Thursday, November 28th, 2019

Wednesday, November 27th, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

Tuesday, November 26th, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

Monday, November 25th, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

ISKCON Scarborough – Gita Jayanti – The appearance day celebration of Srimad Bhagavad Gita – Saturday- December 7th 2019

→ ISKCON Scarborough

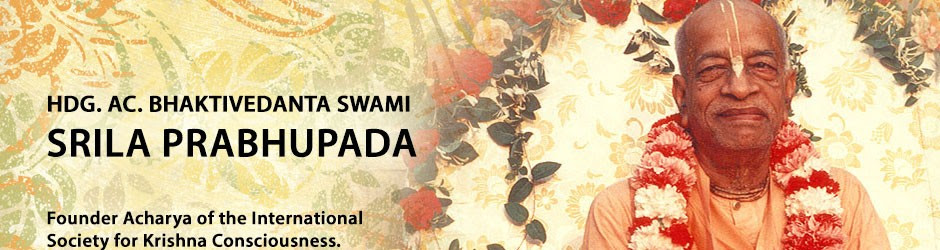

Please accept our humble obeisances!

All glories to Srila Prabhupada!

All glories to Sri Guru and Sri Gauranga!

We have two very auspicious events happening on the same day coming Saturday- Dec 7th 2019.

- Advent of Srimad Bhagavad-Gita (Gita Jayanti)

- Moksada Ekadasi

One of the Vrata(vow) undertaken during Ekadasi is to read the Holy Scriptures.

What can be more glorious on this Moksada Ekadasi than reading Bhagavad Gita on the very day that marks the 5156th appearance day anniversary?

We at ISKCON Scarborough will be celebrating Gita Jayanti in a grand manner by reading all the 700 English verses starting at 6.30 PM sharp!

The advent of Srimad Bhagavad-Gita(Gita Jayanti)

It was on this day 5156 years ago, that Sanjaya narrated to King Dhritarashtra the dialogue between Sri Krishna and Arjuna in the battlefield of Kurukshetra at the place now known as Jyotisha tirtha, and thus made the glorious teachings of the Lord available to the people of the world, for all time.

Srimad Bhagavad-Gita shows a way to rise above the world of duality and the pairs of opposites and to acquire eternal bliss and immortality. It is a gospel of action. It teaches the rigid performance of one's duty in society and a life of active struggle, keeping the inner being untouched by outer surroundings and renouncing the fruits of actions as offerings unto the Lord.

Srimad Bhagavad-Gita is a source of power and wisdom. It strengthens us when you are weak, and inspires us when you feel dejected and feeble. It teaches us how to resist unrighteousness and follow the path of virtue and righteousness.

The teachings of the Gita are broad, sublime and universal. They do not belong to any sect, creed, age, place or country. They are meant for all. They are within the reach of all. The Gita has a message for the solace, peace, freedom, salvation and perfection of all human beings.

Anyone who gifts a Bhagavad-Gita to a deserving person on this day is bestowed profuse blessings by Lord Krsna

There will be a grand Ekadasi feast served after the whole recitation.

On the auspicious occasion, we welcome you, your family and friends to join us at ISKCON Scarborough to recite the entire Gita verses and to partake the unlimited blessing of Sri Sri Radha Gopi Vallabha.

ISKCON Scarborough

3500 McNicoll Avenue, Unit #3,

Scarborough, Ontario,

Canada, M1V4C7

Email Address:

iskconscarborough@hotmail.com

scarboroughiskcon@gmail.com

website: www.iskconscarborough.org

Tasting and Distributing Krishna Consciousness: December Marathon Message

Giriraj Swami

We have again reached December, that most auspicious time of year when the book-distribution marathon takes place. In honor of the occasion, I quote two verses from Srimad-Bhagavatam that embody the devotee’s mood in distributing Krishna consciousness.

We have again reached December, that most auspicious time of year when the book-distribution marathon takes place. In honor of the occasion, I quote two verses from Srimad-Bhagavatam that embody the devotee’s mood in distributing Krishna consciousness.

naivodvije para duratyaya-vaitaranyas

tvad-virya-gayana-mahamrta-magna-cittah

soce tato vimukha-cetasa indriyartha-

maya-sukhaya bharam udvahato vimudhan

“O best of the great personalities, I am not at all afraid of material existence, for wherever I stay I am fully absorbed in thoughts of Your glories and activities. My concern is only for the fools and rascals who are making elaborate plans for material happiness and maintaining their families, societies, and countries. I am simply concerned with love for them.” (SB 7.9.43)

prayena deva munayah sva-vimukti-kama

maunam caranti vijane na parartha-nisthah

naitan vihaya krpanan vimumuksa eko

nanyam tvad asya saranam bhramato ’nupasye

“My dear Lord Nrsimhadeva, I see that there are many saintly persons indeed, but they are interested only in their own deliverance. Not caring for the big cities and towns, they go to the Himalayas or the forest to meditate with vows of silence [mauna-vrata]. They are not interested in delivering others. As for me, however, I do not wish to be liberated alone, leaving aside all these poor fools and rascals. I know that without Krsna consciousness, without taking shelter of Your lotus feet, one cannot be happy. Therefore I wish to bring them back to shelter at Your lotus feet.” (SB 7.9.44)

To distribute Krishna consciousness, we must have Krishna consciousness. These verses are about Prahlada Maharaja, and in a way they are also about Srila Prabhupada, who in his purport expressed his own mood—and about us, how Srila Prabhupada wants us to execute Krishna consciousness. Prahlada Maharaja and Srila Prabhupada were each on a very high level of Krishna consciousness, but even on our own level we can experience something of what they experienced, that wherever we are we can get relief from material miseries and anxieties by taking shelter of the holy name. We can joyfully chant in the temple room, in the association of devotees, before the Deities, and in the presence of Tulasi-devi—but one can chant anywhere, even on traveling sankirtana. One can close one’s eyes and chant and hear and no longer be in the material world—actually be with Krishna.

