine the extent of blockage in his arteries. The result of the procedure showed that there is significant blockage in three of his arteries. To Witness the latest progress of the Temple of the Vedic Planetarium as TOVP presents the November 2025 Construction Update of the Main Wing. In this video H.G. Braja Vilasa prabhu, TOVP Vice Chairman, will give you a detailed look at the ongoing developments, structural advancements, and the milestones reached as the TOVP moves closer to

Witness the latest progress of the Temple of the Vedic Planetarium as TOVP presents the November 2025 Construction Update of the Main Wing. In this video H.G. Braja Vilasa prabhu, TOVP Vice Chairman, will give you a detailed look at the ongoing developments, structural advancements, and the milestones reached as the TOVP moves closer to By Premanjana Das Stephen Knapp, also known by his spiritual name Sri Nandanandana Dasa (Śrī Nandanandana Dāsa), is an American author, spiritual practitioner, researcher, and lecturer on Vedic culture (Sanātana Dharma) and philosophy. He is associated with the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) and is a disciple of A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Knapp

By Premanjana Das Stephen Knapp, also known by his spiritual name Sri Nandanandana Dasa (Śrī Nandanandana Dāsa), is an American author, spiritual practitioner, researcher, and lecturer on Vedic culture (Sanātana Dharma) and philosophy. He is associated with the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) and is a disciple of A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. Knapp By Matsya Avatar Das

By Matsya Avatar Das

By Radha Mohan Das National Interfaith Week provided a wonderful opportunity for the children of Gurukula – The Hare Krishna Primary School to deepen their appreciation of other faith traditions while grounding their learning in Vaishnava values of respect, empathy, and unity. Across the school, students took part in meaningful visits, thoughtful discussions, and inspiring

By Radha Mohan Das National Interfaith Week provided a wonderful opportunity for the children of Gurukula – The Hare Krishna Primary School to deepen their appreciation of other faith traditions while grounding their learning in Vaishnava values of respect, empathy, and unity. Across the school, students took part in meaningful visits, thoughtful discussions, and inspiring Are there no torn clothes lying on the common road? Do the trees, which exist for maintaining others, no longer give alms in charity? Do the rivers, being dried up, no longer supply water to the thirsty? Are the caves of the mountains now closed? Or above all, does the Almighty Lord not protect the

Are there no torn clothes lying on the common road? Do the trees, which exist for maintaining others, no longer give alms in charity? Do the rivers, being dried up, no longer supply water to the thirsty? Are the caves of the mountains now closed? Or above all, does the Almighty Lord not protect the In the Bhakti tradition, we learn that there are three desires which spring forth from the soul and which can be fulfilled by a very special personality: the desire to see the divine rasa dance, to attain the kingdom of the Lord — the eternal spiritual world, Vrindavan — and to lovingly serve the divine

In the Bhakti tradition, we learn that there are three desires which spring forth from the soul and which can be fulfilled by a very special personality: the desire to see the divine rasa dance, to attain the kingdom of the Lord — the eternal spiritual world, Vrindavan — and to lovingly serve the divine Discover the construction of our new eco-house in New Mayapur. Built with 220 locally sourced straw bales on a wooden structure, this low-carbon design offers durability and high thermal resistance. The oak and pine beams come directly from the New Mayapur forest, combining traditional techniques with modern technology. This project uses both concrete and foundation

Discover the construction of our new eco-house in New Mayapur. Built with 220 locally sourced straw bales on a wooden structure, this low-carbon design offers durability and high thermal resistance. The oak and pine beams come directly from the New Mayapur forest, combining traditional techniques with modern technology. This project uses both concrete and foundation

Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada! This month Mayapur, Mumbai-Juhu, and Bhaktivedanta Manor were the top three large temples. Ahmedabad, Bengaluru-South and London-Soho were the top three medium temples. Chandigarh, Surat and Toronto were the top small temples and Calgary, Madrid and Kishinev were the top maha-small temples this month. Over

Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada! This month Mayapur, Mumbai-Juhu, and Bhaktivedanta Manor were the top three large temples. Ahmedabad, Bengaluru-South and London-Soho were the top three medium temples. Chandigarh, Surat and Toronto were the top small temples and Calgary, Madrid and Kishinev were the top maha-small temples this month. Over While some may think that building the TOVP is just building another temple, this is far from the truth. In reality, it is the greatest act of compassion upon Building the TOVP – The Supreme Act of Compassion – Temple of the Vedic Planetarium

While some may think that building the TOVP is just building another temple, this is far from the truth. In reality, it is the greatest act of compassion upon Building the TOVP – The Supreme Act of Compassion – Temple of the Vedic Planetarium We actually do not die. At death, we are merely kept inert for some time, just as during sleep. At night we sleep, and all our activities stop, but as soon as we arise, our memory immediately returns, and we think, “Oh, where am I? What do I have to do?” This is called suptotthita-nyāya.