Devotees need that connection with Krishna not just for their own sakes but also for the sake of others. Once, in a meeting with Srila Prabhupada in the Atlanta temple, Svavasa Prabhu asked, “How can we increase our devotion and our desire to distribute more books?” He and the other devotees were eagerly anticipating some special formula to expand their book distribution. Srila Prabhupada didn’t look at them; he looked upward, as they waited in suspense. Finally he said, “If you want to increase book distribution, if you really want, I have only one recommendation. . . . You must chant your rounds uninterrupted. After you begin your chanting, do not stop until you finish.” As Svavasa Prabhu explained, if you win that fight, you will win all day, but if you lose it and allow your mind to carry you to something else, you will have a difficult day.

Svavasa Prabhu still follows that policy. He gets up at two in the morning and chants all his rounds before even coming to the temple for mangala-arati. A while ago I stayed with Vaisesika Prabhu at his home in Burlingame, and his morning program was blissfully intense. He did things that we do every day—and some things that we may do only on occasion—but he did them with so much enthusiasm and so much relish that the practices came to life. I felt, “Wow, that’s what reciting these verses and prayers actually is.” We spoke later about the book he was writing on book distribution, and he said that one of the themes was that the energy to distribute books comes from the overflow of the ecstasy we feel from our spiritual practices, from our own Krishna consciousness.

I’ve also experienced that if you chant your rounds in the morning before going out you will get extra energy and intelligence for your service, and if you don’t, not only may you be a little depleted in your spiritual energy, but you may also be in anxiety about when you’re going to finish your rounds.

So this practice of rising early and chanting all your rounds is very much part of the process of sharing Krishna consciousness with others. In the first verse, Prahlada said that he has no anxiety for himself because wherever he is he can merge himself into the nectarean ocean of Krishna consciousness—and that’s true for us as well. Wherever we go, we can have that experience of tasting the nectar of Krishna consciousness by chanting the holy names and by reading, studying, and discussing Srila Prabhupada’s books.

So the two—tasting and distributing—go together. Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura said that the best gosthyanandi is a bhajananandi who likes to preach. Gosthyanandi means someone who takes pleasure in preaching and sharing Krishna consciousness with others, and a bhajananandi is someone who takes pleasure in his own bhajana, his own spiritual practices. Prahlada Maharaja exemplifies that principle, because personally he can experience pure bliss anywhere at any time just by chanting and hearing and remembering his Lord. Yet he is not content to go back home, back to Godhead, alone; he wants to bring the krpanan with him.

Krpana is a very significant word. It is discussed by Srila Prabhupada in the Bhagavad-gita, in relation to Arjuna’s admission that he was overcome by miserly weakness.

karpanya-dosopahata-svabhavah

prcchami tvam dharma-sammudha-cetah

yac chreyah syan niscitam bruhi tan me

sisyas te ’ham sadhi mam tvam prapannam

“Now I am confused about my duty and have lost all composure because of miserly weakness. In this condition I am asking You to tell me for certain what is best for me. Now I am Your disciple, and a soul surrendered unto You. Please instruct me.” (Gita 2.7)

Krpana means “miser.” But how does it apply? A miser is someone who has an asset but doesn’t use it. He may have a lot of money but not spend it for any good purpose; he will just hoard it. So, we have this human form of life, which is extremely rare and valuable—valuable because it can be used to realize God. And if we don’t use it for that purpose, we are krpanas, misers.

labdhva su-durlabham idam bahu-sambhavante

manusyam artha-dam anityam apiha dhirah

turnam yateta na pated anu-mrtyu yavan

nihsreyasaya visayah khalu sarvatah syat

“After many, many births one achieves the rare human form of life, which, although temporary, affords one the opportunity to attain the highest perfection. Thus a sober human being should quickly endeavor for the ultimate perfection of life before his body, which is always subject to death, falls away. After all, sense gratification is available even in the most abominable species of life, whereas Krsna consciousness is possible only for a human being.” (SB 11.9.29)

And not only do we have this form of life, but we have the knowledge of Krishna consciousness, which is most valuable, and we should not keep that knowledge to ourselves; we should distribute it.

Of course, preaching directly about Krishna can sometimes be an austerity. As Srila Prabhupada said, “If you tell people ‘Give up all your nonsense and just surrender to Krishna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead,’ they might not like it. A few might, but most probably won’t.” And the same applies to distributing books. It can be an austerity, because people don’t like the message of Krishna consciousness. They came into the material world to be God, and they don’t want to hear that someone else is God and that they have to surrender to Him. But if we can get them to take a book, the book will tell them. Some time ago, I was visiting a nice devotee family, and the mother’s mother, who was visiting from India, was a pious lady and was very respectful and appreciative of devotees but expressed some wild, impersonalist ideas. I thought, “What am I going to do?” We were having a nice visit, the fulfillment of my hosts’ long-cherished desire, and everyone was very happy. If I contradicted her it could have led to an argument and had a bad effect. But I couldn’t just let the comments stand.

So I prayed to Prabhupada in my heart, and I got the answer: “Just be polite and pleasant, and I’ll preach to her; I’ll correct her.” Without challenging anything the grandmother had said, I asked, “Have you read Srila Prabhupada’s books?” And we concluded that she would begin to study them regularly.

In these verses we find words that Srila Prabhupada uses quite frequently: “fools” and “rascals.” If you take the meaning of krpana to its deepest level, it comes to fool and rascal, and in the earlier verse vimudhan literally means “fool.” In many places Krishna uses these words—avajananti mam mudha, na mam duskrtino mudhah. They are in the scriptures, but it may not work well if we use them with the people we are trying to attract to Krishna consciousness. Again, here’s where the books come in. We don’t have to call people fools and rascals; we give them the books, and the books will call them fools and rascals. And they need to hear it, whether in those terms or not.

His Holiness Rtadhvaja Swami used to distribute books at Florida Welcome Centers. People would park and get out of their cars, and in one case the wife went into the welcome center and the husband stayed in the parking lot. Rtadhvaja Swami handed him a Bhagavatam. “What’s this about?” the man asked. “It has ancient teachings on yoga and meditation,” Maharaja replied. “Oh, that sounds interesting.” So, the man opened the book, and the first thing he read was, “persons . . . averse to the nectar of the activities of the Supreme Personality of Godhead . . . are compared to stool-eating hogs.” He asked Maharaja, “What does this have to do with yoga?” Just then, his wife came out and said, “Honey, what do you have there? What are you talking about?” “Oh, nothing, Honey,” he replied, and then he closed the book, handed Maharaja a donation, and walked away with the book, smiling. Although he didn’t want his wife to know he was being accused of being like a “stool-eating hog,” he wanted to hear it.