We actually do not die. At death, we are merely kept inert for some time, just as during sleep. At night we sleep, and all our activities stop, but as soon as we arise, our memory immediately returns, and we think, “Oh, where am I? What do I have to do?” This is called suptotthita-nyāya. Standing on his chariot, Arjuna took up his bow and drove off the valiant fighters and palace guards who tried to block his way. As her relatives shouted in anger, he took Subhadrā away just as a lion takes his prey from the midst of lesser animals. H.G. Tejo Prakash Prabhu || SB – 10.86.10

Standing on his chariot, Arjuna took up his bow and drove off the valiant fighters and palace guards who tried to block his way. As her relatives shouted in anger, he took Subhadrā away just as a lion takes his prey from the midst of lesser animals. H.G. Tejo Prakash Prabhu || SB – 10.86.10

By Partha Sarathi Das Goswami Gokulendra Prabhu, also known as Greg, met Ksudhi Prabhu either in 1972 or 1973. At that time, he was a student at Rhodes University, which was then one of the most prestigious universities in South Africa. Greg would finish his lectures on a Friday night and would hitchhike all the

By Partha Sarathi Das Goswami Gokulendra Prabhu, also known as Greg, met Ksudhi Prabhu either in 1972 or 1973. At that time, he was a student at Rhodes University, which was then one of the most prestigious universities in South Africa. Greg would finish his lectures on a Friday night and would hitchhike all the Anuttama Prabhu begins with light-hearted remarks and kirtan, then reads and explains Srimad Bhagavatam 3.31.14, where the soul in the womb prays to the Lord, realizing its separation from Him due to being trapped in a material body made of the five elements. Main Themes The Soul and the Lord The soul (jiva) is spiritual

Anuttama Prabhu begins with light-hearted remarks and kirtan, then reads and explains Srimad Bhagavatam 3.31.14, where the soul in the womb prays to the Lord, realizing its separation from Him due to being trapped in a material body made of the five elements. Main Themes The Soul and the Lord The soul (jiva) is spiritual And I’m like oh okay this is nice. Some people are rejecting me. This is nice. Why is it nice? Because sometimes we think oh yeah I know something. I know a few shlokas right? I can do this and then people say hey get out of my way you know like I’m not interested

And I’m like oh okay this is nice. Some people are rejecting me. This is nice. Why is it nice? Because sometimes we think oh yeah I know something. I know a few shlokas right? I can do this and then people say hey get out of my way you know like I’m not interested The process is simple. But the application is difficult. Most people they like to hear about the political conversations the news but when invited to attend a meeting of the Shrimage Bavatam you people don’t come. So we must try to convince them from the be and those who are interested. They they find that

The process is simple. But the application is difficult. Most people they like to hear about the political conversations the news but when invited to attend a meeting of the Shrimage Bavatam you people don’t come. So we must try to convince them from the be and those who are interested. They they find that With great respect, King Rantideva offered the balance of the food to the dogs and the master of the dogs, who had come as guests. The King offered them all respects and obeisances. Thereafter, only the drinking water remained, and there was only enough to satisfy one person, but when the King was just about

With great respect, King Rantideva offered the balance of the food to the dogs and the master of the dogs, who had come as guests. The King offered them all respects and obeisances. Thereafter, only the drinking water remained, and there was only enough to satisfy one person, but when the King was just about While recuperating from his stroke at Stinson Beach near San Francisco, Srila Prabhupada found the climate unsuitable due to insufficient sunlight. Deciding to return to India for better health, he planned a route from San Francisco → New York → London → Moscow → Delhi. Initiations at Stinson Beach Unable to travel to the temple

While recuperating from his stroke at Stinson Beach near San Francisco, Srila Prabhupada found the climate unsuitable due to insufficient sunlight. Deciding to return to India for better health, he planned a route from San Francisco → New York → London → Moscow → Delhi. Initiations at Stinson Beach Unable to travel to the temple Having achieved love of Godhead, the devotees sometimes weep loudly, absorbed in thought of the infallible Lord. Sometimes they laugh, feel great pleasure, speak out loud to the Lord, dance or sing. Such devotees, having transcended material, conditioned life, sometimes imitate the unborn Supreme by acting out His pastimes. And sometimes, achieving His personal audience,

Having achieved love of Godhead, the devotees sometimes weep loudly, absorbed in thought of the infallible Lord. Sometimes they laugh, feel great pleasure, speak out loud to the Lord, dance or sing. Such devotees, having transcended material, conditioned life, sometimes imitate the unborn Supreme by acting out His pastimes. And sometimes, achieving His personal audience, Chanting the holy name of Krishna is the highest spiritual process. In Kali-yuga, the Lord has made the path simple: through sankirtan one can achieve peace, liberation, and pure love of God, surpassing all other methods of previous ages. The true devotee does not seek release from suffering but only the privilege of serving and

Chanting the holy name of Krishna is the highest spiritual process. In Kali-yuga, the Lord has made the path simple: through sankirtan one can achieve peace, liberation, and pure love of God, surpassing all other methods of previous ages. The true devotee does not seek release from suffering but only the privilege of serving and