Once, Bhurijana Prabhu, knowing how some devotees can be sensitive to strong language, played a short excerpt in which Prabhupada used the word “rascal” seven times. And each time Prabhupada used the word, Bhurijana would say, “First time,” then “Second time,” then “Third time,” all the way through. He was aware of what Prabhupada had been doing, and in that little three- or four-minute excerpt Prabhupada had used the word “rascal” seven times—because pleasant or unpleasant, that’s what we need to hear.

Sometimes readers have noted that there is repetition in Prabhupada’s books. By ordinary literary standards, there shouldn’t be repetition, but Prabhupada himself said, “It is not enough to say that Krishna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead in one purport; we will say that Krishna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead in every purport.” So, there may be repetition, and there may be strong language, but the books have everything, and if someone is sincere he or she will get what he or she needs from them. The books have made so many devotees, they are making devotees now, and they will continue to make devotees in the future.

So yes, “Distribute books! Distribute books! Distribute books!” And to get the strength to do that, chant and hear and be steady in your spiritual practices—and read the books. As Srila Prabhupada said, “Distributing my books will keep them [the devotees] happy, and reading my books will keep them.” He has given us everything, but we have to take advantage, we have to do what he said, and if we do, we will get the results and everyone will be happy.

Yours in service,

Giriraj Swami

Odana-Sasthi -The first day of winter!

→ Mayapur.com

Today is the festival of Odana-sasthi. This ceremony indicates that from that day forward, a winter covering should be given to Lord Jagannatha*.” – Sri Caitanya Caritamrta, Madhya-lila16.79, purport Once, Srila Pundarika Vidyanidhi and Srila Svarupa Damodara came to Jagannatha Puri and saw the festival of odana-sasthi. On this day, the Lord is offered […]

The post Odana-Sasthi -The first day of winter! appeared first on Mayapur.com.

How to Become Qualified to See God?

→ ISKCON News

Establishing Structured Spiritual Education in Modern Times

→ ISKCON News

Odana-sasthi and Pundarika Vidyanidhi

Giriraj Swami

Today is Odana-sasthi, the date on which Lord Jagannatha is given a winter shawl. One year, when Lord Chaitanya and His associates celebrated this festival in Puri, Pundarika Vidyanidhi, who is Vrsabhanu Maharaja, Srimati Radharani’s father, in krsna-lila, received some special mercy. His experience is instructive for us all.

Today is Odana-sasthi, the date on which Lord Jagannatha is given a winter shawl. One year, when Lord Chaitanya and His associates celebrated this festival in Puri, Pundarika Vidyanidhi, who is Vrsabhanu Maharaja, Srimati Radharani’s father, in krsna-lila, received some special mercy. His experience is instructive for us all.

Srila Prabhupada explains, “At the beginning of winter, there is a ceremony known as the Odana-sasthi. This ceremony indicates that from that day forward, a winter covering should be given to Lord Jagannatha. That covering is directly purchased from a weaver. According to the arcana-marga, a cloth should first be washed to remove all the starch, and then it can be used to cover the Lord. Pundarika Vidyanidhi saw that the priest neglected to wash the cloth before covering Lord Jagannatha. Since he wanted to find some fault in the devotees, he became indignant.” (Cc Madhya 16.78 purport)

And Sri Caitanya-caritamrta (Madhya 16.78–81) describes the event: “Pundarika Vidyanidhi initiated Gadadhara Pandita for the second time, and on the day of Odana-sasthi Pundarika Vidyanidhi saw the festival. When Pundarika Vidyanidhi saw that Lord Jagannatha was given a starched garment, he became a little hateful. In this way his mind was polluted. That night the brothers Lord Jagannatha and Balarama came to Pundarika Vidyanidhi and, smiling, began to slap him. Although his cheeks were swollen from the slapping, Pundarika Vidyanidhi was very happy within. This incident has been elaborately described by Thakura Vrndavana dasa.”

From this incident, we can learn that the Lord does not tolerate offenses against His servants, even from an advanced devotee, and that He chastises any devotee who commits such an offense even within the mind. We can also learn that a pure devotee accepts such chastisement from the Lord with great happiness, as a manifestation of the Lord’s mercy, of His love and care for His devotees—both for those who may commit such an offense and for those who may be objects of such an offense. He thanks the Lord for rectifying him and preventing him from committing further offenses, and he feel great jubilation within his heart.

Hare Krishna.

Yours in service,

Giriraj Swami

What is the Vedic perspective on euthanasia?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

From: Vikas Dhawan

request you to please let me know the vedic perspective on euthanasia (mercy killing). is it allowed? from SB we know that Bhisma dev had the benediction that he will leave his body only on his own accord at a time that he desired, however in euthanasia the patient is not capable enough of making a rationale decision on whether to live or leave the body. how should we understand this from a vedic perspective.

Thanks a lot for taking the time to clarify my doubts.

Transcribed by: Dr Suresh Gupta

Edited by: Sharan Shetty

Question: What is the Vedic perspective on euthanasia? Can the passing away of Bhishma pitamah be called as euthanasia?

Answer: The example of Bhisma pitamah is not really relevant to euthanasia. In euthanasia, a person wants to end life unnaturally and prematurely in order to avoid incurable pain. In contrast, Bhishma pitamah, although he was in pain, still wanted to prolong his life so that he could see the prosperity of his grandsons, the Pandavas. The above two principles are radically different. Bhishma had the advantage to reduce his pain by departing from his body on the tenth day of Mahabharata war when he fell. However, he stayed on for a higher purpose despite pain. On the other hand, in euthanasia, people want to cut short their lives.

From the Vedic perspective euthanasia is certainly not acceptable. We are given the body due to our past karma and we have to live in this body for a particular period of time. In that period, we have to endure certain amount of karmic reactions. If we try to avoid them by prematurely destroying the body, then all that we gain is more karmic reactions to endure.

We endure more karmic reactions because we destroyed the body prematurely which was entrusted to us by God. It is like a suicide, which is sinful. It may seem like an easy escape from sufferings, but it is important to understand that we cannot evade sufferings by prematurely destroying the body. We will get a future body to endure those sufferings, and suicide only makes it worse because now we have to suffer even more. That is why the concept of euthanasia or mercy killing is certainly not acceptable.

According to some surveys, actually it is not “mercy killing” rather it is “convenience killing”. The person may want to live but the person’s relatives or the support staff do not want to take care of the person anymore. For the sake of convenience, often the person is given some injection to end the life.

Vedic understanding is that let nature follow its course. We do not accelerate death by taking some substances because that is nothing but a medically assisted suicide. On the other hand, Vedic philosophy also does not recommend prolonging life using artificial support systems for a very long time. When the doctors say there is not much chance of recovery and the body is in a dysfunctional state then keeping the support system is not recommended. Srila Prabhupada has explained how we are a spirit soul in a material body and if the body has become dysfunctional, the soul has to go to a new body. There is no need to stay attached.

There is another question to a similar topic whose answer you can find on this website,

Can we extend our lives by medicines?

There is one kind of voluntarily accepted death which might seem like euthanasia, but it is different. It is called prayavrata which means a person decides to fast to death. Prayavrata may seem like euthanasia or suicide but on the contrary it is a religious way of departing from the body. When a person feels he has no desire to live (out of intense material detachment or spiritual realization) then as a matter of austerity the person enters into a state of religious or devotional transcendence through meditation and shuts himself or herself off from the world. In that way, the person gives up the body. This is substantially different from euthanasia because the person has not taken any artificial substances to cut out the pain, nor has the person in any way violated the laws of the nature.

Fasting is considered to be a sacred activity. Generally, people fast for a day or so, e.g. on ekadashi and many other important tithis, but there are people who will fast longer. The purpose of fasting is not to torture the body but when the body is no longer capable of functioning then there is no point in prolonging the body. There was an ISKCON sannyasi, His Holiness Narmada Maharaj, who was suffering from Parkinson’s disease which made it impossible for him to do any service. When he decided to do prayavrata, many devotees tried and encouraged him to eat food but he gave a very devotional reply (shows that although his body was out of control but his consciousness was fairly controlled). He said that my body is meant to serve Krishna but if my body cannot serve Krishna then there is no reason to maintain this body? Here is a clear understanding that we are not our body and the body is just a tool for serving Krishna. If the tool cannot serve that purpose, then what is the need to maintain that tool. This should not be mistaken as an escape consciousness, it is actually transcendental consciousness. Very few people can have this kind of consciousness.

In general, euthanasia is strongly discouraged. Instead the person should be encouraged to try and absorb his mind in Krishna so that not only he gets relief from the pain by absorption in Krishna but can also get purification. There is a story on this website (How my cancer became a blessing) about one female devotee, Surapriya Mataji, which shows that how absorption in Krishna can provide relief from the pain at the time of death.

Shortly speaking, she had breast cancer which spread through her bones and she wanted to have euthanasia administered but her sons who were devotees were against it. They told her not to do it and asked her to absorb herself in Krishna and she took that advice to her heart which changed her life. She lived an exemplary life for the last six-seven months. The point is, certainly we do not want to be hard hearted and sentence pain to people who are suffering but at the same time, we have to understand that sentimental or quick fix solutions to avoid sufferings may end up in making the sufferings worse. Whereas courageously facing sufferings and transcending those by absorbing in Krishna can offer much greater salve to the person.

End of transcription.

The post What is the Vedic perspective on euthanasia? appeared first on The Spiritual Scientist.

From Entangled to Enlightened – Lessons from Yayati story

→ The Spiritual Scientist

[University Talk at Singapore]

Podcast

Podcast Summary

Video:

The post From Entangled to Enlightened – Lessons from Yayati story appeared first on The Spiritual Scientist.

‘King of Braj’ – Krishna Reggae for Children’s Rights

→ ISKCON News

Radha Rasesvara Anniversary

→ Ramai Swami

HH Haladhar Swami and I were guests at the twentieth anniversary of the installation of Sri Radha Rasesvara, Sri Jagannatha, Baladeva, Subhadra and Sri Gaura Nitai at the temple in Bali.

When I first came here there were no temples and very few devotees. Programs were held in devotee homes. Now we have five main temples and a number of smaller preaching centres. This all due to the mercy of the Lord, Srila Prabhupada and his enthusiastic devotees here.

The evening went nicely with abhiseka, speeches, kirtan, dances and drama. This was held in the basement of the new temple that is being built. At the end the devotees greeted Their Lordships in the old temple room and had wonderful prasadam.

Sun Love Feast – Dec 1st 2019 – Vedic discourse by His Grace Aindra Prabhu

→ ISKCON Brampton

| |||||

Vedic Contributions in Ancient Europe, By Stephen Knapp

→ Stephen Knapp

We know that the ancient Vedic culture had spread or had influence throughout many parts of the world. Evidence can show this, if we know what to look for and do the right research. So this article will show a little of that evidence.

Starting with Greece, which is often considered the cradle of Western civilization, Greece was originally of the name Hellas, and the land of Hellas was so called from the magnificent range of heights situated in Baluchistan, styled by the name “Hella” mountains. So where did the name Greece come from? The word itself signifies the Indian origin of the ancient Greeks. The royal Indian city of Magadha was called Rajagruhi [now Rajgir] during the Mahabharata times, and people of Magadha were known as Gruhiks. After the defeat of Jarasandha by Sri Krishna, the Gruhikas moved through northwest India and into the area of Greece. These people named their new country as Gruhikadesh, which then changed to Graihakos and to Graikos to Graceus and finally to Greece. In the same way, the name of Macedonia came from the name Magadhanian, indicating an extension of Magadha in ancient India. (Shah, Niranjan, Greece–A Colony of Ancient India, India Tribune, July 30, 2005.)

In this way, much of the advancement that was experienced in Greece was because of the influence, especially in mathematics, literature, and other fields, from ancient India. As the French author Louis Revel writes in his book The Fragrance of India (Les Routes Ardentes De L’Inde): “If the Greek culture has influenced Western civilization, we must not forget that ancient Greeks themselves were also sons of Hindu (Indian) thoughts.”

Jawaharlal Nehru also wrote about the Vedic influence of the Upanishads on early Greece and Christianity: “Early Indian thought penetrated to Greece, through Iran, and influenced some thinkers and philosophers there. Much later, Plotinus came to the east to study Iranian and Indian philosophy and was especially influenced by the mystic element in the Upanishads. From Plotinus many of these ideas are said to have gone to St. Augustine, and through him influenced the Christianity of the day… The rediscovery by Europe, during the past century and a half, of Indian philosophy created a powerful impression on European philosophers and thinkers.” (Nehru, Jawaharlal, Discovery of India, The Signet Press, 1946, p.92.)

Poets in Greece tried their best to create literature similar to that of India. In fact, German scholar Barren Van Nooten, who translated the Rig Veda, wrote in the Introduction to Philosophy of Hinduism: An Introduction to Philosophy of Hinduism by T. C. Galav: “There are virtual copies of plots, characters, episodes, situations, and time duration from the Mahabharata in Homer and Virgil.”

Then we have another Greek ruler, Agathocles, who not only used the Vedic emblems of Krishna and Balarama on his coins, but took pride in calling himself a Hinduja, an Indian by birth. In India we also have the example of Heliodoros, a native of Taxila and a convert to Vaishnavism, who came to India as an ambassador of the Greek king Antialcidas, to the court of the Shunga ruler Bhagabhadra and erected his Heliodorus column at Vidisha, which announced his dedication to the worship of Vishnu.

This Heliodorus column provides undeniable archeological evidence that the Greeks were impressed with the Vedic culture as far back as 200 BCE. This Heliodorus column was erected by the Greek ambassador to India in 113 B.C. at Besnagar in central India. The inscription on the column, as published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, says:

This Garuda column of Vasudeva (Vishnu), the god of gods, was erected here by Heliodorus, a worshiper of Vishnu, the son of Dion, and an inhabitant of Taxila, who came as Greek ambassador from the Great King Antialkidas to King Kasiputra Bhagabhadra, the Savior, then reigning prosperously in the fourteenth year of his kingship. Three important precepts when practiced lead to heaven: self-restraint, charity, conscientiousness.

This shows that Heliodorus had become a worshiper of Vishnu and was well versed in the texts and ways pertaining to this spiritual path. It can only be guessed how many other Greeks became converted to Vaishnava Hinduism if such a notable ambassador did. This conclusively shows the Greek appreciation for India and its philosophy, and that it antedated Christianity by at least 200 years. This disproved claims of the Christians and British that the stories of Krishna in the Puranas were modern and merely taken as adaptations from the stories of Jesus, or that the Vedics were influenced by and adopted any of the philosophy of Christianity before this time.

Now going to Germany, we can see a Vedic connection starting with the very name of Germany. It is explained that the word German came from the name of sharma or sharman, which is an Indian name. Thus, Germany was a country connected with Vedic tradition from many years ago. It is also interesting that the German Sanskritist Max Muller described himself on the front page of his translation of the Rig Veda as, “By me, born in Sharman country, resident of Oxford, named Max Muller.” This would also lend credence that Germany was once known as Sharman-desh, or the place of the Sharmans, a brahminical class of people, connected with the Vedic culture. So you could say that Germany should have been called Sharmany.

This connection may also be why there have been a number of scholars who were fascinated by and studied Sanskrit. These included people like August Wilhelm Schlegal, Immanual Kant, Jacobi, Arthur Schopenhaur, Paul Dressen, Richard Wagner, Frederich Nietzsche, and others.

In Ireland, we can see a lot of the Vedic influence, starting simply with its name. In Historic India, published by Time-Life Books, we read on page 39 that, “In Celtic the word (Arya or Aryan) was transformed into ‘Erin’ which in English became Ireland.” So there is a direct connection between what became Ireland and its heritage from the Vedic Aryan culture.

In Reverend Faber’s book Origin of Pagan Idols, he feels the same way when he says: “The religion of the celts, as professed in Gaul [France] and Britain is palpably the same as that of the Hindoos and Egyptians.” (Faber, Origin of Pagan Idols, B. IV, Ch. V, p. 380.)

The Celts were also one of the first civilizations north of the Alps recorded in history. By the third century BCE they existed from Ireland to central Turkey, through Italy, to southern Spain and north to Belgium.

The patriarch of their good gods was Nuada, born of Goddess Danu. Danu was also called Anu or Ana, and was like the universal mother. All the other gods are like her children. Goddess Danu is said to have ruled over Ireland some 4000 years ago. Patricia Monaghan writes in her book, The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology, that there was an Irish divine race that represented the God of the Celts, named Tuatha De Danann, the people of Goddess Danu.

We also find Danu prominently in the Vedic tradition. It was the clan of Danavas that came from Danu. The Vedic Danu was one of the thirteen daughters of Prajapati Daksha, and was married to Kashyapa Muni. In the Irish tradition the father of Danu is called Dagda, very similar to Daksha. Being the daughter of Daksha also means that she was the sister of Sati, the wife of Lord Shiva. The Celtic Nuada was also called Argetlam, or “He of the Silver Hand.” He was their war god, or like the Gaelic Zeus, or Jupiter. Nuada’s consorts were war-like goddesses called “Hateful,” “Venomous,” “Furry,” “Great Queen,” and others. This was similar to Shiva and the different forms of Devi, such as Amba, Bhavani, Kali, Parvati, etc. Other Celtic gods included Teutates, Taranis, and Esus.

Kashyapa had two wives from whom come lineages that were noted in the Vedic culture. From Danu came the lineage of the Danavas. Another lineage was from his wife Diti, who gave birth to the Daityas. Germany was previously called Daityastan, from which came the name Deutchland. Stan is Sanskrit meaning land, so Daityastan merely means the land of the Daityas, the sons of Diti. So we can see the closeness of this with the Vedic tradition.

Similar to the Celts, the Scandinavians also recall coming from an area to the southeast from many years earlier. The Sanskrit chants of the Vedas also are connected with the Eddas of Scandinavia. In fact, as Christianity took over the area, the word Veda became mispronounced as Edda. That is the only explanation as to why elephants are mentioned in the Eddas and traditions of Scandinavia, although they do not exist there.

A small comparison can be made when we read in the Eddas about the process of creation, wherein it says: “There was in times of old, not sand, not sea, not waves, Earth existed not. Not heaven above, it was a chaotic chasm, and grass nowhere. The Supreme ineffable spirit willed, and a formless chaotic matter was formed.” However, this is also very similar to statements about the universal creation in the Brahmanda Purana and others from the Vedic tradition.

These are just short snippets of evidence. Anyone who would like more information about this topic can find it in the books of Stephen Knapp, namely his latest, “Mysteries of the Ancient Vedic Empire,” and his previous book “Proof of Vedic Culture’s Global Existence,” or visit his website at: www.stephen-knapp.com.

Gratitude for God’s Gifts

Giriraj Swami

If we are at all aware of how dependent we are on God—for the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, and our very ability to eat and drink and breathe, to think and feel and will, and to walk, talk, and sense—we will feel grateful and want to reciprocate God’s kindness. We will want to do something for He (or She or They) who has done, and continues to do, so much for us.

If we are at all aware of how dependent we are on God—for the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat, and our very ability to eat and drink and breathe, to think and feel and will, and to walk, talk, and sense—we will feel grateful and want to reciprocate God’s kindness. We will want to do something for He (or She or They) who has done, and continues to do, so much for us.

We often take things for granted until we lose them. I use my right hand to chant on meditation beads, and one morning I found that I had severe pain in my hand and could no longer use it for chanting. I had taken the use of my hand for granted, but when I lost its use, I resolved to never take it for granted again and to always use it in the best way in God’s service.

How can we attempt to return some of God’s favor, some of God’s care and love for us? My spiritual master, Srila Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, gave one answer:

“Whatever you have got by pious or impious activities, you cannot change. But you can change your position, by Krishna consciousness. That you can change. Other things you cannot change. If you are white, you cannot become black, or if you are black, you cannot become white. That is not possible. But you can become a first-class Krishna conscious person. Whether you are black or white, it doesn’t matter. This is Krishna consciousness. Therefore our endeavor should be how to become Krishna conscious. Other things we cannot change. This is not possible.

tasyaiva hetoh prayateta kovido

na labhyate yad bhramatam upary adhah

tal labhyate duhkhavad anyatah sukham

kalena sarvatra gabhira-ramhasa

[Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.5.18]

Kalena, by time, you will get whatever you are destined. Don’t bother about so-called economic development. So far as food is concerned, Krishna is supplying. Eko bahunam yo vidadhati kaman. He is supplying even cats and dogs and ants. Why not you? There is no need of bothering Krishna, ‘God, give us our daily bread.’ He will give you. Don’t bother. Try to become very faithful servant of God. ‘Oh, God has given me so many things. So let me give my energy to serve Krishna.’ This is required. This is Krishna consciousness. ‘I have taken so much, life after life, from Krishna. Now let me dedicate this life to Krishna.’ This is Krishna consciousness. ‘I will not let this life go uselessly like cats and dogs. Let me utilize it for Krishna consciousness.’”

I pray that I will dedicate this life and everything I have—everything God has given me—fully in God’s service, following His pure devotees.

manasa, deho, geho, yo kichu mora

arpilun tuya pade, nanda-kisora

“Mind, body, and home, whatever may be mine, I surrender at Your lotus feet, O youthful son of Nanda!” (Bhaktivinoda Thakura, Saranagati)

Yours in service,

Giriraj Swami

Does the Lord Deliver Personally?

Giriraj Swami

In his talk on the Bhagavad-gita 9.20–22, on December 7, 1966, in New York, Srila Prabhupada stated:

In his talk on the Bhagavad-gita 9.20–22, on December 7, 1966, in New York, Srila Prabhupada stated:

“The Lord says a very nice thing. What is that?

ananyas cintayanto mam

ye janah paryupasate

tesam nityabhiyuktanam

yoga-ksemam vahamy aham

[Gita 9.22]

[‘But those who worship Me with exclusive devotion, meditating on My transcendental form—to them I carry what they lack and preserve what they have.”] Here the Lord gives assurance that ‘Those who are unflinching and cent percent devoted in the transcendental service of Me, for them I take charge of their maintenance, all comforts.’ Nityabhiyuktanam yoga-ksemam vahamy aham.

“Now, this sloka is very important for devotees. There was a great devotee named Arjunacharya. When he was writing commentaries on this particular sloka, verse, he saw tesam nityabhiyuktanam yoga-ksemam vahamy aham, that the Lord says, ‘I Myself take the burden and take the load on My head, and I deliver to My devotees what they require. They don’t require to go outside. I Myself go and deliver the goods, whatever they require.’

“This is written here. Tesam nityabhiyuktanam. Those who are cent percent engaged in the loving service of the Lord, tesam nityabhiyuktanam yoga-ksemam vahamy aham. Yoga means what is required by him, and ksemam means what he has got, what he requires to be protected. So, these two things the Lord takes charge, that ‘I personally do it.’ For whom? Ananyas cintayanto mam: those who have no thought other than Krishna, who are Krishna conscious. Ananyas cintayanto mam. Ye janah paryupasate—engaged in that way always. He has no other business, simply Krishna. The Lord does these things for him. It is specifically mentioned here.

“This is an encouragement. This is an encouragement by the Lord that ‘Do not think that because you are not trying for going to the other planet you will be unhappy. You will have happiness.’ What is happiness? Happiness is within your mind. If you are assured of your peaceful existence and the next life you are transferred to the supreme planet, or supreme place, then that is happiness—not for trying life after life to adjust happiness. Here is an assurance.

“This Arjunacharya . . . That’s a very nice story. When he was writing commentaries, and he thought, ‘How is that, the Lord will come Himself and deliver the goods? Oh, it is not possible. He might be sending through some agents.’ So he wanted to cut vahamy aham, ‘I bear the burden and deliver.’ He wrote in a way that ‘I send some agent who delivers.’

“Then Arjunacharya went to take bath, and in the meantime two very beautiful boys brought some very nice foodstuffs in large quantity. In India there is a process of taking two sides burden on the bamboo; just like a scale it is balanced. So, these two boys brought some very highly valuable foodstuff and grains and ghee and the like, and his wife was there. And the boys said, ‘My dear mother, Arjunacharya has sent these goods to you. Please take delivery.’ She said, ‘Oh, You are such nice boys, You are such beautiful boys, and he has given You? Acharya is not so cruel. How is that? He has given so much burden to You, and he is not kind?’ ‘Oh, I was not taking; just see, he has beaten Me. Here is the cane mark. Just see.’ His wife became very much astonished, that ‘Acharya is not so cruel. How he has become so cruel?’ She was thinking in that way.

“Then she said, ‘All right, my dear boys. You come on,’ and gave Them shelter. And, ‘No. We shall go, because when Arjunacharya comes back, he will chastise Us.’ ‘No, no. You sit down, take foodstuff.’ She prepared foodstuff, and then They went away.

“When Arjunacharya came back, he saw that his wife was eating. It is the system of Indian families that after the husband has taken food, the wife will take. They don’t take together. After the family members—the boys and the husband—are sumptuously fed, then the housewife takes.

“So Arjunacharya said, ‘You are . . .’ So, the wife said, ‘Acharya, you have become so much cruel nowadays?’ ‘Oh, what is that?’ ‘Now, two very nice boys brought so much foodstuff. You loaded on Their head, and They denied to take it, and you have beaten Them, chastised?’ He said, ‘No, I have never done this. Why shall I do it?’ Then she described, ‘Oh, such a nice, beautiful boy.’

“Then Arjunacharya understood that ‘Because I wanted that God does not deliver personally, so He has delivered these goods, and because I cut these alphabets that He does not give personally, so He has shown that beating mark, cut mark.’ . . . Of course, you may believe or not believe. That’s a different thing. But here the Lord says, ‘I personally deliver.’

“So, those who are in Krishna consciousness, who are actually busy in the matter of discharging their duties as Krishna conscious persons, may be assured that so far their living condition is concerned or their comforts of life is concerned, that is assured by the Lord. There will be no hampering.

“Thank you very much.”

Hare Krishna.

Yours in service,

Giriraj Swami

Should we just accept destiny or keep trying till we succeed?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

Answer Podcast

The post Should we just accept destiny or keep trying till we succeed? appeared first on The Spiritual Scientist.

Sunday, November 24th, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

Saturday, November 23rd, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

Friday, November 22nd, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

Thursday, November 21st, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

Wednesday, November 20th, 2019

→ The Walking Monk

How can we balance body, mind and consciousness?

→ The Spiritual Scientist

Answer Podcast

Transcription :

Transcriber: Sharan Shetty

Edited by: Keshavgopal Das

Question: How can we balance body, mind and consciousness?

Answer: The working of body, mind and consciousness can be understood with the example of a computer system where the body is like the hardware, the mind is like the software and the consciousness is like the user.

In recent times, science has advanced enormously in terms of improving the hardware. At the physical level, today we have comforts like air conditioning, air transport, mobile communication etc. which were unimaginable even for the royalties a few hundred years ago. But unfortunately, to the extent we progressed at the physical level, we also regressed at the mental level. We have far more mental health problems today than we had a few decades ago, what to say about centuries ago. The hardware is improving but the software is getting corrupted by viruses.

If someone throws away their mobile phone not because it is physically damaged but there are too many viruses, we may call such a person a fool. But we see that there are people who just throw away their precious lives by committing suicides due to mental insecurities inspite of having lavish material luxuries.

We are quite careful at taking care of our physical needs (eat wisely, take adequate rest etc.) but at the mental level we have to see what kind of inputs we are giving. Just like, the kind of food we eat determines the shape and structure of our body, similarly the kind of stimuli we take from the world, determines the condition of our mind. The mind is like the palm of the hand and the five knowledge acquiring senses (eyes, ears, nose, tongue and skin) are like the five fingers through which we take information of the outer world.

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of stimuli that we take in – temptation and tribulation. When we get too many temptations (to buy things, touch them, taste them, watch them) then the mind becomes overburdened with desires and those desires make us dysfunctional. We do one thing but crave for something else.

Similarly, we also get a lot of negativity. Life has always been tough but in today’s interconnected world the way breaking news is shared, it is as if things are breaking down everywhere. Continuous exposure to this type of media bombardment stuffs too much negativity inside our minds. That is why we need to regulate what we take-in at the level of the mind which will help our mind become more efficient and effective. Our mind then becomes less of an enemy and more of a friend.

Beyond that, the consciousness needs a spiritual connection with a higher reality and that is where spirituality comes in. Balancing all of these means there is proportionate growth in all aspects. All of us were at one point in our mother’s womb as a tiny single cell but now there are millions of cells in our body, all this happened because of growth. Growth is natural but there is one kind of growth which is destructive and disproportionate, that is cancer. When this happens, it is dangerous and hence we have to make sure that there is a proportionate growth in all aspects of our body-mind-soul. If there is a disconnection and someone practices spirituality which is completely disconnected with the rest of reality, then such type of spirituality is more of an escapism rather than spiritual growth. Hence, it is important that there is balance and proportional growth in all the three where we are growing physically, mentally and spiritually. That is primarily done through association. If we are associating with those who are earnestly pursuing the spiritual journey then observing them and asking questions will help us learn how to balance the three.

End of transcription.

The post How can we balance body, mind and consciousness? appeared first on The Spiritual Scientist.

Moments in a Mini World

→ TKG Academy

Jagannatha Gauranga Temple

→ Ramai Swami

I regularly visit Indonesia, as I am one of the GBCs for the area, and it is always nice to have the darshana of Their Lordships in the various temples. I am fortunate to have the association of many devotees here, who are spread throughout the country.

I visited the Jagannatha Gauranga temple recently, where I led kirtan and gave class. As usual, the devotees were chanting, dancing and listening to the class enthusiastically. On this particular occasion, there was a special ceremony for the passing of Padma and Samudra prabhu’s sister. Everyone gave their blessings for her spiritual advancement in Krsna’s service.

Purchase Gifts for Family and Friends at the TOVP Online Gift Store

- TOVP.org

On Gaura Purnima 2019 we officially opened the TOVP International online gift store to provide usable and popular items with TOVP artwork, graphics, photos and logos. The purpose is to remind ISKCON devotees and congregation about this historic and monumental project, as well as create a small stream of income.

Since its humble beginning we have provided many devotees around the world with our products and want to encourage everyone to take advantage of this unique service. The ‘store’ is online and functions through the Zazzle.com on-demand gift website which creates products one-at-a-time according to your order and ships it to you. Items are also customizable by the buyer so the variety is endless. Through 17 worldwide production centers they ship Internationally based on your location.

Now for the best part, what kind of items does the store have? We have over 1,000 attractive, practical and popular items available in the following Categories of products:

Mens, Womens and Kids shirts and hoodies

Assorted Hats

Travel, Tote, Utility and Handbags

Jewelry and Keepsake Boxes

Clocks and Watches

Necklaces, Earrings and Bracelets

Keychains and Charms

Buttons and Magnets

Photos, Posters and Canvas Prints

Phone Cases and Wallets

Journals, Planners and Notebooks

Mousepads and Thumb Drives

So, if you plan to do any shopping for devotee loved ones and friends, especially during the Holiday season, birthdays, weddings, etc., make the TOVP online gift store your first stop. The link below will direct you to the TOVP Gift Store page on the TOVP website for specific directions and the store links for your country.

https://tovp.org/tovp-gift-store/

The post Purchase Gifts for Family and Friends at the TOVP Online Gift Store appeared first on Temple of the Vedic Planetarium.

A Transcendental Visit

Giriraj Swami

Hridayananda das Goswami stayed with me in Carpinteria over the weekend, and we had many enlivening and enlightening conversations. I could really appreciate Srila Prabhupada’s statement that Maharaja has a “transcendental brain.” He is intent on serving Srila Prabhupada’s mission, especially in America, and our common interest is to please Srila Prabhupada and become Krishna conscious—by his divine grace.

Hridayananda das Goswami stayed with me in Carpinteria over the weekend, and we had many enlivening and enlightening conversations. I could really appreciate Srila Prabhupada’s statement that Maharaja has a “transcendental brain.” He is intent on serving Srila Prabhupada’s mission, especially in America, and our common interest is to please Srila Prabhupada and become Krishna conscious—by his divine grace.

I pray for the association of Srila Prabhupada’s sincere, committed, and affectionate followers, such as Hridayananda das Goswami Maharaja.

Hare Krishna.

Yours in service,

Giriraj Swami

Lecture – Lord Rama’s App. Day LA

→ Prahladananda Swami

Lecture – Lord Rama’s App. Day LA 2015-03-28 #externalpastimes

ADVENT OF BHAGAVAD-GITA (GITA JAYANTI) – DECEMBER 7TH, 2019

→ The Toronto Hare Krishna Temple!

Over five thousand years ago, Krishna spoke the Bhagavad-gita to Arjuna, discussing the fundamental principles of life. The Gita lucidly explains the nature of consciousness, the self and the universe. It contains both the essence of India's spiritual wisdom and the answers to questions that have been posed by philosophers for centuries.

Over five thousand years ago, Krishna spoke the Bhagavad-gita to Arjuna, discussing the fundamental principles of life. The Gita lucidly explains the nature of consciousness, the self and the universe. It contains both the essence of India's spiritual wisdom and the answers to questions that have been posed by philosophers for centuries.Today, that same Bhagavad-gita has been translated to numerous languages and is read by millions of people around the world, revered in academic circles, and studied by spiritualists all over the world.

Saturday, December 7th, 2019 marks Gita Jayanti, the day when Lord Krishna spoke the Bhagavad-gita to Arjuna. Festivities will begin at 5:00pm and will include the recitation of the whole Bhagavad-gita followed by a sumptuous feast. Please join us on this most auspicious occasion with your whole family!

The Glories of Srimad-Bhagavatam

Giriraj Swami

Last night I finished hearing Radhika Ramana dasa’s wonderful seminar on “The Glories of Srimad-Bhagavatam,” delivered at ISV in September 2015. I highly recommend it to all devotees.

Last night I finished hearing Radhika Ramana dasa’s wonderful seminar on “The Glories of Srimad-Bhagavatam,” delivered at ISV in September 2015. I highly recommend it to all devotees.

dharmah projjhita-kaitavo ’tra paramo nirmatsaranam satam

vedyam vastavam atra vastu sivadam tapa-trayonmulanam

srimad-bhagavate maha-muni-krte kim va parair isvarah

sadyo hrdy avarudhyate ’tra krtibhih susrusubhis tat-ksanat

“Completely rejecting all religious activities which are materially motivated, this Bhagavata Purana propounds the highest truth, which is understandable by those devotees who are fully pure in heart. The highest truth is reality distinguished from illusion for the welfare of all. Such truth uproots the threefold miseries. This beautiful Bhagavatam, compiled by the great sage Vyasadeva [in his maturity], is sufficient in itself for God realization. What is the need of any other scripture? As soon as one attentively and submissively hears the message of the Bhagavatam, by this culture of knowledge the Supreme Lord is established within his heart.” (SB 1.1.2)

nigama-kalpa-taror galitam phalam

suka-mukhad amrta-drava-samyutam

pibata bhagavatam rasam a-layam

muhur aho rasika bhuvi bhavukah

“O expert and thoughtful men, relish Srimad-Bhagavatam, the mature fruit of the desire tree of Vedic literatures. It emanated from the lips of Sri Sukadeva Gosvami. Therefore this fruit has become even more tasteful, although its nectarean juice was already relishable for all, including liberated souls.” (SB 1.1.3)

krsne sva-dhamopagate

dharma-jnanadibhih saha

kalau nasta-drsam esa

puranarko ’dhunoditah

“This Bhagavata Purana is as brilliant as the sun, and it has arisen just after the departure of Lord Krsna to His own abode, accompanied by religion, knowledge, etc. Persons who have lost their vision due to the dense darkness of ignorance in the Age of Kali shall get light from this Purana.” (SB 1.3.43)

After hearing Radhika Ramana Prabhu’s seminar, my appreciation for the great gift of Srimad-Bhagavatam and my desire to absorb myself in it have increased dramatically. Here are the links: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JREYpBib_nc and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ua_mH5j9gk.

Hare Krishna.

Yours in service,

Giriraj Swami

Moksada Ekadasi

Moksada Ekadasi